Interview: Steve Matthews, going seriously solo

Over the last decade a wave of mature aged artists have undertaken creative doctorates which provide opportunities for making new works that will contribute vital research for their artform fields. Well-known Sydney-based acting and leadership teacher Steve Matthews, who took on a Doctor of Creative Arts in the Department of Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Sydney without the support of a scholarship and juggled work and research, is completing his thesis around a deeply personal autobiographical performance made for the doctorate.

Personal solo performances comprised an important strand of contemporary performance and theatre-making in the 1990s and 2000s in Australia, not least from Aboriginal, NESB and female artists whose works had more than personal resonances. For Matthews, these makers have provided inspiration and have helped frame and influence his own work and thesis writing. We met with him to discuss his background in theatre and teaching and his experience of making a demanding personal work and meeting the considerable demands of the academy. He gave us an enjoyably frank and judicious account of the experience and an assessment, which any artist, of whatever age, scholarship or not, should consider before taking on a creative doctorate.

Where and how did you commence your career in theatre?

I started out as an actor in New Zealand in the early 1970s. I left school, there was no drama school and so I went to the local theatre, auditioned and started working professionally at the age of 18 in Wellington and regional theatres in New Zealand for a few years. I went to Wellington’s Victoria University as well, did an Arts degree and then I came across Francis Batten, who had been at the Jacques Lecoq School in France for a couple of years. He had convinced four French graduates to set up a professional company, Theatre Action in New Zealand, which was pretty amazing. I went to one of their workshops, along with Sam Neill, as it turned out. I was invited to join the company and virtually did my training on the job, moving from being a text-based interpretative actor to developing skills in performance-making. After Theatre Action, I set up my own companies and gradually moved into running acting and performance workshops in New Zealand.

I came to Australia at the end of 1988 and I was fortunate; chatting with someone at NIDA, who said, “we need an improvisation teacher.” That’s when I moved more into teaching, taught at the Actors Centre for 15 years, spent 1991-94 at Theatre Nepean, Western Sydney University, and 2004-08 at Charles Sturt University. More recently, as Principal Lecturer, I ran the Performing Arts department at the Adelaide College of the Arts in 2014-16, came back to Sydney and am now teaching at AIM and AFTT as well as doing some executive coaching and leadership development consultancy.

What motivated you to do a creative doctorate?

After 20 or so years of teaching, I was feeling I was doing a lot to facilitate other people’s creativity and I really wanted to do something for myself. The trigger was the death of my father. Ours was not an easy relationship. By the end of his life we had reached a place where it was good, but I was aware that there were aspects that I needed to explore. I had seen and been very inspired by Spalding Gray in the 1980s. I had also worked with Playback Theatre both here and in New Zealand, so the idea of working with personal stories got me really interested.

I’d been working in tertiary education where they keep raising the bar — ‘you need a masters,’ ‘no, you need a doctorate.’ So I was looking at a way of combining something in which I had a strong personal interest as a practitioner with working within a research community and, of course, gaining a qualification. I don’t think I really understood the extent and the depth of the work required both as a practitioner and as an academic.

What was the focus of your research?

It was definitely about creating my own solo performance. There was a big challenge in that. I wanted to work with my own lived experience and my own family story. The second thing was thinking this could be a really interesting practice-led research project. What was critical was finding two former practitioners who are now academics, Glen McGillivray and David Wright. Your supervisors are really key to your success. And it’s been a fantastic journey with them. It’s a challenge as a mature-aged student, becoming a student again when you’re more used to being in the lecturer-director position.

The two parts of the doctorate comprise “a substantial creative project” and a thesis or exegesis. I did the practice part a few years ago. Because I’ve had to do this along with full-time and part-time work — fitting everything else in — it’s taken probably longer than I would have liked to write the thesis. But the process has been good in terms of the challenge and understanding my own history and my own performance modality.

What did that involve?

In a solo autobiographical show you’re talking directly to the audience and dealing with real life experiences. You’re triggering and visualising all that material. I spent three months with a dramaturg. Improvising on the floor with the material was really interesting in terms of accessing and embodying those experiences. Some of it was cathartic. I’d written a scene — about the last time I saw my father — that was challenging to replay, but a necessary part of the process. I only gave the one showing at the university, followed by a Q&A session, but I had to get to a point where I was a bit detached from the material. Not completely, but I didn’t want to be acting out this material and feeling so emotionally vulnerable. Then, when the performance was shaped and crafted, in the end I was working with a script.

