Is birdsong music? Ask the butcherbird

Just because it sounds musical, is it music? Composer, musician, ornithologist and Macquarie University research fellow Hollis Taylor argues that birdsong should be classified as music, basing her case on years of studying birdsong, particularly that of the pied butcherbird, cracticus nigrogularis.

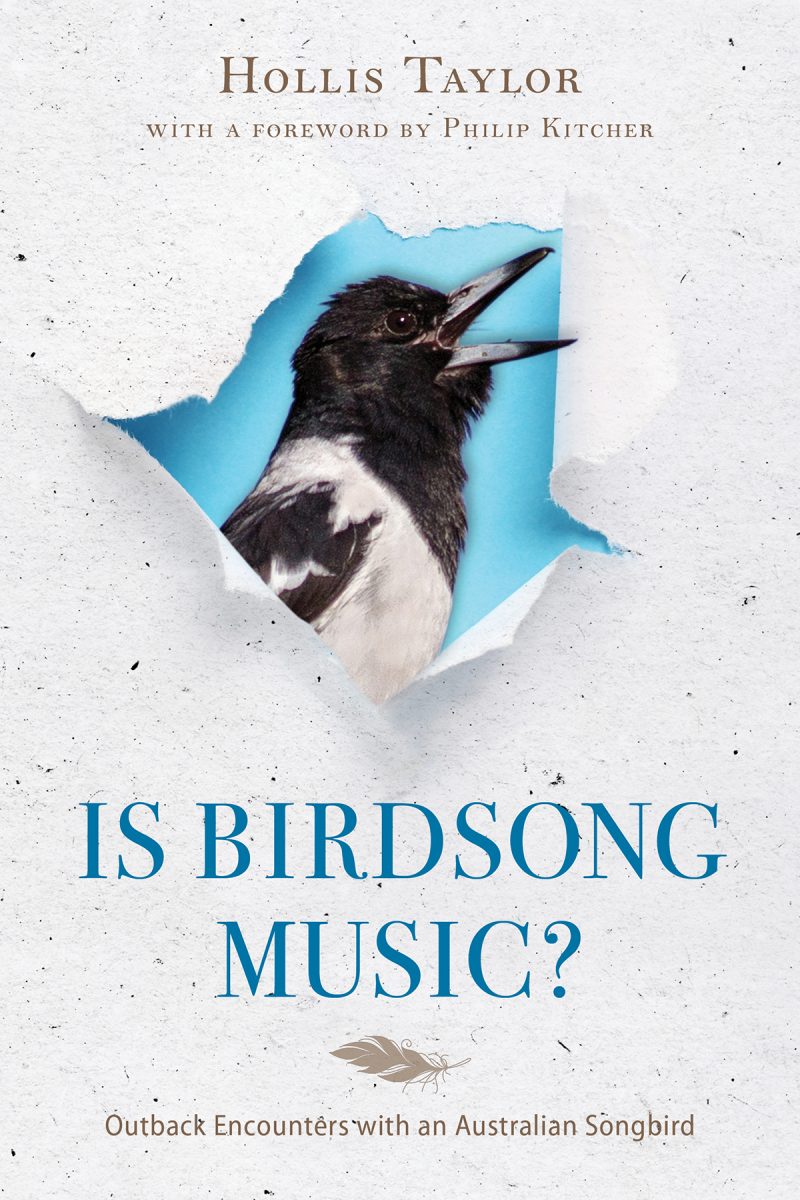

Birdsong has delighted humans throughout history but musicologists typically rule out of consideration anything not made by a human. But Taylor points out that there is no universally agreed definition of music, and thus it is technically impossible to decide whether birdsong constitutes music. Describing herself as a zoömusicologist, Taylor has published a book, Is Birdsong Music? (Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2017) in which she argues persuasively that the concept of music should be broadened to encompass musical sounds made by other species. She has also produced a double CD, Absolute Bird, comprising performances by various musicians, including herself, of her transcriptions and arrangements of pied butcherbird song sourced from her own and other ornithologists’ field recordings. The CD contains detailed notes on the sources of the field recordings and how they have been employed in developing the musical works, and the book and CD are complemented by a web-page that provides samples of her field recordings and photographic records from her field trips. The field recordings are analysed in the book and readers should have the web-page open as they read. Listening, you feel as if you’re in the bush with the birds.

The point Taylor makes is that butcherbird song is not only a form of communication but has an aesthetic character, from which it might be inferred that the birds have an aesthetic sensibility analogous to our own. In her book, she details the difficulties of transcribing butcherbird song and her approach to it, and the invited musicians on the CD, all stars in their own musical fields, perform her transcriptions with great insight and virtuosity. Genevieve Lacey (recorders), Jim Denley (flute), Joanna Cannon (bassoon), Mike Majkowski (bass), Claire Edwardes (vibraphone), Ros Dunlop (bass clarinet), The Song Company (human voice), Errki Veltheim (violin) and Taylor herself (violin) make fabulous music and the musicality is obvious regardless of whether the composers’ (the birds’) intentions were musical in any human sense. The performers’ ability to convey the character of butcherbird song is remarkable, and the broad range of instruments used, often in combination with recorded material, demonstrates the wonderful ways in which butcherbird music can be represented. In some pieces, the mix combines the performer’s playing with field recordings of butcherbirds singing, the vocalisations of other species including cane toads, stories of encounters with butcherbirds, and other local sounds such as a cattle auctioneer and a military helicopter flying overhead. The result is not only engaging musically, it also raises our awareness of the birds’ behaviour and environment. The ultimate work on the double CD is a captivating 14-minute string quartet entitled Bird-Esk, performed by James Cuddeford and the author (violins), Veltheim (viola) and Daniel Yeadon (cello), which is based on the songs of an ensemble of 8-10 pied butcherbirds recorded at Esk, Queensland, in 2008.

