Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Sandy Edwards, Marina and Laura in Lady Grounds Pool,

Sandy Edwards, Marina and Laura in Lady Grounds Pool,

Bithry’s Inlet, Tanja, NSW, 1998

Indelible represents the suite of images that remained after photographer Sandy Edwards spent months viewing, re-viewing and culling the hundreds of rolls of colour film of family and friends that she had shot over the last decade. The images record Edwards’ visits to some of her favourite haunts, such as New York City and the New South Wales south coast, as well as documenting certain rites of passage and leisure activities of her close personal network. A child opens a Christmas present while another squirts a hose at the camera; a pair of adolescents pose in formal wear while others lie face down on the surface of a rock pool; a girl surveys a wedding reception, while another warms her legs by a fire.

The challenge faced by the artist, as Edwards herself describes it in her room-sheet notes, was the transformation of these images from personal snapshots into an exhibition with broader, or ‘universal’ appeal. Edwards has attempted to achieve this through honing in on content, selecting representations of those moments in life to which most of us are witness, events that mark the passage of time or personal change, such as weddings and birthdays, holidays and house-warmings.

There are several perils in such an approach. One is the by now familiar dubiousness of the traditional documentary photographer’s credo of truth and objectivity. Another is the equally problematic nature of any appeal to the ‘universal’, whereby culturally specific assumptions are necessarily made but not always acknowledged. Further, there is the related risk that in aiming for the general, one might lose the poignancy of the particular.

Edwards may have run these risks, but her erudition and experience allow her to navigate them, albeit with varying degrees of success. Her role in the documentation process—the images are to some degree autobiographical, with the artist herself appearing on occasion—is explicitly acknowledged, underlining the subjective nature of photography. The titles of the photographs locate them very specifically in time and place, as does the frequent reliance on the genre of portraiture that heightens the individual identity of the subjects; clearly these images are less universal than representative of a particular class and lifestyle. However, despite this, some of Edwards’ images fail to engage, and appear to suffer from a lack of intimacy. Perhaps, in seeking a more public mode of address, Edwards has at times sacrificed a personally charged register.

There is a sense of emotional reticence about some of the images, as if any scenes deemed too intimate or revealing have been edited out. For example, awkward moments are not really tackled, although there is a moving hint of discord in one title that tells us the artist’s mother no longer wishes to be her daughter’s subject. Indeed, at times the portrayals tip into the anodyne, remaining unremarkable and prosaic, not unlike those shots in an ordinary family album that attempt to evoke the significance of events through their sheer quantity rather than through a definitive image.

As a result, it is those photographs tending to the abstract, which demand a shift in the mode of spectatorship, that are the strongest and most evocative. When Edwards’ unmistakable eye for colour and composition is most in evidence, her photographs come alive for this viewer, as in the vibrant contrasts in Merilee’s hands, where fingers are outstretched to a pot belly stove and clothes highlight pattern and colour; or the cool sinuousness of Lisa’s legs in mum and dad’s pool; or the delight in the abstract arrangements haphazardly created by Adrian’s sarong blowing on my mother’s clothesline and Byron Bay Classics cozzies. The appeal of such images lies largely in Edwards’ ability, through her formal strategies, to transform the unremarkable into the aesthetically delightful. Her photographs infuse the ordinary with beauty in such a way that the viewer can bring a refreshed vision to his/her own surroundings, with eyes more attuned to colour, pattern, correspondence.

One correspondence that repeatedly structures Edwards’ images is between people and nature. A certain unapologetic Romanticism permeates her compositions: people are often shot in natural landscapes, or at least in contact with natural elements such as fire and water, with an emphasis on ‘naturalness’, ‘immediacy’ and ‘sensation.’ The urban shots, by contrast, tend to be less inhabited: fragments of the built environment, such as a neon sign or pedestrian crossing, stand as synecdoches for the city, while portraits shot in the street are closely cropped to limit the allusion to place.

While the emotional reticence and prosaic nature of some of the images detract from their power, this is counterbalanced by the formal rigour, aesthetic empathy and affirmation of human/nature interaction in others. On viewing this exhibition, I was reminded of Susan Sontag’s observations in her recent book about the ethically dubious nature of “regarding the pain of others.” Perhaps in offering us images of everyday beauty, Edwards is honing our powers of attention more effectively.

Sandy Edwards, Indelible, Stills Gallery, Sydney, March 17-April 17

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 45

© Jacqueline Millner; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

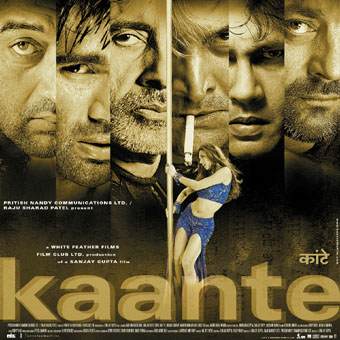

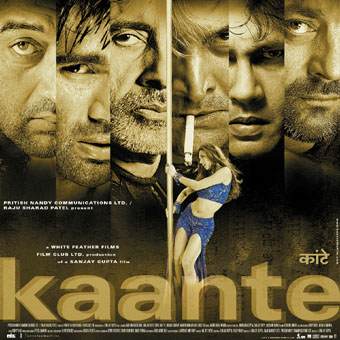

David McDowell, The Passenger

Courtesy Canberra Contemporary Art Space

David McDowell, The Passenger

In The Passenger David McDowell explores the contrast between still images and time-based video as a way of demonstrating the traveller’s experience of time. These 2 media forms remain separate in this large installation, in which the artist sets up a tension, yet narrative connection, between motion and stillness.

Large panels hang around the gallery like makeshift walls in a theatre set. Each panel comprises a grid of separate stills. Printed on transparent film stock, the back-lit images resemble projected moving images, only they are motionless moments caught in time. The fragmented surface is deceptive, with each still like a David Hockney photograph, capturing part of a larger image. With different depths of field for each fragment, it takes some time to focus and decide whether the panels in their entirety capture the vista of a passing mountain range, the view through a travelling car windscreen, an aeroplane wing on a tarmac, or sleeping passengers in a transit lounge. It is as if you have lost your focus in that moment of travel through unfamiliar places.

The artist seems to revel in the romance of older forms of apparatus used to capture and display images, alongside an acknowledgement of modern technologies like the domestic handycam. The lighting set-up on the panels recalls the bygone era of slide projection and the family display of slides from overseas trips. The stills, printed in muted tones, have a warm old-fashioned feel, with the light seeping through from behind. Each image looks like an old monochromatic photographic plate that you hold up to the light to see detail. They reminded me of a very old clunky projector that my father had, which required the viewer to slide in each precious glass plate to bring the image to life on the wall. The notion of projection in these static images intersects with the 2 centrally placed video works when you enter the gallery.

The first video work you encounter is screened on a monitor. The second is projected onto a hanging panel constructed from the same materials as the panels of photographs. The video on the monitor has a highly compressed quality, making the image blurry and again hard to focus on. The projection seeps through the hanging panel and can be seen in fragmented parts on the back. Both videos capture a moment of travel; a plane leaves the tarmac on the monitor and a car drives through a tunnel in the projection. These moments of time are slowed down and looped in an endless monotony. There is a connection with the still imagery combined with a sense of dislocation, of the world passing by while you are standing still and going nowhere. I got caught up in the tunnel and found a connection with the low droning audio track that permeated the space of the gallery. The soundscape seems to use treated environmental recordings, which can only occasionally be synched with the moving images. There is an instant where the sound of truck brake exhaust can be linked with truck headlights gliding through the frame. Placing these sounds with the moving images resonates with our attempts to focus on the wider image on the panels and form some kind of connection and escape from the shifting terrain of being a moving passenger.

In The Passenger, David McDowell uses the differences between stasis and movement to play with our perception of time, questioning the progressive narrative of the moving image. The viewer reading the panels pieces together static fragments to create a scene. The viewer watching the moving imagery arrives in the looped narrative and travels only part of the journey, never really going anywhere.

The Passenger, photo and video works David McDowell, sound Somaya Langley; Canberra Contemporary Art Space, March 26-May 1

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 45

© Seth Keen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

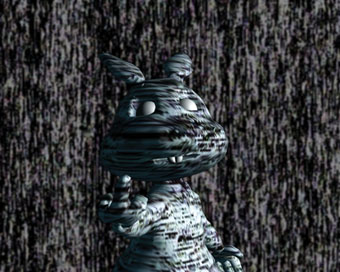

Ricky Swallow, Killing Time (detail), 2003-2004

Courtesy of Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney

Ricky Swallow, Killing Time (detail), 2003-2004

In the middle of a darkened space sits a heavy, old fashioned and roughly hewn kitchen table. A single spotlight illuminates fruits of the sea spilling out over the table top: dozens of oysters, a crayfish on a plate, squid, snapper, mullet and garfish. A knife rests on the edge, next to a lemon that is partly peeled, its skin curling away off the table. This cornucopia is laid out for our viewing pleasure.

