Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

<img src="http://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/3/361_ndalianis_eyes.jpg" alt="David Lawrey & Jaki Middleton,

The Sound Before You Make It (2005),

kinetic installation with strobe lighting and audio”>

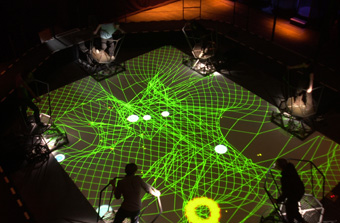

David Lawrey & Jaki Middleton,

The Sound Before You Make It (2005),

kinetic installation with strobe lighting and audio

courtesy of the artists

David Lawrey & Jaki Middleton,

The Sound Before You Make It (2005),

kinetic installation with strobe lighting and audio

DEVELOPED FROM THE EXHIBITION HELD AT THE HAYWARD GALLERY, LONDON (2004-5), EYES, LIES & ILLUSIONS AT THE AUSTRALIAN CENTRE FOR THE MOVING IMAGE CONTAINS MORE THAN 500 BOOKS, PRINTS, OPTICAL INSTRUMENTS AND TECHNOLOGICAL WONDERS THAT ARE DRAWN FROM THE WERNER NEKES COLLECTION (MULHEIM-AM-RUHR, GERMANY).

This extraordinary collection began in the mid-1960s when Nekes, a German experimental filmmaker and professor in film studies, started collecting examples of optical phenomena as teaching aids that highlighted pre-cinematic history. The objects, however, developed a mind of their own and grew beyond their pre-cinematic agenda into an encyclopaedic collection that now comprises approximately 25,000 devices devoted to the history of optical technologies.

If the Nekes collection can be understood as a contemporary wunderkammer that encases a micro-history of pre-20th century visual media technologies, then Eyes, Lies & Illusion might be seen as a micro-micro-history. Cameras obscura, magic lanterns, praxinoscopes, peep-boxes, daguerreotypes, kinetoscopes, panoramas and anamorphic lenses populate the appropriately darkened lower bowels of the ACMI building at Federation Square. The most impressive feature of this exhibition is that it represents a pansemiotic logic: each object is endowed with multiple layers of signification that speak of the past, the present and the present’s relationship to the past.

The exhibition is divided into seven thematic sections. Shadowplay, Tricks of the Light, Riddles of Perspective, Enhancing the Eye, Deceiving the Mind, Persistence of Vision and Moving in Time all introduce the audience to a gamut of spectacles, wonders of science and the technologies that create them: puppets, shadow theatres and magic lanterns manipulate light and dark to produce wonders that delight; prisms, lenses, mirrors and kaleidoscopes distort and alter light to reveal its mysterious properties; truly enchanting dioramas, panoramas, perspective boxes and a walk-in, distorting Ames Room all make concrete the mathematical principles of perspective; cameras obscura, scientific studies on anatomy, microscopy and astronomy, and examples of early photography reveal the way optics and technological innovation made visible the previously invisible; anamorphic images, visual cryptograms and optical illusions show how the human eye can succumb to artificially produced tricks of the eye; the wondrous motions of phenakistoscopes, zoetropes and praxinoscopes appear to magically create animated worlds; and pioneering experiments in photography and the cinema capture indexical reality opening the way to a new generation of optical illusions.

