Interactive re-futuring

Keith Gallasch talks to Keith Armstrong

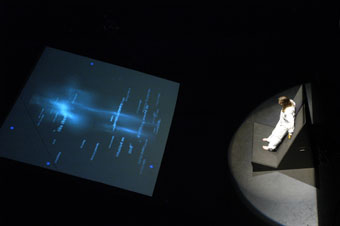

Intimate Transactions, 2003

photo Sonja de Sterke

Intimate Transactions, 2003

Interdisciplinary artist Keith Armstrong has been building a body of impressive work in new media arts over the past decade. This has been largely in collaboration with performer Lisa O’Neill and other members of his Transmute Collective. Armstrong’s attention in new media installations and performance is on the performativity of the artist but also of the audience member as interactor or participant. Currently a post-doctoral new media fellow at the Creative Industries Research and Application Centre, QUT (Queensland University of Technology), Armstrong is critical of new media art where the purpose of interactivity is either unfocussed or pointlessly literal and he is committed to thinking beyond technology to situate his work in an ecology of survival.

Armstrong came from England 14 years ago with a Masters Degree in Electronic Engineering and Information Technology, backpacked around and became an Australian citizen. He’d always dreamed of being an artist, did a TAFE course in Fine Art and Design to get a folio up, a visual arts degree at QUT and later a PhD (“Towards an Ecosophical Praxis of New-Media Space Design”).

I decided right from the beginning that I would call myself an artist and I would canvas for work. So I just started to do it in earnest and I worked very hard. I never stopped working. And I would like to acknowledge QUT as having supported mostly everything I’ve done in the last decade in terms of equipment, resources, people and time. With this sort of work, the number of people you need and the technology is not easy to sustain without a generous benefactor.

What is central to your work?

I’m very interested in performance and in the performing body. I suppose it’s what marks my work as somewhat different from many other new media practitioners. I started as a performance artist, then worked with interactive technology and really have incorporated ideas of performance in almost everything that we’ve done since. I’m very interested in how people like Lisa O’Neill or Tess De Quincey, who we worked with recently, have a strong understanding of the body. I’m very engaged in how that knowledge can be used as a means for the choreographing and navigation of virtual space and what we can understand about interactivity from it. I’ve just instigated a project, an arts/science collaboration, working with a human movement scientist, a ‘tangible interface’ designer and performers to actually look in much more depth at new ways of interfacing.

Beyond new media

I’ve always been extremely engaged with ideas of ecology, particularly ecological philosophies and an understanding of the self in dialogue with the world. Ultimately that’s what drives me. It’s not new media really. It’s not even performance. It’s the discussion of those ideas which I see as central to survival. Tony Fry calls humanity “a de-futuring force” (New Design Philosophy: An Introduction To Defuturing, UNSW Press, 1999). We’re taking away our future day by day and he asks how we might be able to re-future.

How are we de-futuring?

Fry is a design theorist who talks about many of the choices we’re making inadvertently that take away the future. For example, when Henry Ford designed his motor car he didn’t think about how it would re-design the city. As an artist, you do what you can do to add to that conversation and attempt to generate a place for discussion and reflection. One can’t change the world through art but one can tickle people’s imaginations to re-think.

Securing our future means re-thinking our selves and our relationships to others and how we act. Fundamentally, my works are about interconnection, communication and a way of understanding the implications of action and choosing forms that are co-creative and collaborative.

Intimate Transactions

The participant reclines on an abstract form of furniture with embedded sensors, smart materials and computer vision recognition. It becomes a tangible interface device for detecting subtle bodily movements and gestures. These generate responses in the body and text projected on the screen. In its final form participants in different networked locations will simultaneously interact with the work, generating an evolving, flowing combination of ghostly bodies, dynamic texts and spatial sound.

Performer Lisa O’Neill, sound designer Guy Webster and Canberra-based visual artist, sculptor and conceptual furniture designer Zeljko Markov are Keith Armstrong’s key collaborators on Intimate Transactions (for other collaborators and project details go to http://embodiedmedia.com/ ).

Describe the significance of the body action of the participant.

Each of the collaborators came to the body shelf with a different critical perspective. My interest was to generate different types of movements with different kinds of conceptual focii. With my interest in ecological subjectivity I was exploring ideas of things that are close to what I understand as ‘me’ and then moving towards things that appear to be ‘separate from’ or ‘unknown to me’, yet that I understand my body is undivided from. Lisa’s idea as a performer was about a changing state of tension. So she interpreted that idea of the me-zone [as being] very much about tension moving into the stomach area—a key principle of the Suzuki method where stomach tension relates to a strong holding of the floor and a sense of grounding. The next position is to lean out from that centredness.