Ricky Swallow’s sculpture/installation Killing Time possesses a ‘gasp’ factor that turns adult viewers into kids dying to touch. What takes our breath away is the fact that nothing is as it appears. The entire work—from the fragile curling lemon peel and the finely wrought legs of the crayfish, to the bucket and folded cloth—has been meticulously carved out of wood. Swallow’s mimetic skills are awesome and his ability to re-present reality captivates audiences who can’t seem to help taking a ‘reality check’ through physical contact with the work. Little wonder the gallery positioned an attendant to watch over it.

Ashley Crawford wrote in The Age (April 17) that Killing Time is based on Swallow’s childhood experiences as a San Remo fisherman’s son. Without doubt this work is personal, but it connects with viewers on a far more profound level. For all the carving skill demonstrated in the recreation of this laden table the work is disconcerting. There is no tell-tale fishy smell or seductive colour, no sounds of laughter or kitchen noises that such bounty would engender. It is as if all the life and colour has been bleached out of the scene.

Given that Swallow dedicated 6 months to crafting the work, Killing Time is an apt title. However, the title, the dramatic chiaroscuro lighting and the tableaux link the work to the Dutch and Flemish traditions of still-life painting or natures mortes— literally ‘dead life’. Seen in this light, Killing Time potentially takes on a political edge.

At a literal level, Dutch still-life paintings offer a skilful mimetic rendering of simple everyday things. However, simultaneously these everyday things assume symbolic meaning, a warning against the seductiveness and emptiness of material excess, reminders of the need to maintain balance between the spiritual and carnal. Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s La Raie (The Rayfish, 1728) for example, warns of the danger of licentious living, through its juxtaposition of sexually laden symbols: a cat with its hackles risen, oysters, jugs, the underside of a rayfish and a knife balanced on the edge of the table with its blade thrusting into the delicate folds of the tablecloth.

The similarities between the composition of Chardin’s La Raie and Swallow’s Killing Time begs a reading of one through the other. In La Raie, we are also presented with a rough hewn kitchen table groaning with seafood. And I ask: What does it mean to show the underbelly of a rayfish or to present a profusion of oysters? Is the knife balanced on the edge of a table just a knife or does it signify how delicate the balance of life is? Why is Swallow’s knife balanced on the edge of the table? Is the half peeled lemon hanging precariously off the side of the table intended to show the virtuosity of the artist, or something more significant? And why has the artist presented the crayfish with its underbelly to us in a state of helpless vulnerability and impotence?

In the silence of the gallery space viewers have responded to Swallow’s work in whispers and with an almost religious reverence. Yes, the work is a virtuosic feat. However, in the tension between its tactility and untouchable fragility it demands that we do more than just gasp in awe. In his interview with Ashley Crawford, Swallow makes the evocative comment that Killing Time is something to do with “owning up.” Perhaps this is what the work is asking of us.

Ricky Swallow, Killing Time, Gertrude Contemporary Art Space, Melbourne, April 2-May 1

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 46

© Barbara Bolt; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

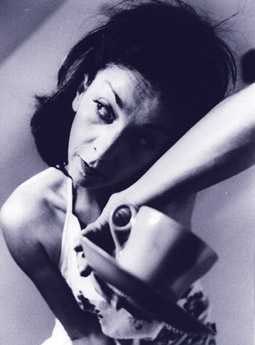

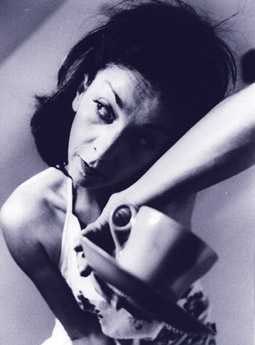

Maria Blaisse, Silverspheres, 1989

photo Anna Beeke

Maria Blaisse, Silverspheres, 1989

Remember when we dreamt of cyborgs and talked about “becoming” as if it all actually meant something? As if it was possible, this future of endless human plasticity? It seems naïve now that we’ve grown beyond the narcissistic phase of our social evolution and have a better grasp of the limits of our bodies. Now that we remember before bodies mutate they break, mash, incinerate, humiliate, decapitate. Humpty can’t be put back together again.

It’s because of this that I feel if I was looking at the work of Marie Blaisse at PICA, say, 5 years ago, I might have had a different reaction. Today I cannot help but respond with a sort of melancholy; that of the disenchanted futurist. Blaisse’s work was for me a phantom limb, missing but present, a reminder of a whole we once enjoyed, that we maybe took for granted, made too much of. As such, it is somehow more than just Lucy Orta for jazz ballet fans…as the faintly thrumming pain throughout this latently morose show gives it a kind of dignity I wouldn’t have thought possible.

Admittedly, these sombre reflections were far from my mind when I first dipped into the show. It did what I’d thought it would: reactivated all the striving playfulness of the 1980s and early to mid-1990s. The retro, brightly coloured foam costume pieces Blaisse is known for were strewn about the floor with a casual, licorice allsort quirkiness. A few dangled from the roof. The feel was Yazz meets Bananarama downtown at Mangoes for Shirley Temples—light, giddy, soft. This cutie harmlessness was amplified by the kids playing with the costumes, supervised by smiling, good-natured gallery staff. They placed tubes on their heads, slotted skinny arms through cymbal-like shapes. It was goofy good times and arty/fashiony merriment.

This feel was matched in the Paula Abdul video piece where dancing fascists in Blaisse-molded attire gleefully gyrate and hump and goosestep and jitterbug and arse-bounce. Foam-fattened cartoon frames for the Abdul stage show, they were more properly part of an extended extravaganza that had begun with Kiss or Bowie and led to Michael Jackson and worse and then worse still. Art or fashion (or whatever the hell Blaisse does) was a stadium act, just for a moment, but in the process was reduced to being simply part of the era’s dominant culture’s yearning for surface glitz. It’s worth comparing Blaisse’s work for Abdul with Cirque de Soleil’s efforts for New Order in the True Faith video. The French company used a similar aesthetic but to a more rabidly creative and compellingly artful end. Blaisse’s effort couldn’t escape the gravitational pull of the middle-of-the-road. It ended up as its road kill.

Naturally, this satisfied-with-itself escapade was the least interesting part of the show. The film work (produced in collaboration with dancers/models and filmmakers) was an altogether different experience, albeit one that revealed its intensity only on repeat visits. It took solid time and effort to clear away the surface froth to get at the fragile, haunted skeleton of this richly cold work. In one monitor-based work, for instance, we see a woman wrestling with gravity wearing a red, bud-shaped hoop around her waist. One moment she’s Kafka’s giant beetle who cannot right itself. Next she’s Minnie Mouse. Then a ladybug. Oh, metamorphosis is just so fucking hard.

The other works, tucked away in the screening room, took this dynamic to another level entirely. Immensely, awkwardly artful and fun—Godard for the Xanadu generation—they were full of unexplained, unexplainable jump-cuts, formal interruptions and visual and auditory non-sequiturs. Uniting this strange fruit was the fact that the otherwise graceful models who sport Blaisse’s works are forever struggling with the limitations of their new appendages. Blaisse’s bodily additives are definitely, defiantly prototypes. The films are test runs. The models are the fashion world’s equivalent to crash test dummies (which maybe they always are?). My favourites involved rollerskating women (precursors to the genius video for Cat Power’s Cross Bones Style?). One skate flick features a gal with elongated arms connected to her feet. She’s a bug bent on all fours, but not quite; suddenly the arms dislodge from the feet, and she doesn’t know what to do. Then she (or was it a man?) is spinning around, legs splayed thanks to a foam insert.

The rollerskates are significant here. Both skates and the foam body attachments extend and amplify bodily pleasures. Despite this, the logic of the films offers pleasure and then achingly hems it in: the performers are specimens acting out their limitations and possibilities in rooms of clinical clarity and texturelessness. Ultimately, this instills a sense of elegiac melancholy that overrides any overt playfulness and evokes more than a whiff of S&M (in the Freudian sense).

So when, as in the glorious images of a woman’s back turning into a dove, the body reaches a state of grace, it does so surprisingly, as a temporary release made all the more sweet because of its cloistered context. What is clear is that elegance is also a result of being frozen rigid. Indeed, in the still shots of Blaisse’s work on models, the body is pure graphic. The head appears severed from the body. Limbs protrude, a new being is created. The film works, though, show that this is merely an empty promise. The condition of human as graphic is an interlude, a fantasy, a projection of art.

Of course, Blaisse’s work activates these dynamics within a very precise context of sartorial modernism. Elements of futurism and surrealism fuse with 1960s design sensibilities of a Panton-gone-to-the-Moon flavour. There’s something retro-futuristic about Maria Blaisse’s work, but it has learnt from, and moved past, its inherited utopianism. Nevertheless, the thin margin for pleasure, within and against restraints, is obvious and locates her alongside designers such as Belgian Martin Margiela who continue to make fashion along the line between containment and chaos.

Curiously, the flaws in the show’s presentation, while initially annoying—the lack of labels, monitors running side-by-side with inaudible sound—aided the Blaisse effect. Blaisse’s work is best approached at a remove, as a memory trace, as a gesture that doesn’t hold. At its best it opens up the problem of being human, at its worst it is a distraction. It’s pleasure and pain, pop and philosophy, lycra and foam as existential fundament.