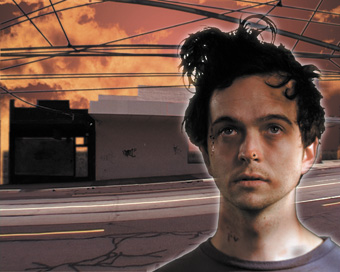

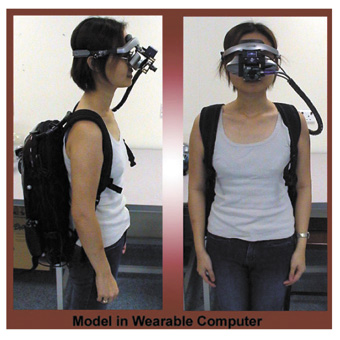

Teasing its audience with a rich, engaging and entertaining history of technological inventions that enhance and deceive human vision and perception, Eyes, Lies and Illusions typifies the active relations that many of these technologies command of their viewer-participant. The exhibition demonstrates the continuity of interest that has persisted in using media, in particular entertainment media, to push the boundaries of technology and vision, art and science through centuries. A pair of Florentine works painted on the natural stone known as pietre paesina (1620) depicts battle scenes and crumbling castles. Here, nature and art collide. In places, the natural patterns created by the stone’s surface portray smoke and crumbling castle walls; in other places, the artist’s hand takes over to depict the same subject matter. The eye is deceived. Where does nature end and human artifice take over? Perspective boxes and dioramas invite the participant to peep into their initially concealed spaces in order to discover alternate, virtual landscapes, theatrical performances and seascapes. Transparent pictures and Chinese shadow theatres transform their dark, two dimensional spaces into brightly lit, marvellous three-dimensional worlds. And in one of the 12 contemporary works, The Sound Before you Make It (2005), a kinetic installation with strobe lighting by the Australian artists David Lawrey and Jaki Middleton, the phenakistoscope’s reliance on the phenomenon of persistence of vision is given a new context as amused viewers watch small and static Michael Jackson figurines succumb to motion as the merry-go-round disc they stand on swings around and around to the rhythm of “Thriller.” The arrangement of all these objects serves to build visual (and audio) bridges that emphasize the playfulness of nature through the associative powers of sight.

Significantly, the experience of this exhibition reveals how no media are ever divorced from history. The camera obscura, for example, reveals its connections with the later invention of photography. The eerie 3D stereoscopic image of the filmmaker Lumiere reveals its connections to the spatially layered but illustrated 3D spaces of the dioramas. Marey’s chronoscope experiments expose themselves as predecessors of the digital animations used in current film effects—a fact also stressed in Carsten Höller’s 1998 work, Punkterfilm, which similarly maps a geometric depiction of movement. And perspective instruments, treatises and the objects that reflected its laws—dioramas, panoramas, and perspective boxes—reveal how they have found a new form of expression in the boxed screens that contain the virtual architecture of computer game spaces. But these objects are so much more than examples that highlight the path that eventually led to the diverse media of our own times. Almost every technological apparatus or depiction of wondrous media in action within this show shines independently of the role it serves as predecessor to a later media format.

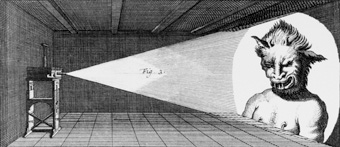

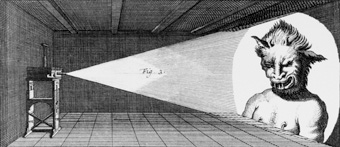

The magic lantern is a case in point: walking through the show, the captivating properties of the optical devices have the capacity to ensnare the viewer with their mesmerising powers. It’s easy to forget the complex historical and cultural contexts that nurtured the production of these technologies and the modes of perception they evoked. As the concise and informative exhibition labels explain, and as is made even clearer in the excellent exhibition catalogue, the initial popularity of the magic lantern as visual entertainment has its origins in the 17th century. Athanasius Kircher, baroque scholar and scientist of encyclopedic proportions and the individual often (incorrectly) credited with the magic lantern’s invention, discusses its function and outlines his observations and experiments in light and shadow in his book Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae of 1646 and in Physiologia Kircheriana Experimentalis of 1680, which is represented in the exhibition. Through their entertaining properties, these optical devices expressed the ways in which contemporary ‘science’ had altered perceptions of the universe.

The examples of magic lanterns range from simple, hand carved wooden boxes with lenses, to highly crafted metallic exteriors that depict the Eiffel Tower—all works of art in their own right. The sensory impact of the exterior designs further extends to the capabilities of the interior mechanics: a projection of H McAllister’s magic lantern slide of a dancing skeleton (c.1880), which was filmed by Nekes as part of his Media Magica film series (snippets of which are projected throughout the exhibition and successfully visualise many of the technologies in motion), drives home the fantastic and entertaining nature of the objects. Yet, the magical properties of these boxes are found not only in their well-crafted exteriors and the illusionist possibilities that this technology is capable of, but the micro-historical role they served. The various lithographs, prints and books from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries accentuate this by providing snippets from time past: the image of a magic lantern projecting an image of a demon, for example, is from Gulielmo Jacobo ’s Gravesande’s two-volume book, Physices Elementa Mathematica (1748). As one of the earliest and most influential followers of Newtonian philosophy in Europe, ’s Gravesande’s image of the demon projection, and the accompanying image that reveals the interior mechanics of the magic lantern, visualised the theory of optics and light. A fantastic subject matter served a rational and scientific purpose that speaks of the arrival of the era of Enlightenment. Throughout its history, the magic lantern both enchanted and reflexively drew attention to the more rational function that these public spectacles served as scientific explorations of modes of perception, and of how the human eye is capable of being deceived through technological means. The books and prints in the collection play a significant role in highlighting the context of display; the magic lanterns the method and rationale of reception.