Why did you choose this degree at the Department of Performance Studies at the University of Sydney?

I’d started the doctorate at Western Sydney University but the performance school was closed down. It was just circumstance that I could take it up at the University of Sydney as one of my supervisers, Glen, was offered a job with the Department of Performance Studies. The department has a very supportive postgrad culture. There are seminars every Friday during the term. You present your next chapter or a paper, receive feedback and listen to everyone else’s research as well. It’s great.

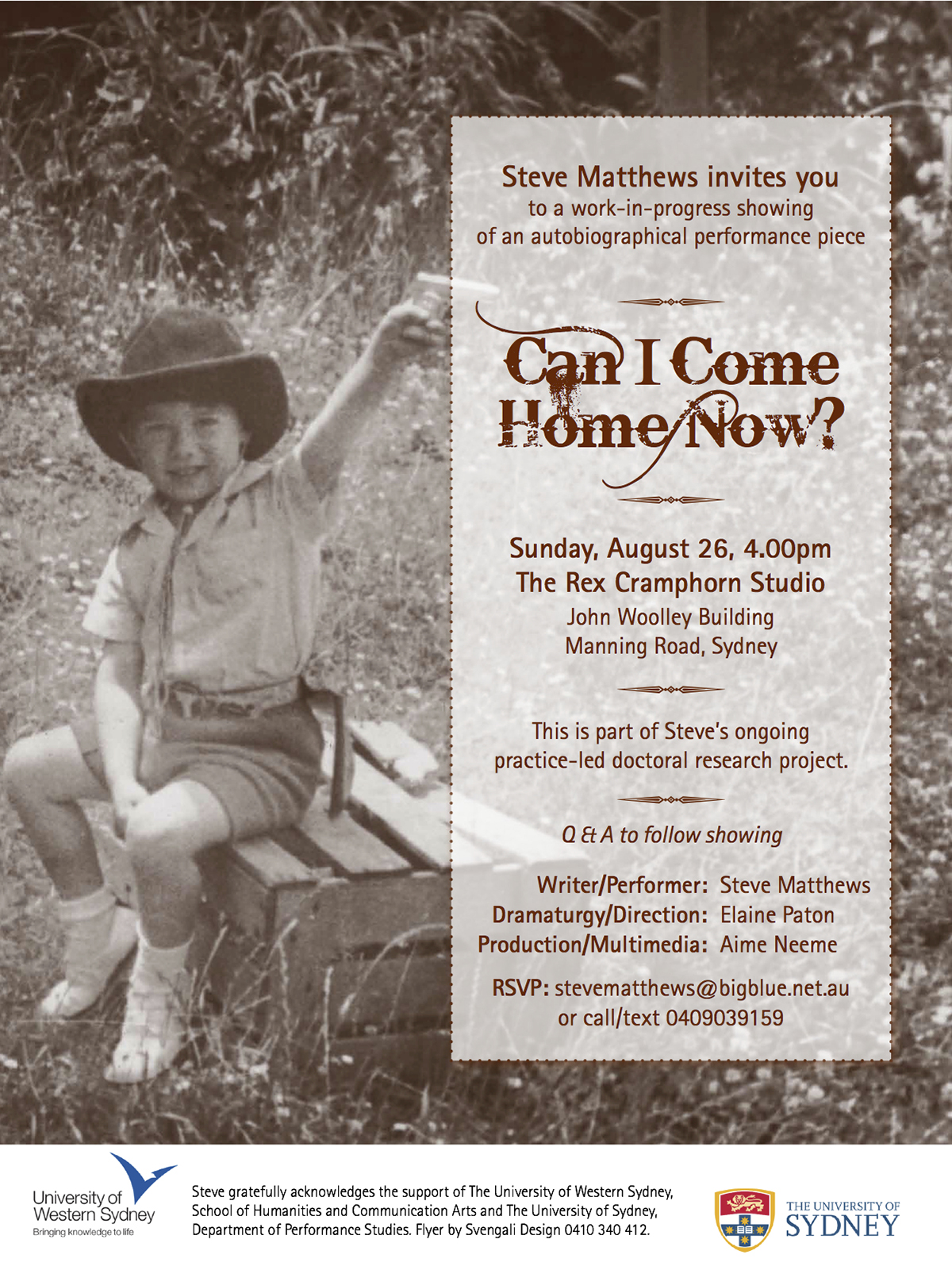

Poster for Steve Matthews’ solo performance

What did your extensive research into Australian autobiographical performance do for you?