Marie Blaisse, Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, April 1-May 9; part of The Space Between: Textiles_Art_Design_Fashion

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 46-

© Robert Cook; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

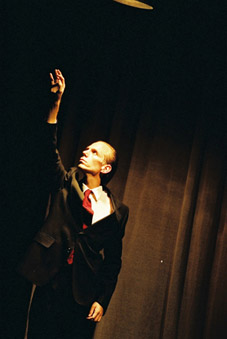

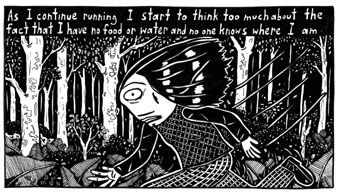

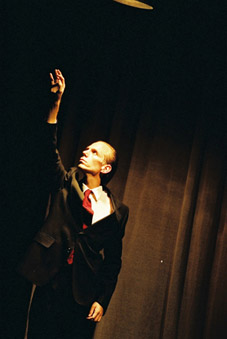

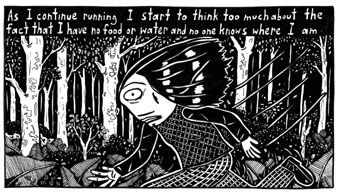

Martin Del Amo, Unsealed

photo Heidrun Löhr

Martin Del Amo, Unsealed

The performer smiles. She’s met a policewoman who has confided tales of her dysfunctional relationships. She makes a series of tentative moves, a little half dance of self-protection, a hand swinging almost instinctively over the groin. She moves along the wall, a dance suggesting impact and defence. An alarm summons her to a desk where she operates a transcription machine with her foot while typing the policewoman’s words onto a laptop (for us they unfold on the screen behind her). She stops, rewinds, catches up, ignores errors, speeding on as the story spills out. In it the policewoman transforms from victim to defender to near-murderer of her attacker, her partner.

The performer joins us at the front of the space, sitting, smiling, commencing a slow, silent writhing and twisting, conveying a desire to burst free, but also strain, the anxiety of the almost-murderer as the recorded voice runs backwards in aural space around us. Eleanor Brickhill’s performance in An Unknown Woman is the embodied emotional aftermath of the story, it is an act of empathy, acknowledging moral complexity, a taking in of a story and of a fellow being. This short, tautly contained work makes an intriguing companion piece to Kay Armstrong’s The Narrow House in which we see the premeditation of a female murderer (see article).

In Stand Still, a small precise work, 2 dancers share a space, together and apart, but never in a duet. One turns and turns, slowly, an arm out, leading. The other’s simple articulations suggest semaphoring, a vertical to the first’s horizontal reaching and turning back in. Stillness. They start up again, the movement slightly faster, more articulation, greater extension, Nalina Wait is fluid, bending at one knee to reach out further, arms arching out, hands in to meet with a sense of completion. Lizzie Thomson opens out and up, more angular, less certain. Stillness. Here too is empathy, across different forms and rhythms, sharing the same space, the same momentum and stillnesses, like a dialectic that almost but never resolves.

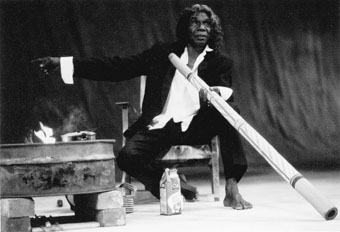

A man paces in his underwear. Is he lost? Looking for something? Mapping out space? The walking becomes almost hypnotic, its obsessive footfall subtly extended by a sound score evoking stranger spaces than the one we see before us. Between these walkings (rectangular mappings, sudden diagonals, impulsive stop-starts, on the spot reachings-up like involuntary signallings, half-squats, circlings) the man stops, faces a mirror, wipes himself down, drinks water. These are quiet, slow moments. He looks at himself. Each time he stops here he adds an item of clothing before coming to address us, or, once, singing…before setting out on another, more intense walk, the sound score sometimes pulsing as if rippling through him and, in a rare moment of extroversion, suggesting a demented carnival.

He addresses us quietly. He’s been to a psychiatrist, not that he’s off the rails, “but if the rails are not clear…” It’s about loneliness he says and the thin line between self deception and self perception. About what you want to be…a singer? Is it about happiness? He thinks we can get “homesick for sadness…we wouldn’t be happy without it.” Later he talks about a moment in his flat, an impulse to destroy, and acting on it, tearing apart magazines, documents, passports…but, unable to let go, keeping them in blue plastic bags sitting on the top of bookshelves. By the time he sings, a searching, fine interpretation of a Friedrich Hollaender and Robert Liebmann cabaret song, he is fully dressed. The suit appears to contain him, bulking the strange reaching gestures—a half-hearted aspiration for transcendence? He walks again, looking to connect. He stops, he shudders.

The piece resonates with the nuanced musings of Gail Priest’s improvised sound score which involves the miking of the space to pick up, amplify and ever so slightly alter del Amo’s footsteps, breath and movement. When he sings, the increasing resonance has the effect of separating the performer more and more from the real world as he retreats into that of the cabaret singer, and also pushing the microphones to the point where they too ‘sing.’

At 40 minutes, Unsealed is a complete, quietly disturbing, confiding and important work from Martin del Amo that makes an art of walking, invites our empathy and offers a sad paean to the virtues of melancholy.

Performance Space, Parallax: An Unknown Woman, Eleanor Brickhill, sound Michelle Outram; Stand Still, Nalina Wait, Lizzie Thomson; Unsealed, Martin del Amo, sound Gail Priest; design Virginia Boyle; producer Fiona Winning, lighting Simon Wise, project coordinator Michaela Coventry; Performance Space, April 21-May 2

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 47

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

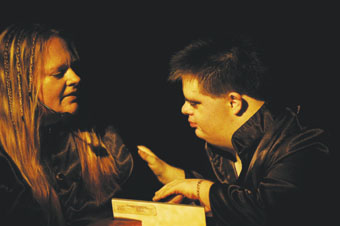

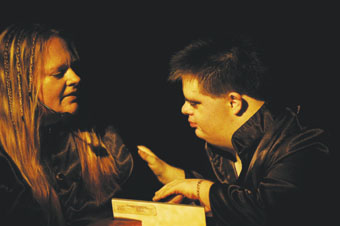

Kay Armstrong, Narrow House

photo Heidrun Löhr

Kay Armstrong, Narrow House

Experiencing Kay Armstrong’s The Narrow House is like getting into the head of a murderer by way of her body, her words and into the evolution of a psychosis, onto the planning and into the crime. It’s a claustrophobic trip as the will to act forms and the rehearsal of the murder forces choices. Naked seduction followed by a knifing? Or a cup of poisoned tea served with domestic grace in an apron? The fantasy is full-bodied, sexual, likely bloody; the fact is the female murderer’s favourite, the inversion of nurturing: poisoning.

Unlike John Romeril’s early work Mrs Thally F, a play about a real Australian poisoner, Kay Armstrong’s murderer is an invention but a nonetheless convincing one. This worryingly sensual, perversely poetic dance theatre work is about a consuming state of being. As the passion escalates we see the murderer across the theatre’s pitch dark spaces through various psychologically refractive perspectives. She’s a naked woman (self-)fondled in a kitchen window. She’s a close-up confidante of the audience. She serves tea at a table over which a mirror swings low so we watch her from above, doggedly rehearsing the increasingly mad moves of her murder. She appears in a distant corner of the ceiling like a spider alert in her web. She’s disembodied, projected onto a wall perpetually entering the crime scene-to-be.

But it’s in the naked and vulnerable but aggressive body that we see both the desire and the torment of the compulsion, an idiosyncratic and increasingly tormented dance to an unseen force that tugs at her, drags the woman off-centre. It’s a barely controlled agony heard too in Garry Bradbury’s rich, enveloping sound score. This body connects only with a few objects in this closed universe: a large, threatening kitchen knife, a bone china teacup that glows like the Grail and a statuette of the Virgin. The Narrow House is an absorbing and disturbing creation. Armstrong’s writing needs distilling and her acting more restraint, but after some tentative and difficult steps towards creating her own brand of dance theatre, she has now proven herself capable of a bracing totality of vision, not least in the self-choreographyof an aching dance of limbs, of a body dissociated as painfully as its psyche.

One Extra, The Narrow House, performed and choreographed by Kay Armstrong, dramaturg Nikki Heywood, composer Garry Bradbury, video Samuel James, lighting Simon Wise; Performance Space, March 10-21

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 48

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

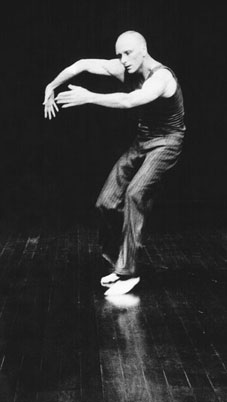

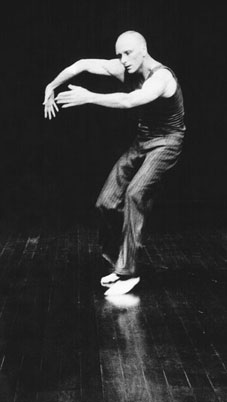

Sue Healey, Fine Line Terrain, 2003

photo Alejandro Rolandi and Kate Callas

Sue Healey, Fine Line Terrain, 2003

Choreographer Sue Healey is a survivor in the Australian dance scene. Beginning her career with Dance Works (1983-88), Healey led the Canberra-based company Vis-à-Vis from 1993-95. Since then she has choreographed independently, creating works for a fluid company of dancers which has included Michelle Heaven, Philip Adams, Jennifer Newman-Preston, Shona Erskine and Nalina Wait. She has been commissioned by many Australian dance companies and has an ongoing relationship with the Aichi Arts Centre in Japan. Healey has worked with filmmaker Louise Curham (RT58, p15) on several film and installation projects since 1997 and has recently begun directing her own films, including the award-winning Niche (2002) and Fine Line (2003).