You really feel like you are leaning out into the void, a black void because it’s in a black theatre with a huge screen sweeping up in front of you. At that point, your hands become part of the interface. It’s very gestural and the energy is moving out. Zeljko Markov, the furniture designer, was interested in creating an object that didn’t have a strong presence but put the body in an unusual position. You’re very stable but as you move out there’s only so far you can actually move. And sonically, Guy interpreted those ideas as sounds that are familiar or sounds that are unknown or hard to pin down. He had a graduated database and the program Max running, spinning in 4 or 5 samples at once, mixing them in real time. It’s impressionistic, but very fluid, very effective.

As you move you’re going through the ‘me’, ‘us’ and ‘other’ zones. If there are 2 scenes side by side and one is the body and one the Calvino text, you can navigate your way through the body, through the text and back around. You’re in a fluid space. It was actually possible to fall off the top and into a holding space. This is something we really want to work on because what we were trying to do was to generate a 2-dimensional abstract map and it’s very difficult to follow when your body’s moving in 3 dimensions. Our new script design will work in 3 dimensions.

You want to network Intimate Transactions rather than it being only an on-the-spot interactive work. Why?

It’s been designed as a multi-locational work, a bit like Jeffrey Shaw’s Web of Life. You can add nodes to the network and a node can log in and off and increase the scope of the work. We’re interested in this idea of presence within a network and what that might mean. We would like people to engage in intimate transactions with other people in other sites whom they don’t know, whom they won’t be able to see or hear—only sense their effect.

It’s not communication or transaction in a direct sense.

A way of seeing it might be as an ecological footprint, the sense of the effect that your actions have in other spaces that you may not consider. Each person will engage with this work within the network—there’ll be physical and online spaces—and they will always be transmitting.

We’ve started to build the idea through a sense of a shared body we’re imagining. We’re now thinking about a thematic of pain. Physical pain is incredibly hard to share in discrete bodies, but if those bodies were shared and we could choose to take on each other’s pain at a certain level, what could that mean, pain flowing through a network of bodies…?

Sounds tortuous.

I’m not interested in actually hurting people, but I don’t think there are many examples of long meditations on pain. Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers comes to mind. Emotional pain is dealt with in just about any artwork you can imagine but physical pain…it’s beyond words.

Re-working

We’re happy with the form of the body shelf but we’re going to change it to a much more bodily sensitive interface. So rather than the hard surface with the small sensoring faces, we think we’ll change the rear body shape to a sprung surface so you can actually match your spine and your body into it. We’re going to drop the hand movements because the whole hand gesturing thing loses meaning. It becomes too much like every other interactive we’ve become frustrated by. It’s really important to me that you ask people to do something which has a meaningfulness in terms of physical response. So we’ve got the back support and we’ve also got a kind of harness system that you move into.

How will you explore the networking?

We’re working towards this for the residency Fiona Winning has asked us to do at Time_Place_Space 3 at AIT Arts in Adelaide. To do anything networked requires a server to handle all the intercommunications. To place more than one person within an environment conceptually requires a whole reorganisation of the script. So that has to be re-thought. And the notion of collaboration within that zone has to be re-thought too. So it’s quite large.

So you’ll need at least 2 of these shelf systems…

Plus an online ability. It feels to me that every project we’ve ever done is always working in a place that we don’t yet quite know how to get to. We always set ourselves challenges which we’re not really sure how to achieve but we do make it. We never seem to go to a safe place.

Testing

The responses to Intimate Transcations were incredibly varied, as you’d imagine. In general everybody found the experience strong, but there were real differences. It was quite daunting, set up in the Powerhouse with small groups and with [an intense] level of vision and sound. Some people were very self-conscious and tense, and froze. Some wanted to control it, to go everywhere and sense a bit of everything. And there were those who were happy just to get on it and start to drift, or to play without attempting to do everything. Those people seemed to have the strongest experiences.

Did you have Lisa there talking to people about how they were using their bodies?

Absolutely. It was very much a team. Lisa, Zeljko, Guy and myself. I talked about the structure of the work, then Lisa and Guy took the participants onto the machine and through the different phases of body shapes that were required. And we were on hand in case they needed us. As much as we could, we let them drift into it.

The performativity you’re interested in is about how people behave on this device?

It’s also about shaping the whole theatrical experience. There was a waiting room as they arrived and a ritual dressing in white suits. There were technical reasons for the suits and the red and yellow gloves in terms of colour recognition for the motion tracking. The system knew where your right and left hands were and the white suit kept the rest of you neutral. But of course, the white suits became a big thing—you know, the space metaphor, biogenetics, the nuclear thing. Not exactly intimate.

What we discovered was that some people found a very strong connection between themselves and the body on the screen. Others felt remote and I believe these were mostly the ones who were looking for control.

How is the onscreen body placed vis a vis the viewer?