Initially I did it because I had no template around how to make a solo autobiographical work. I wanted to be challenged. I wanted to step into an area where I didn’t really know what I was doing. So, firstly, it involved going to see the work of a lot of different practitioners and then interviewing them, which I hadn’t planned to, but it made sense. It was just curiosity really. I attended performances by and interviewed nine solo autobiographical performers: William Yang, Tim Stitz, Meme Thorne, Deborah Leiser-Moore, Paul Capsis, David Page, Paul Dwyer, William Zappa and Michel Workman.

I’d written a book, Getting into the Act (1988), about improvisation, acting and performance-making and I’d been part of theatre companies devising material, but I had not written a play as such. The first thing for me was to understand the process of autobiographical writing. I checked into courses at the NSW Writers Centre and I came across a wonderful teacher, Patti Miller, who specialises in teaching life writing. So I went to one of her courses and this gave me the structure and some techniques for starting to write my own life stories. I also went to courses with the writers Beth Yahp and Jacquie Kent. These helped to give me the discipline and motivation to keep writing my stories. Initially I found myself focusing more on the playful, fun stories of childhood. It took a while to say to myself, ‘Okay, Steve, you’ve got to get into the darker stuff.’ The writing process continued for about three years. I went back home, did an interview with my Mum, got the suitcase full of family photos. Then I had about 80 pages of stuff, which I sent out to colleagues — dramaturgs, writers and a few academics — and said, “Be honest, just tell me what you think.” And they did!

They gave me some really valuable feedback around my writing style and what was working and what wasn’t. I realised that this was now the time to get up on the floor and to start working it. I was fortunate in that a colleague, Elaine Paton, who is a dramaturg and director, had already read some of the stories and had helped me transcribe the interviews, and said, “I really like this project. If you want someone to work with you …” So that’s what we did. We got a space at the University of Sydney, and I got a bit of money to pay her and we worked away. It was very challenging for me because I was still unsure about the material. I hadn’t really been working as an actor for a long time; I’d been working as a director and teacher. It took us a while to find a good working relationship, which we did. But it was an exhausting process. Really demanding.

Was it satisfying to perform the work in the end?

Oh, completely! Totally satisfying. Great feedback from the audience after the show. Always, you need more time. I think, too, it was not only the performing of the work that was demanding. I was writing it, producing it, compiling all the photographs, props, music, doing the marketing, everything. The lesson next time would be to get a bigger budget, delegate, have a longer rehearsal time. Having said that, I had a good production team in Elaine as director and dramaturg, lighting designer Ben Anshaw and multimedia designer Aime Neeme.

Who might your research benefit?

At the end of it I’m definitely in a position to help anyone who wants to do an autobiographical solo show, to workshop and direct it with them. I can now add this to the list of performance workshops I teach. It is so different from a solo show where you’re playing scenes from a scripted play, because of the personal nature of the material and the way to write, craft and perform it is quite different.