By transforming birdsong into music as we usually understand it, as have other composers she acknowledges, such as Olivier Messiaen and Ron Nagorcka, Taylor appears to preempt the answer to the question of whether birdsong should be categorised as music — it sounds musical, therefore it is already music. But her broader concern is with the pied butcherbirds’ capacities and not just with our musical awareness. Her analysis of their song, for example the range of possible sounds they can make and the contexts in which they choose to make them, demonstrates their musical inventiveness. She suggests that, “pied butcherbirds’ artful combinatorics… exceed a rigid set of instructions. Such substantial scope for individual variation in this singing tradition, where repertoire can be pulled out of memory and performed in different circumstances and presumably under different motivational conditions and in different seasons, points to a capacity to manipulate to ‘musical’ effect.”

While aware of the possibility of anthropomorphism in her analysis, Taylor considers the musical character of various kinds of solo songs, duets, mimicry and the species call. She listens for timbre, pitch and portamento and hears arpeggiated minor chords and common motifs including one she abbreviates as SLD2: “a short-long articulation on two pitches that are a descending second (major and minor) apart.” She notes particularly that the avian use of mimicry has a parallel in the human tendency to copy or appropriate others’ music and cites the longstanding tradition in Western music of writing variations on borrowed themes. Taylor notes recent neurobiological evidence that songbirds’ imitative powers are linked to what is perceived and are thus not purely mechanical or functional. Finally, she challenges the assumption that cultural activity is restricted to humans, suggesting that “the capacity for vocal learning and copying that we share with songbirds but with no other primates is deeply entwined with our essence, the essence of our music, and the essence of a bird’s song.”

Taylor systematically refutes the various objections to the proposition that birdsong can be music, for example that only humans can make music or create culture, or that birds can’t learn new material or that birdsong does not conform to western musical tuning. Butcherbirds rehearse, they learn new songs and sounds, they create variations on their own themes and they perform where there is no apparent bird audience, that is they appear to perform for themselves. Duetting birds learn to synchronise their song and there can be interspecies cooperation. Intervals in phrases, where unnecessary for breathing and therefore voluntary, create musical form. She cites many other bird species with highly developed song and refutes the idea that birdsong exists only to mark territory or attract mates. “The time has come to abandon our uncritical preference for human achievement—specifically for my purposes, to decentre the human in music—and instead to be open to the possibility of creativity and agency in animals.”

Is Birdsong Music? is an absorbing and delightfully written field diary as much as it is a technical analysis of sound and a philosophical discussion of the concept of music, and it extends her 2008 article “Decoding the song of the pied butcherbird: an initial survey.” Taylor has undertaken many years of dedicated work in the outback trying to find and record butcherbirds, often before dawn in pitch darkness. Venomous snakes, frogs in the campground toilet, dogs and dingoes, the heat, flies, mosquitoes and disruptive locals—the obstacles and dangers facing the ornithologist are manifold. Her research methodology involves the sonic and musicological analysis of field recordings and the documentation of the date, time and location of birds’ singing. She eschews laboratory research and other active intervention, wishing to leave the birds undisturbed. What comes through clearly is Taylor’s utmost respect for the environment generally and for birdsong and butcherbirds particularly.

Why should we dwell on the question of whether the definition of music should be broadened to encompass the music of other species? Firstly, we give inadequate attention to sources of superb sounds which we believe are worth less than our own. Secondly and more importantly, Hollis Taylor’s book encourages us to recognise the importance and interconnectedness of all species. She challenges the dominant view that humans represent the pinnacle of all life and can act independently of the environment. The cultural connection between species is integral to environmental connection. An essential principle behind the recognition of birdsong is the very recognition of birds and her final chapter addresses the biodiversity crisis, highlighting Australia’s appalling record of environmental degradation. The butcherbird ensemble at Esk has now disappeared and butcherbirds are silent in other regions where she has previously recorded them, though she concedes that their absence from these regions could possibly be temporary. We must be alert to the needs and the beauty of birds in all locations.

Visit the Pied Butcherbird website.

Enjoy excerpts from the Absolute Bird double CD set, which is also offered as a RealTime Giveaway this week, below.

“Owen Springs Reserve, 2014” by Hollis Taylor and Jon Rose for vibraphone (Claire Edwardes) and field recording.

“Green Lake, Victoria” by Hollis Taylor for soprano recorder (Genevieve Lacey) and field recording.

–

Hollis Taylor, Is Birdsong Music? Outback Encounters with an Australian Songbird, Bloomington: Indiana University Press; Music, Nature, Place series, 2017; Hollis Taylor, Absolute Bird, double CD set, ReR Megacorp, 2017

Top image credit: Hollis Taylor, photo Jon Rose