The bodies were originally conceived in a blue screen studio with the camera pointing down on Lisa O’Neill performing on a gym horse. She’s on her back performing upwards or on her stomach performing downwards. So the centre of her body never moves…The problem is that people expect an avatar, to see something that represents them because that’s the standard thing. So some people wanted to know if it was them, why wasn’t it always doing what they were doing? We were thinking more of an indirect relationship.

They are shaping the movement of the body and the text but not totally?

Not directly. There is a matrix of computation you’re travelling through, but it’s how you get there. Where you’ve come from and where you’re heading and the velocity at which you’re choosing to move through the system depends on whether you pause and you spend time in an area or you whiz around.

Unlike a video arcade game, a work like this is more analogous to listening to music or looking at a painting. The responses and processes are open-ended.

A sense of agency in interactive work is important—the need to see something of yourself within the interface. But to my mind, if you overdo that you actually lose the power of it.

Lisa O’Neill, Grounded Light

photo Phil Hargreaves

Lisa O’Neill, Grounded Light

Grounded Light

We may say “But we walk on the ground”, yet we should be aware of an ambiguity. For we walk on the ground as we drive on the road: that is, we move over and above the ground. Many layers come between us and the granular earth…Let the ground rise up to resist us, let it prove spongy, porous, rough, irregular—let it assert its native title, its right to maintain its traditional surfaces.

Paul Carter, The Lie of the Land

Grounded Light was a collaboration between myself and O’Neill working with trombonist Ben Marks from the Elision new music ensemble. It was part of Floating Land, a festival convened by Noosa Regional Gallery and directed by Kevin Wilson. This is the second year he’s done it and it’s a 5-year project—very ambitious. This one was a national project and future ones will be international. We worked on a piece on Mount Tinbeerwah, a well-known lookout on the way to Noosa which gives you a 360-degree panorama of the town, lakes and national park. A very nice place to spend time.

We decided to make a work that would take people from the car park to the top of the mountain. A half-hour walk on a moonless night. There were certain places where Lisa stopped and performed. I’d built a costume with controllable lights in it. She carried the sound in her parasol which also had lights. So you’d see this figure in the pitch black, self-lit, moving up the mountain.

At the summit we built an installation of tiny white lights and a video projection on one of the display boards in the lookout. Grounded Light is based around ideas from Paul Carter’s Lie of the Land. He says at one point in his book, “Many layers come between us and the granular earth.” One of the many theses in that work is our inability to touch the land, the Australian landscape. He writes about Colonel Light and Ted Strehlow as characters who were of their time but who were transgressional, who were able to touch the earth conceptually or practically in a different way. So Lisa was dressed in a turn of the century costume as a transgressive character—the grounding of the light was literalised by the lights in her dress that allowed her to press her body down into the landscape. We were making parallels between light and campfires and that different sense of floating and groundedness between the two.

You also see floating lights [on stalks], ungrounded lights, if you like, in the black sea floating round you of Noosa and the hinterland. These completed a net of lights over the mountain. So when you stood in the lookout, you could see them and the lights in the valley and imply a connectivity…a net of human civilisation on the landscape that’s pushing up. Lisa walks through the light field, fading herself out—she had dimmers and switches she could control so she could dissolve into the landscape.

People made their way through the light field and up to the lookout to a display panel of the area. You could point out dots of light: “that’s this mountain; that’s that one.” We also had a crew on Mt Cooroy 3 and a half kilometres away signalling with morse code. Imagine a mountain you can only just see in the darkness and, right at the very top point, a light comes shining out. There was a collective “Aaaah.” Kids loved it. The whole thing had a magical-real feel. And then they saw an animated view of the landscape projected on the display board with quotations from Carter. It was a quiet installation, a wind-down, a 5 minute looping animation with a video projector powered by a solar battery rig.

Is Grounded Light something you’d like to repeat elsewhere?

Absolutely. Although it was a site-specific work it could be re-contextualised relatively easily to a range of other mountains: sites where you’ve got a good view of the city lights below and some sense of a traverse and a place to build an installation.

Grounded Light, Transmute Collective, interdisciplinary artist Keith Armstrong, performer Lisa O’Neill, musician Ben Marks, Esther Cole (QUT design student), production James Muller, Earthbase Productions; Floating Land, presented by Noosa Regional Gallery, Oct 17-18, 2003

Intimate Transactions, Transmute Collective, artistic/visual director Keith Armstrong, performance director Lisa O’Neill, sound Guy Webster, systems designer/programmer Glen Wetherall, electronic sound designer Greg Jenkins, Max programmer/sound system design Benn Woods, 3D Artist Chris Barker, furniture design Zelgko Markov; test showing, Brisbane Powerhouse, August 19-21, 2003

RealTime issue #59 Feb-March 2004 pg. 20-