Healey is currently a Research Associate with the Unspoken Knowledges Research project, led by Professor Shirley McKechnie at the Victorian College of the Arts. Her recent Niche series has been part of McKechnie’s project and consists of 5 works created between 2002 and 2004: the films mentioned above, 2 live works (Niche/Japan and Fine Line Terrain) and an installation (Niche/Salon). Healey’s finely crafted, intricate choreographies are too rarely presented in Sydney and her upcoming season of Fine Line Terrain at The Studio (Sydney Opera House) has been much anticipated since a showing of the work last year. Since then, the piece has been performed in Auckland, Canberra, Melbourne and New York.

Healey talked to RealTime about the logic behind the Niche series, her interest in space and perception and the challenges she faces as an independent choreographer working with an increasingly consistent company of dancers.

The Niche series covers 5 works and has traversed a number of formats: film, video, installation and performance. Why a series and how is the variety of formats tied to your exploration?

Each work ‘found’ its own niche, so to speak. I started with a dance video focus—wanting to make dance for that specific space rather than my usual method of choreographing the action before its translation into video or film. As our focus was space, it made absolute sense to keep finding new spaces and contexts to explore, manipulate and extend our material, including the screen space, a traditional proscenium space, a white gallery, a new cultural context (Japan) and a ‘site specific’ (30 metre deep) space. I didn’t set out to create a series—it evolved quite organically. I can look back and see that the driving force was a search to place the ‘right’ work in the ‘right’ space.

You are particularly interested in movement and perception. How does this relate to your use of both live and screen formats?

I am not interested in dance as fashion or in movement that disengages perception. I believe that art can make a difference to the way we live our lives. (Experiencing) dance, whether as observer or performer, can enhance the way we perceive our reality as moving, sentient beings interacting on this fragile planet. Perhaps it is even vital. I explore this in both live and screen formats. My current choreographic research is devoted to the manipulation of time and space that video and film makes possible and which offers me a range of new devices only dreamt of when creating live performance. However, I think I will always need to have the visceral, the physical, the real, underpinning the work I create—to keep in touch with the tangible physical drama that occurs as you choreograph. This is because I highly value the memories of performing that I have in my own body.

You have a very strong group of dancers working with you now. How important is it for you to work in this way and what is the real economic viability of such relationships?

The dancers I work with are simply extraordinary. To say that they are fundamental to my process is an understatement. It is a top priority for me to maintain the relationships I have with my dancers. Sustaining employment opportunities for these dancers is the toughest aspect. I can only employ them for short periods scattered throughout the year—I can’t offer them any financial security. What I can offer is a creative framework that has an ongoing sense of development and support. This has been a successful model for us over the last couple of years. For example, Shona Erskine worked on every stage of the Niche series through an initial mentorship grant from the Australia Council. This sense of an ongoing partnership is unusual and difficult to achieve outside of a company scenario.

The difficulty lies in timing grant applications and negotiating around dancers’ other contracts, juggling dates, venues, budgets, schedules, in the hope that providence will bring everything together. Strangely enough it mostly seems to work out. At times I do wonder, however, about the work I could be making if things were different. I do have an occasional lusting for a company model that provides ongoing administrative and production support. Having had that previously, I do think that I have found a unique structure to create within. The success of the Niche series bears witness to this so I think I am on the right path.

–

Fine Line Terrain, choreographer Sue Healey; dancers Victor Bramich, Shona Erskine, Lisa Griffiths, Nelson Reguera Perez, Nalina Wait; lighting Joseph Mercurio, composer Darrin Verhagen; The Studio, Sydney Opera House, June 29-July 3

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 48

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tasdance, Light and Dark

photo Paul Scambler

Tasdance, Light and Dark

Light and Shade explores the boundaries, spaces and possibilities of darkness and light, blurring the notion that light is pure while darkness is a menacing force devoid of innocence. Conceived and curated by TasDance’s artistic director Annie Grieg, the show comprises Swimming the Luna Sea by Chrissie Parrott and Tanya Liedtke’s Enter Twilight.

In the opening sequence of Luna Sea, entitled “Dark”, Parrott situates 3 male and 3 female dancers in a stark and shattered landscape. Jonathon Mustard’s sound score of rainfall, howling dogs and the relentless creak of timber enhances the sense of unease and loss. Accomplices and competitors in an alien place, the dancers move between corporeal claim and counter claim of initial touch and support, to the squared-off angular movements of threat and abandonment.

In this space of lunar dispossession the ensemble (re)enact the frisson and fragility which co-exist in the habitual province of human encounter, potential and rejection. Theresa O’Connor’s lighting design has a precursor in the hoary light we associate with the first moon landing. The semi-dark state enhances both the group’s isolation and their body motifs: the recurring minutiae of a dancer’s clawed hand, a finger flick, an inverted foot, a jagged hip.

A stone rolls from one cheek to another, momentarily counter-pointing the alienation of place and space. Words have yet to assume the shape and potency of meaning. Consonant and vowel provide an aural ostinato, as sound stumbles on the tongue and splits around the mind’s incomprehension. Each dancer’s physical vocabulary moves between recall of lost humanness juxtaposed against the whip-strength and aggression of a non-human state. They move from acquiescence to a dominance of each other while remaining submissive to the hiss and whisper of a landscape before language.

The apprehensive mood shifts in “Light”, the second section of Luna Sea. Trisha Dunn appears as a White Dew figure draped in a silver gown and shedding astral dust. This figure of innocence and immanence offers declamatory gestures. She mouths half-realised sounds suggestive of a seer uttering fragments of language, which allay the sense of estrangement and terror.

Three bare-chested male dancers glide in white-hooped skirts like retainers in an imagined Tutankhamen court. They present an image of beauty and quirkiness as the dancers’ weighted skirts swing and wrap their bodies. When pulled over the head, the skirt accentuates the dancer’s facial structure through a taut cloth mask. Moving like wraiths in space, Craig Bary, Ryan Lowe and Malcolm McMillan offer gestural homage to White Dew as they mirror her hand motifs. This provides an enlivened and illumined resolution after uncertainty and darkness.

Tanja Liedtke is a choreographer who re-imagines the parameters and possibilities of dance. Her choreographic finesse in Enter Twilight explores the paradox that exists within life’s rituals through the allure, seduction, playfulness and danger enacted between a male and 3 female dancers.

Craig Bary sleeps on stage while 3 young women—Trisha Dunn, Lisa Griffiths and Tania Tabacchi—observe, chat and speculate. Liedtke knows how to set her dancers on a trajectory that makes deft and detailed use of the body. The performers split and navigate space, generating a simultaneous allure and frisson of excitement. They reveal the paradox of dangerous states teetering between humour, innocence and treacherousness.

This dance is stylish, pert, cheeky and flirtatious. Each girl targets, then engages in an alternately naïve, groovy and sensuous dance conversation with the boy/man. The dancers whisper and tease, embarking across the terrain of taunt and threat implicit in relationships. Composer DJ Tr!p’s lo-fi electronic sound score projects the crack, scratch and pop of tired vinyl, the result of too frequent playing by kids making their moves on each other and the world. Seated dancers are intriguingly lit from beneath as they glide around a wooden bench in playfulness, entanglement and pursuit.

Liedtke’s strengths include inventiveness and visual surprise. In one sequence each dancer falls and rebounds from the floor as an agile unit of momentum. The reversed upward movement is like watching a film in slow motion replay. In another visually arresting moment, 3 pairs of inverted legs disconcertingly appear in space, luring the eye away from the site of action.

Swimming the Luna Sea and Enter Twilight use the languages of the body and the tongue to illuminate the territories of light and shade, seduction, corruption and desire.