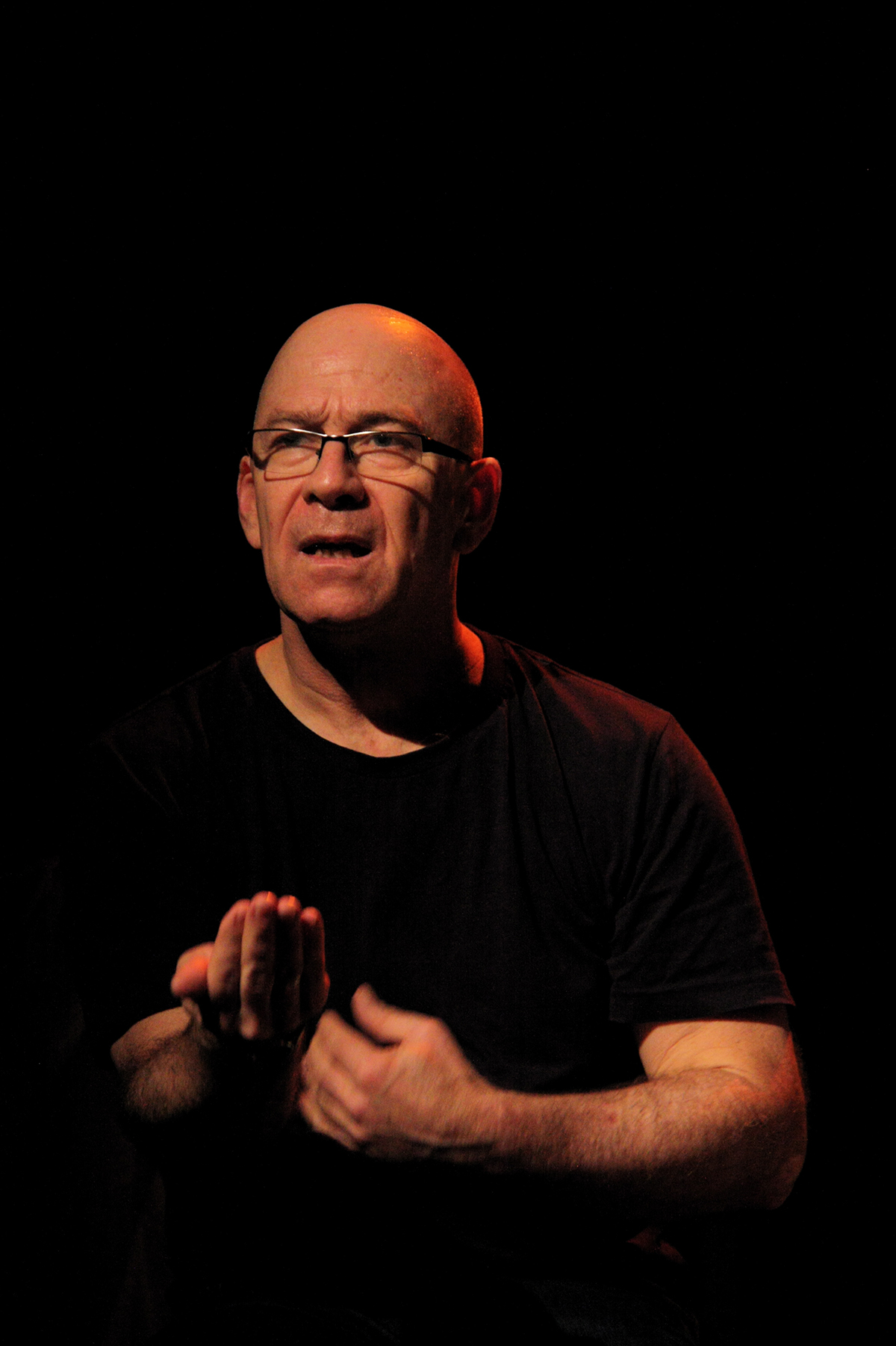

Steve Matthews

How was the doctorate workload?

Creative doctorates are still considered a little bit like the poor cousins of PhDs. It’s almost like you do twice the work — make a professional work and then thoroughly document and reflect on it. My expectation was that it was going to be more about the practice and less about the theorising. I haven’t minded doing it, but it’s been a helluva lot of work. It’s why I think having former practitioners as supervisors makes a big difference. But still I think the expectation is that it’s going to be like any other PhD.

How long was the performance?

90 minutes. I had to go into rigorous physical training — yoga, swimming — so I could sustain the energy required. I don’t regret any of it. It’s been a huge challenge and I’ve really loved it. I’ve had to really step up. It’s meant sacrificing a lot in terms of my personal life and professionally.

When will you complete the thesis?

This year. I’m determined. As well as extensive reflection on my own work there’s a chapter on the Australian performers I interviewed. Then there’s the literature review which looks at the development of this genre of solo autobiographical performance — I’m calling it a ‘genre’ because I think it’s quite specific — and how it developed through contemporary performance in America. Most of the literature is about what happened in America from the 80s onwards, and the UK as well. There isn’t much written about what’s happened here. There’s a book in it, but whether I want to spend another five years of my life writing it… (LAUGHS).

–

Visit Steve Matthews’ website here and the University of Sydney’s Department of Theatre and Performance Studies here.

Top image credit: Steve Matthews, Can I Come Home Now?