TasDance, Swimming the Luna Sea, choreographer Chrissie Parrott, music Jonathon Mustard, lighting Theresa O’Connor, design Chrissie Parrott with Darren Willmott; Enter Twilight, choreographer Tanja Liedtke; music DJ Tr!p, design Tanja Liedtke with Darren Willmott; Hobart College Auditorium, May 6-9

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 49

© Sue Moss; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

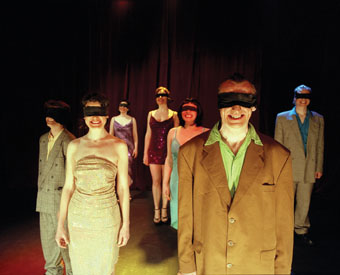

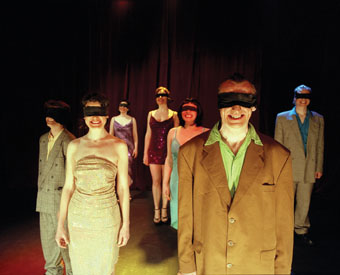

Lily Noonan and Sylvia Claridge, Age of Consent

photo Tim Hughes

Lily Noonan and Sylvia Claridge, Age of Consent

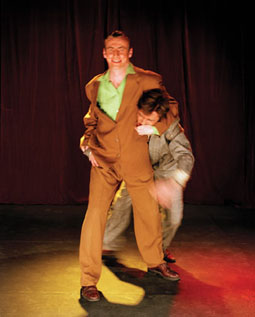

A radiant turquoise wall seeps pink light, warmly greeting audiences arriving for Stompin Youth’s latest dance work, Age of Consent. A futuristic vending machine requires us to speak into it before tickets are dispensed with a too soothing voice oozing automated menace. Extra-terrestrial lights crane above the hall’s tiered seating, to which we’re escorted and allocated age-tags. The space fills with urgent, automated whispers, sweeping us through a reverberating void.

The entrance wall of milk-crates is reconfigured to form 5 dividing walls on a central platform, each containing a peephole. The walls allow half the audience to partially view scenes played out before them, while the remaining half are privy to the uncensored version.

The vignettes—a girl dancing seductively in her room, young people venturing first touches, the surreptitious application of makeup, shotgunning a can—depict the forbidden in a voyeuristic form, while sound effects and voiceovers snake around the walls. In this way the work rotates and gradually unfolds on a spare yet cleverly devised set, reminiscent of Lars Von Trier’s Dogville and similarly functioning to bring the drama into sharper focus.

The set is suddenly and violently dis-assembled to the tense rhythm of a bouncing ball. Mattresses are introduced and the sexes divided. In a nice inversion, boys preen and groove in a nightclub while girls lounge and leer. As the night progresses, intoxication is conveyed in limp, puppet-like movement, accompanied by a slow, aggressive soundscape. Trouble could be just around the corner and there’s a sense of clinging eroticism, at once languid and intensely menacing. Voiceovers recounting bouncer/ID stories drop the intensity, but the energy rises again with a montage in which a progression of dancers is each asked to ‘act your age’ to dramatically different pieces of music.

Composer Luke Smiles manipulates electronic recordings live, dropping or accentuating layers in response to the energy of the performance. The symbiosis achieved between sound and choreography is one of the strongest aspects of Age of Consent and the director, Luke George, believes this is largely attributable to Smile’s considerable experience as a dancer.

Age of Consent emerged from an exploration of the written and unwritten codes that pervade and influence young people’s lives. A 12 month creative development involved 30 young dancers. Luke George says he was careful not to impose his stylistic preferences, preferring to shape the dancers’ own responses to the subject matter. The exception was the final sequence in which 2 groups of dancers move in formation to the rattling pulse of marching drums, but with an ironic twist. Influenced, he says, by the “highly objectionable Bitch Rock” band Peach, George introduced a defiant shoulder thrust, to represent the way it feels to ‘break the rules.’ Military elements gradually dissolve into ecstatic anarchy and Stompin’s trademark electric energy—a fitting finale.

Stompin Youth Dance Company, Age of Consent, director Luke George, sound Luke Smiles, design bluebottle; Pilgrim Hall, Launceston, May 6-9

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 49

© Susanne Kennedy; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Simon Pummell, Bodysong

Micronations

On September 2, 1967 Ex-Major Paddy Roy Bates decided to occupy an ex-World War II military sea fort just off the East Coast of England and have it declared a separate nation state. The principality of Sealand was born. Thirty seven years later Prince Roy, as he proclaimed himself, has handed over the throne to his son Michael and managed to gain de facto recognition of its sovereignty from a number of European countries. Over 25 years, lobbying the UN for nation state status has so far proved unsuccessful.

Sounds fanciful but it’s all true. The Principality of Sealand is today considered one of the leaders of what is often referred to as the micronations movement. Micronations are countries which have been declared independent by individuals or small groups. In many cases such claims have been made on pieces of land, usually tiny islands. Since the internet got into full swing the traditional concept of micronations has evolved into cyber and digitally programmed territories too.

The principality of Sealand was the fruit of an error in judgement on behalf of the UK government. It had designed Roughs Tower (the sea fort) approximately 7 nautical miles from the coast, more than double the then applicable 3-mile range of territorial waters. Basically it had unwittingly located it in the international waters of the North Sea. While Roy Bates’ experience has been perhaps the best known (he’s fought off invaders from Germany and landed himself in a court case for fighting against the British navy—and won), his Sealand functions like many other micronations in that it has its own constitution, issues its own currency and provides its own passport.

Such is the evolution of the micronations movement and its growing popularity amongst a number of artists and musicians that the Sonar Advanced Music and Multi Media festival has this year decided to run the very first Universal Exhibition of Micronations.

Holding an exhibition of micronations would seem in keeping with a return to the festival’s roots—Sonar has always enjoyed positive critical and public responses when it’s dared to be at its most cutting edge. And in the case of micronations you might even say, eccentric.

Sealands’ micronation will be on display along with 4 quite different examples of the phenomena—Barcelona therapist Evru’s Evrugo Mental State, the multilayered kingdom of Elgaland-Vargaland, State of Sabotage from the creative label of the same name and NSK, A State in Time from the Slovenian industrial music collective Laibach.

Multimedias

Now in its 11th year, Sonar has over a decade grown from a small, almost underground electronic music festival with a few strands of multimedia thrown in to become one of Europe’s most prestigious multimedia events. Its music programming has in recent times attracted criticism for its growing commercial and conservative choices and the organisers appear to have listened by focusing this year’s line-up around the explosion of hip hop both in and out of Spain.

The festival’s multimedia arm though has strengthened considerably over the past 4 or 5 years and according to Andy Davies, the curator of Sonarcinema, that might very well reflect a changing of the guard between the mediums. “I certainly feel there’s a shift in the electronic music/electronic image thing,” says Davies. “It seems to me that there’s more interesting new things happening in the image side than the music side. And that’s a technological thing—now the technology is becoming more available for the image and quicker and cheaper—all the things that happened in the music. So there’s a whole lot of people coming to work in video that wouldn’t previously have had access to equipment. And for the same reason there’s this explosion of work that was originally there in the 90s in electronic music.”

The Sonarama section of this year’s festival as usual will put on show some of the latest developments in new sound and audiovisual creations, installations, software presentations and audiovisual concerts. A highlight this year is Thomas Koner’s Banlieue du Vide, at once a critique of the repressive possibilities of internet technology and a reflection on the passing of time. Koner’s work recently won the prestigious Ars Electronica’s Golden Nica award in the digital music category.

Switzerland’s Hektor, a suitcase containing among other things 2 electric motors, a spray can holder and a circuit board, and Canada’s Artificiel’s light installation Bulbes are also eagerly anticipated. Along with the media lab presentations displaying software and sound combinations, Sonar importantly continues to give a space to new creators.

Oscar Abril, Sonar’s Multimedia coordinator, says the event is still making a place for itself internationally: “Sonar is most definitely the main festival of its type in Spain and it certainly plays a defining role overseas even though you couldn’t classify it as an arts electronic festival. Nevertheless, it still retains that independent streak and belongs to a movement within a global movement.”

Like Abril, Sonarcinema’s Andy Davies has this year conjured up a film festival from a wide range of sources. It’s a neat mix of the original—Simon Pummell’s unscripted and wordless Bodysong documentary (with a soundtrack from Radiohead’s Johnny Greenwood) to the hysterical—Shynola’s computer animated adverts—to the retrospective—a showing of Ramon Coppola’s music videos that include Fatboy Slim’s Gangsta Trippin’, Moby’s Honey, Air’s Playground Love and Daft Punk’s Revolution 909.

In amongst that lot there will be a session on one of the pioneers of digital animation, Lillian Schwartz, and a menu of low budget electronic short films. To round it off there’s some very contemporary documentary takes on the hip hop scene in Venezuela as well as the punk and rap movements in Japan, China and India.

It’s this kind of visual social commentarist role that festivals like Sonar crucially play. “For me there’s places which produce a lot of interesting work and it’s surprising that should be so and I don’t really understand why it is,” ponders Davies. “Austria for example has fantastic video and visuals. Britain as well, there’s a lot of interesting stuff happening there, quite particular… Japan has a very particular take image-wise, especially graphically, so a lot of work that comes from there stands out. And I also think Finland is a very curious place. We show a lot of things from Finland!”

Davies believes it’s hard to get good local work to be shown in Sonar. He attributes that to a combination of cultural factors and a lack of investment from television and the state in experimental work or, for that matter, independent record companies who tend to finance low budget filmmakers in other parts of Europe. “One thing’s for sure. What makes a good public isn’t necessarily what makes a good creative environment.”

Sonar, Barcelona, June 17-19 www.sonar.es

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 51

© Michael Kessler; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

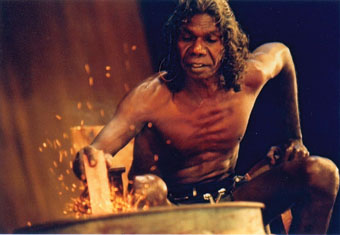

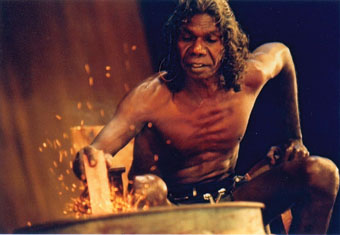

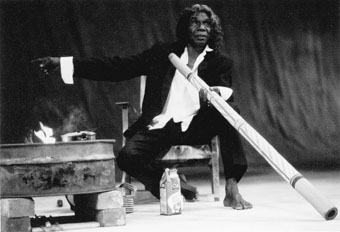

Morganics’ shows at Sydney Opera House’s The Studio and Brisbane’s Powerhouse are taking this hip hop virtuoso to a wider audience, recognition he fully deserves. He’s more often to be found in workshops for young people in regional areas, prisons and Aboriginal communities right around Australia and it’s that presence which frames and informs much of this solo outing. He plays it as if we are a group of young violent offenders in an institution participating in a hip hop workshop, teaching us beat-boxing and free-styling and demonstrating his moves: “this is about breaking, not entering.” He shows videos of his work, largely with Aboriginal youngsters, reflects on his hip hop beginnings as a kid (Circular Quay, 1984) and conjures a range of workshop experiences that reveal the pain of the lives of the people he teaches: teenage mothers, prostitutes, the dispossessed. As much as it’s a mission, Morganics’ journey is also an adventure, sometimes exhausting, as he crisscrosses the country, sometimes tense, as cross-cultural clashes loom. He recreates these moments with a vivid but laidback theatricality. It’s also a role model show. It’s hip hop evangelism with an Australian voice. It’s a critique of commercial hip hop (“I love it when I forget it’s a business”) and the sexism of the form, and satirical when it comes to record company and undergraduate responses to the art. And it’s a thrill when Morganics raps and dances: you just want more. His work with young Indigenous hip hoppers from Northern NSW is part of this year’s Message Sticks at the Opera House and will be reported in RT 62. The big question is will schools be able to use their $1600 pocket money from Johnny Howard’s 2004-5 federal budget to bring Morganics in to teach values? I hope so.

Morganics, Crouching B-Boy Hidden Dreadlocks, The Studio, Sydney Opera House, March 30-April 3

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 51

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

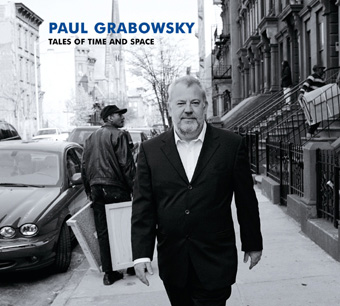

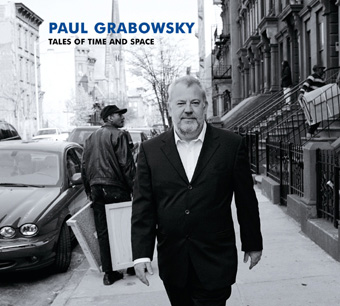

Tales of Time and Space, Paul Grabowsky

The CD cover photo says it all: Paul Grabowsky strolling around Manhattan looking very pleased to be there. And why wouldn’t he be, since he’s there to record 9 of his compositions with such top ranking American jazz musicians as Branford Marsalis, Joe Lovano, Ed Schuller and Jeff Tain Watts (although Marsalis, due to the dreaded ‘contractual obligations’, performs on only 2 tracks). Australian trumpet player Scott Tinkler jets in to complete the group. The sheer logistical effort of assembling these musicians in one time and place is no doubt a tale in itself, but the effort was worth it. This album is many things: a showcase of inventive compositions, a mix of styles and structures and a collection of uniformly excellent performances. Most of all, it is a statement of the possibilities of modern jazz.

The opening track Tailfin defines the album: highly ambitious, technically superb and a study in contrasts. At 9 and a half minutes, Tailfin is by turns blazing and meditative, yet it is the structure of the composition that leaves the final impression. It opens with a kinetic drum solo by Watts, played as if his mission is to compress as much dynamism as possible into 30 seconds. This serves as an opening statement for the album: beginning with a drum solo suggests the focus is to be on the compositions, not 88 keys and one ego.

Tailfin takes many surprise twists. Once the drums have settled down into the middle ground (Watts is never really in the background), a theme is played by Marsalis on soprano sax, accompanied by Tinkler on trumpet and toilet plunger (bought, according to the engaging album notes, from a Chelsea hardware store). This theme is a little disorienting: a fast vertiginous round that’s part folk dance and part Ornette Coleman. Once it’s done, Tinkler launches into an incendiary trumpet solo, backed only by the tumultuous drums. The trumpet is pure brazen energy, delivered in a clear tone that rides above and across the drumming. After this energy burst, the tune slows down, turning lyrical and reaching almost a still point. Grabowsky takes over the composition with melancholy piano lines, dropping to the lower register before stepping up to a chordal progression. This rhythmic development attracts the drums, which build up momentum again, this time summoning Marsalis. Now the composition is in a new phase, with Marsalis unwinding over drums and bass, while Grabowsky re-enters with those chords.

Marsalis takes the tune apart, in the decontructivist manner pioneered by Coltrane. Jack Kerouac described Miles’ bop trumpet as “speaking in long sentences like Marcel Proust”; Coltrane liked to play the same sentence over and over, from different angles until it was exhausted, an avant-garde re-writing of the Proustian sentence. This is what Marsalis does here, speaking one long soprano sentence upwards, downwards and sideways, building to a peak as the other musicians add their support. Then a return to the vertiginous theme, some stabs in unison like exclamation marks, and the trumpet trails off and upwards to end the composition. All this on the opening track: no wonder Marsalis cries “Great Caesar’s ghost!” when it’s over.

After this delirious ride, the album settles down a little but loses nothing in ambition. Tales of Time and Space is just that; a sweep across music history and cultural difference. Styles and methods are taken from a startlingly wide range of sources, from 17th century Spanish dance to Silverchair. But this is no postmodern pastiche. The various source materials are absorbed into Grabowsky’s jazz compositions, adding distinctive flavours but never spoiling the texture or status of the works. On a larger scale and at a different time, Duke Ellington did the same with his great compositions.

Sideshow Sarabande, the second track, is a jazz version of the Baroque triple-time dance, featuring Grabowsky in buoyant mood. Silverland is a sprightly tribute to the Aussie rock band, with bouncy piano, silvery trumpet, and a crescendo embracing the grunge-pop cadences of its inspiration. Angel is an overtly lyrical turn, featuring the album’s most beautiful melody. A collective commitment to simplicity allows the musicians to explore the lyricism while avoiding sentimentality, especially in the solos by Tinkler and Lovano on tenor sax.

The best—or at least most memorable—of the album’s tracks are these first 4; the second half of the CD does not quite match the first. Perhaps Grabowsky the pianist could have showcased himself on a solo or duet track to add formal variety. But these are minor quibbles. On this album the compositions and ensemble playing are the thing. The many times and spaces subsumed into this recording produce a here and now that is truly exciting to hear.

Paul Grabowsky, Tales of Time and Space, Warner CD 2004

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 52

© John Potts; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Given our everyday listening is spatial—the sound of the world is not in stereo, it’s 3 dimensional—it is interesting that its recreation through surround sound systems still seems a novelty. We are used to listening to our Dolby Surround Sound in cinema complexes, but it is still not standard sound event procedure to gather enough speakers and people with the techniques to perform live spatial audio mixes. So there was a degree of understated excitement about the evening at Lanfranchi’s Memorial Discotheque in Sydney’s Chippendale, featuring live surround sound performance by Sam Smith, Julian Knowles, Alex Davies and Melbourne duo Robin Fox and Anthony Pateras.

First up was Sam Smith, who has been appearing over the last year, as both sound and visual artist, but who is a relative newcomer to spatial audio. Smith’s soundscapes are luscious, featuring snippets of keyboard chords and broken melodies that drift in and out of focus, mixed with static sprays, tweaked harmonics and pulsing drones. He also blends in organic sounds, in this case the squeals and groans of children, perhaps, and grating metallic timbres. His spatialisation was intense, sometimes verging on the hyperactive, a temptation when you first discover the joy of pinging sounds around a room. It will be interesting to hear some more of his work when he has settled into the ideas and technology.

Julian Knowles is one of the undisputed masters of spatial audio, having worked in the area for many years before recent technology made it more accessible. Knowles’ sounds—the familiar palette of electronic hiss, click, crackle and drone—are so finely processed and sculpted that they take on new depths. His sense of composition is meticulous with an underlying tension, yet he never gets caught in the crisis of endless crescendo, instead shifting through different textural territories with fluidity, giving momentum and intensity to his work. What distinguishes Knowles from other artists is his restraint. He very rarely moves a whole sound, but sprays out elements of it. The effects play around you, frequencies swim while the core remains anchored. Knowles avoids the special-fx rollercoaster ride, preferring to work on a deeper psycho-acoustic level, expanding the sonic space of the room and creating a sphere of sound in which you are aware of every vibrating particle.

The initiator of the evening, Alex Davies, is well known for his interactive audiovisual installations so it was good to see him hone in on audio. Initially he showed a similar restraint to Knowles with a very slow accretion of details. Starting off with the organic sounds of voices, the work gradually developed into a beat piece with big bass and rhythmic glitch loops. Davies’ samples have a beautiful clarity, however some structural anomalies meant that the piece lacked cohesiveness, as we were often lead into zones that were not explored and then dropped. There is an interesting perceptual shift in spatialised audio when sounds are organic or completely synthetic. With organic samples there is a tendency to look for a ‘narrative’ cause and effect moving it closer to a cinematic experience, however when using digital sounds the placement becomes purely about the movement through space.

Restraint is not a word to be used when describing Melbourne’s Robin Fox and Anthony Pateras. Fox on laptop processing Pateras’ vocals and mixing desk emissions make for a fantastic aural assault. Facing each other like old men playing some demented card game they rupture the dominant trend of slow sustained works with pieces that are short abrasive bursts the length of rock songs. Each piece explores a different set of ideas. From Pateras there are snuffles, gurgles and belches, a bubbling cauldron of hisses and pops, bleeps and wild cries. Each of these textures is ripped apart and cellularly rearranged by Fox’s magic fingers creating sonic meteorites that burn brightly and disintegrate on entry. The works are so dense and fast that the spatialisation served merely to make the pieces twice as loud.

Fox and Pateras performed the same set 2 nights later at impermanent.audio in stereo, and nothing was lost with fewer speakers. In fact the multitude of speakers tended to separate the sound from the source, so that in stereo there was more of a visceral quality to Pateras’ cacophonic mouth clicks, lipsmacks and utterances, making the pieces, edgier and grittier. The piece based on kissing noises was particularly impressive in its uncomfortable over-amplified closeness. However even more impressive were the artists’ solos.

Robin Fox created a stir by bringing visuals into the well-defined audio only environment of impermanent.audio. (There have been 1 or 2 moments of visual stimulation previously but such things are generally not encouraged.) In Fox’s words his photosynthetic piece “explores the 1 to 1 relationship between sonic electricity and its effect on a single light photon excited across a phosphorous screen.” In other words his crafted oscillations make a little green dot grow and dance. The purity and fusion of the sound and visuals creates an interdependent realm that is at once mesmeric and invigorating.

Anthony Pateras performed a prepared piano improvisation on the already battered baby grand at the Frequency Lab. His approach to everything seems to be fast and furious, bashing at the keys to reveal all manner of timbres. Top notes rattle and vibrate like demented toys while bass notes thump and ominously thud. You hear the wood, the metal, the hammer, the pluck. Pateras plays a lot of notes…and then he doesn’t…letting a clanging chord ring out naked, carving silence out of chaos. A magnificent performance.

Fox and Pateras have just departed on a European tour, and it will not be long before they join Pimmon and Oren Ambarchi on the A-list of Australian sound exports taking the international scene by storm.

Sam Smith, Julian Knowles, Alex Davies, Robin Fox & Anthony Pateras, Lanfranchis Memorial Discotheque, April 2; Fox & Pateras, impermanent.audio, The Frequency Lab, April 4

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 52

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

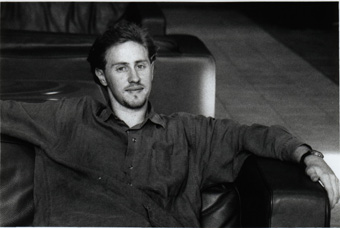

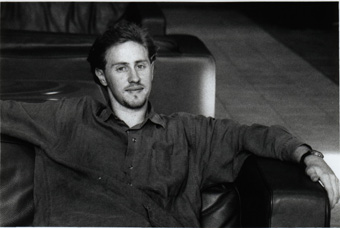

Damien Ricketson

photo Bridget Eliot

Damien Ricketson

Since 1995 Sydney-based Ensemble Offspring have been performing and commissioning new musical works. These new works are often presented in themed concerts alongside pieces written up to 80 years ago, highlighting some of the broad themes in recent music. Partch’s Bastards, for example, took up instrument building and alternative tunings, and other projects have centred on movements such as Parisian Spectralism and Polish Sonorism. This contextualising has an enriching effect, both in bringing out recent currents and ideas, and fostering new interpretative pathways within individual works. Offspring writer-in-residence Rachel Campbell talked to artistic director Damien Ricketson about the ensemble’s work.

Programming

At the core of the ensemble is a dedication to bringing out new material. A continual mission has been providing a platform, an outlet, for the aspirations of numerous young composers. This entails embracing risk in programming—the potential for failure is high but so too are the potential rewards, and some of these have been astounding.

The ensemble’s birth was an accident. Co-founder Matthew Shlomowitz and I, like any composers, just wanted a gig, a chance to hear our music. But we were able to seize on the enthusiasm of our performers to go on to promote fellow composers as well as countless seminal 20th century works that should also be heard.

It’s meaningful to draw new work into some kind of context, be it historical or just a broader, less parochial vision of contemporary Australian music. Profiling a key composer or theme and then drawing links to the activities occurring here and now helps to illuminate new material. Ideally we aim to present a new music event where the totality of the experience extends beyond the sum of its component parts.

Bozidar Kos

The forthcoming A Composer Profile—Bozidar Kos, Celebrating 70 Years features chamber music by Bozidar and by younger composers who have been his students at the Sydney Conservatorium. A particular highlight will be the world premiere of Fatamorgana, especially commissioned for the event.

Bozidar is a composer with an eye for detail, his works are like well-crafted gems—the more you go into them, the more you appreciate their depth and refinement. His music draws upon a raft of influences ranging from the French Spectralist tradition to his own jazz and folk heritage. His eye for detail also made him a highly respected educator. To this day, the best composition lesson I ever had was when he once tore strips off me.

We also have the world premiere of a piece by English composer Michael Finnissy dedicated to the ensemble’s co-founder Matthew Shlomowitz. In our postmodern milieu he is one of a few composers drawing tangible references to other musics in strange and wonderful ways. There are emotive extremes—he’s a new and different kind of romantic.

Philip Glass

The Philip Glass we’re performing in Concert 2, 2004: Art of Glass is the early stuff. This is the pre-Einstein on the Beach experimental process music from a period when the composer was little known outside of a small New York loft scene and his music was a profound alternative to Euro-modernism.

Over the years, as Minimalism has become more style than concept, the term has become something of a conservative war-cry. In this concert we hope to recapture the bold experimental aesthetic that underpins the music’s origins. This is music stripped to its bare essentials, mechanical patterns repeated again and again. It will either irritate the hell out of people or induce a wonderful hypnotic state of listening. Philip Glass has authorised us to perform these works usually reserved for his own ensemble. We find ourselves in the curious position of being the first band outside the Philip Glass Ensemble to perform works such as Music In Fifths.

There’s also a piece I’ve been working on with Melbourne poet Christopher Wallace-Crabbe whom I met on residence at Bundanon. The work, A Line Has Two, is a spacious meditation on time and impermanence. Temporal references pervade the music’s structure, drawing a boundary between the familiar and the unfamiliar, from citations of Strauss and Mahler to exotic instrumentation such as the Tusut, an ancient Arabic glass instrument, and the ancient Greek aulos.

International

We have an invitation to play at the World Music Days in Croatia next year. And last year we toured Europe as guests of the Warsaw Autumn Festival. We performed in London, Amsterdam, Krakow and Warsaw, and the festival commissioned my Trace Elements which will receive its Australian première in the Bozidar Kos concert.

At Warsaw we had a packed auditorium of over 300 people. The reviews were good and the standard of playing was commented on a lot—especially encouraging given that we were performing back to back with some of Europe’s leading new music specialists such as MusikFabrik.

The Future of New Music

I think the more experimental end of the spectrum will always cycle between a more peripheral and more central role in the creation of new classical music. We’ve had a very conservative decade or 2 but I am encouraged by signs of a renaissance of interest in musical alternatives to the mainstay classical staples. When I was talking with the artistic director of the Warsaw Autumn, he felt they went from the radical 60s to a very conservative position at the end of the century and now their audiences were back in the mood for something a little more challenging. Encouragingly, this demand is not coming from old die-hard modernists, but from the young generation. Indeed, over half the audience at our Warsaw concert were under the age of 30.

Ultimately I am a long-term optimist. I keep the flame alive. I genuinely believe that there is a new ‘new music’ and it will have its place enriching the art-music tradition of the future. The possibility of a novel, original sonic experience that has a profound emotive effect is still very much alive and apparent.

A Composer Profile—Bozidar Kos, Ensemble Offspring; Sydney Conservatorium of Music, July 4; Art of Glass, Ensemble Offspring; The Studio, Sydney Opera House, July 29, www.newmusicnetwork.com.au/ ensoffspring

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 53

© Rachel Kent; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

![Isorhythmos, Un/Cage[d] Version 1.1](https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/10/1054_mccoombe.jpg)

Isorhythmos, Un/Cage[d] Version 1.1

photo Chris Osborne

Isorhythmos, Un/Cage[d] Version 1.1

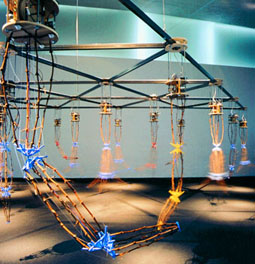

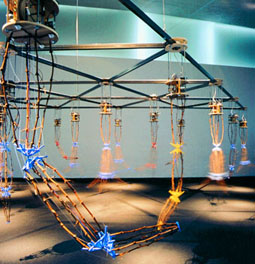

Un/Cage[d] Version 1.1 was the latest live offering from Brisbane-based percussion ensemble Isorhythmos. The title gives a clue to the creative impetus behind the event: the words, music and ideas of John Cage providing the performance’s conceptual framework. The show was interspersed with recitations of texts by Cage and Gertrude Stein (a kindred spirit and influence on the composer). These effectively functioned as a structural and theatrical device during transitions, shifting the focus from energetic ensemble playing to the whimsical, obscure and profound words from these sages of 20th century art and thought. The characteristic ‘stream of consciousness’ approach and poetic deftness of both Cage and Stein set the pace for a performance that was rarely predictable and often surprising.

Cage’s Living Room Music for percussion and speech quartet (with text by Gertrude Stein) opened the performance. Members of Isorhythmos eased on to stage and made themselves comfortable in a make-shift lounge set up behind the main performance space. True to Cage events, the audience were disconcerted. “Has it started?” “Should we listen?” “Should we keep talking?” And then the music commenced. Clever speech rhythms, tightly rehearsed, soon had all of us enthralled.

Gerard Brophy’s Songo, a percussion composition influenced by Cuban drumming rhythm and style, was performed with great energy, precision and joy, the structure of the work allowing for high levels of interaction and improvisation among the players.

Guest artists Topology joined forces with Isorhythmos for Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm (Bartok arranged by David Montgomery) and the wittily titled Six Bulges in Dancerian Rhythm composed by Montgomery. The Six Dances, originally composed as piano studies for Bartok’s son Peter, were transformed into something altogether different, fleshed out and rendered in Technicolour through Montgomery’s arrangements.

Six Bulges represented something of a world tour of drumming traditions: West African, Brazilian, Senegalese, Turkish, Cuban and jazz styles all got an airing. Montgomery’s very clever creation of an ‘uber’ work gave Isorhythmos and Topology ample opportunity to show off their considerable talents. High energy performing alternated with moments of calm and delicacy, skilfully demonstrating the range of this 8 piece percussion ensemble.

Although it was difficult to pick one highlight, the performance of Toru Takemitsu’s Rain Tree was stunning. The text on which the piece was based, Kenzaburo Oé’s poem The Ingenious Raintree, was projected on the overhead screen. Even without the text, the piece is mesmerisingly beautiful. The keyboard percussion and especially the vibraphone with the added quality of crotales created a delicate shimmer and resonant raindrops of sound. Isorhythmos’ attention to detail and subtlety, the careful shading and interaction between parts and the precision of their playing reflected a ‘chamber music’ aesthetic in the best sense of the term.

The final work for the evening, Imago (Montgomery/Scholes/traditional) was another large scale multi-section piece designed to showcase the talents of Isorhythmos and Topology. Once again the strong influence of West African drumming was present, the work incorporating a mix of rhythmic cells and motifs. There were some very effective sound gestures, utilising the spacing of the performers to create waves of sound moving around the semicircle of drummers. Having sat comfortably in the ‘living room’ at the rear of the stage, Topology returned to the main performance space and joined with Isorhythmos for the final section of Imago. After an extended piece of drumming, Topology’s line up (strings, sax and piano) was a welcome addition to the sound world, with some lovely spots for soprano sax and viola woven into the piece. Imago was perhaps a little on the long side, diverging from the formula of carefully paced material that characterised the rest of the evening.

The audience’s enthusiastic applause at the end of the performance confirmed that Isorhythmos are doing something right. They are attracting large audiences to contemporary music and keeping them entertained, not just through their considerable skill as musicians, but also through the enthusiasm and imagination with which they present the music.

Isorhythmos, Un/Cage[d] Version 1.1, guest artists Topology; Brisbane Powerhouse, March 26-27

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 54

© Christine McCombe; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

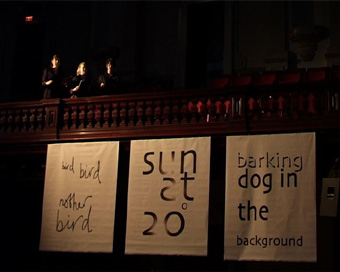

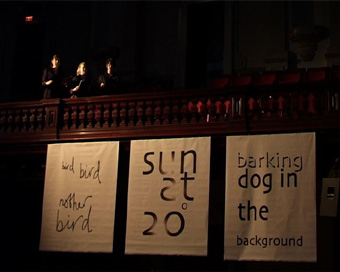

Song Company, 14; artwork Lee Paterson

photo Finton Mahoney

Song Company, 14; artwork Lee Paterson

It’s not blood, it’s metres of colour splashed wide across the floor, rich red, yellow and blue, thick and waxy (Mark Titmarsh, installation) as if just cooled and come to rest. We gather round it for the sung whoops and cries and expressive double bass patterning of Raffaele Marcellino’s Via Dolorosa 1 (1993) for Station 1, Jesus is condemned to death. It’s Good Friday night in Sydney Town Hall and a large crowd has gathered for 14, a once regular musical and visual art collaboration resurrected from its last appearance at the MCA in 1993, the source date for most of the compositions for this program (unless otherwise indicated), but accompanied by 2004 art works.

We wander into Centennial Hall on the next stage of an engrossing joumey, reflecting on the power of one’s belief or the efficacy of myth for others; art is the means here. Directors Neil Simpson and Roland Peelman put the hall to excellent use, constantly shifting us and our perspective: we’re on the stage, up in the balcony, out in the ante-rooms, each area distinctively and evocatively lit, the main hall often radically transformed. Voices descend on us from above or speak to each other across the hall. Between compositions and showings, David Drury improvises with a fine sense of mystery and awe on the Town Hall organ.

The correspondence between music and visual art is variable, from lucid to opaque, with the compositions just long enough to reflect on possible connections. To Andrew Schultz’s beautifully fluent soprano duet, Silk, Michael Hutak releases a slow shower of small black papers from the high ceiling, worded “Every man for himself. Go back to your homes” (Station 2, Jesus bears his cross). Lee Paterson’s banner (“bird/mother/sun at 20 degrees/barking dog in the background”) obliquely but suggestively accompanies Moya Henderson’s “Now Madness Half Shadows my Soul” (2004) for Station 4, Jesus meets his Holy Mother. A sublime trio of female voices meets a male voice from across the hall above us.

For station 5 (Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus), Michael Whaites, lying on a bed of straw fringed with leaves, patiently loads bricks onto his body to Stephen Cronin’s grimly expressive Bright and Black Blood. A gagged Lucy Young is immersed in a tank of water (labelled “Absolution”) which is served to us in small cups by a helper, for Jesus meets St Veronica (Station 6), to Andrew Ford’s Palindrome. To Edward Cowie’s The Third Stumble (Station 9), Ana Wojak in high-booted military attire tugs at a cruel leash hooked into the back of a woman in red with sewn lips (Fiona MacGregor).

For the premiere of Elena Kats-Chernin’s Golyi (2004, to Les Murray’s A Study of the Nude), we gather in a long corridor where Kate Champion projects an image of Christ onto a surface that she tears at to reveal a blue sky and a red sun as Kats-Chernin’s music marches on with Prokofievan inevitabilty, all pain and beauty. Hobart (John) Hughes gathers us on the stage for Station 11 where he’s angled his projector to a screen with a Christ mask which he floods with rapidly morphing, surrounding imagery, creating a kind of furious timelessness, an animated Sydney-Nolan-does-Christ, finally focusing on the face so that it seems to come alive.

The sense of occasion and mystery is heightened at Sation 13 (Jesus is taken down from the cross) by Mary Finsterer’s remarkable Omaggio all pieta (video by Dean Golja) with its rich dramaturgy of voices nasal and guttural evoking some primal, quite foreign Christianity. With 14’s suggestive pairings of artworks and music, and the Song Company in superb voice and a wonderful set of spatial transformations, you didn’t need to be a believer to be moved.

The Song Company, 14: 14 Stations of the Cross, directors Roland Peelman, Neil Simpson; Sydney Town Hall, April 9

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 54

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Flood

photo E. Matejowsky

The Flood

Noah’s job of getting pairs of the world’s animals onto the ark must have been a whole lot easier than moving some 1000 people through the streets of Lismore for the final night of NORPA’s The Flood. What could have been an effective tale soon became a distended epic, far removed from the economy of the comic Noah’s Flood of the great mediaeval English Mystery Cycles. But once we got to the riverside for the final act things looked up and that’s where most of the music happened with a small but very effective big band.