One of the most dramatic examples of this is the display of the frontispiece of Étienne-Gaspard Robert’s Mémoires Récréatives Scientifiques (1831), which depicts one of his famous phantasmagoria lantern projections. Better known as Robertson, he was a Belgian inventor, physicist and student of optics who improved the technology of the magic lantern, including its capacity to enlarge and decrease images. Robertson performed his most infamous show in Paris in an abandoned chapel surrounded by tombs. Crowds flocked to the dimly lit graveyard to experience (initially concealed) magic lantern effects of flying skulls and ghoulish apparitions against the backdrop of creepy lighting and sound effects. While it isn’t clear whether the frontispiece depicts this performance, the participants in the event, nevertheless, respond in similar ways by fainting, screaming and running away from the horrors that appear before them. Yet, despite the centrality of illusion and the theatrical emphasis on the fantastic, Robertson’s intentions were also scientifically motivated. His application of the magic lantern reflected Enlightenment concerns with scientific rationalism; reason and a scientific approach to the world could, it was believed, arm the individual with answers to the most fantastic and irrational of problems. Exposing his methods after the ghostly spectacle, Robertson’s aim was to arm the audience with scientific reason by showing them the technological and scientific means by which he conjured his illusions: the fantastic was a deception controlled by technological means.

For these magicians and popular scientists, there was nothing science and technology could not explain or achieve. But as commentators like Octave Mannoni, who contributes one of the chapters in the exhibition catalogue, has explained, and as those who experience this exhibition clearly understand, having insight into the means of the illusion’s production—its trick—exposed and explained through rational means and scientific process doesn’t make that illusion any less astounding. If only to experience this state of bizarre ambivalence, it is well worth visiting this fascinating and, in many respects, ground-breaking, exhibition.

Eyes, Lies & Illusions, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Nov 2, 2006-Feb 11, 2007

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 pg. 21

© Angela Ndalianis; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

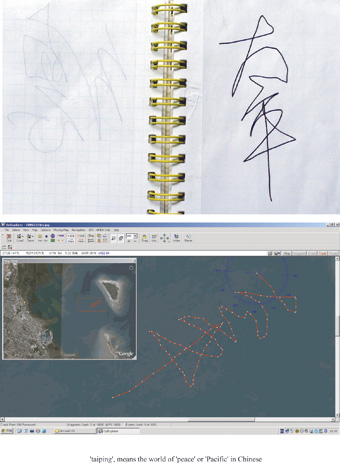

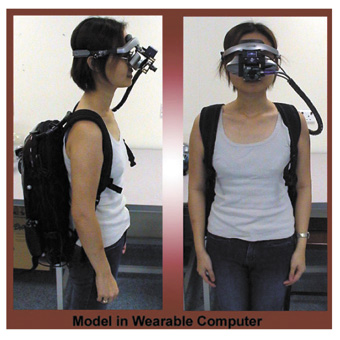

THE IMAGE, FRAMED AND HUNG TO CATCH THE EYE AS ONE FIRST ENTERS THE GALLERY, IS A SUITABLY CHARACTERISTIC ONE: DYNAMIC IN COMPOSITION AND TONE, WITH AN INKY FLUIDITY TO ITS LINE, IT SEEMS AT ONCE BOTH ORGANIC AND FUTURISTIC, NOT TO MENTION KIND OF CUTE. IN IT, ASTRO BOY, THAT ICONIC AND SPRIGHTLY BOY CHILD ROBOT WHO FOR DECADES NOW HAS SERVED AS THE AVATAR OF JAPANESE ANIME AND MANGA IN THE WEST, IS FIGHTING A GOOFY LOOKING HUMAN ADULT, WHOSE EXPRESSION OF BEWILDERED ASTONISHMENT CAN BE GLIMPSED AS HIS SINEWY BODY SOMERSAULTS BACKWARDS THROUGH THE AIR, SOUNDLY PUMMELED AND CLEARLY BEATEN.

<img src="http://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/3/374_clayfield_tezuka_black.jpg" alt="Tezuka, Black Jack, cover from Black Jack, 1974,

Weekly Shonen Champion, published by Akita Shoten”>

Tezuka, Black Jack, cover from Black Jack, 1974,

Weekly Shonen Champion, published by Akita Shoten

©Tezuka Productions

Tezuka, Black Jack, cover from Black Jack, 1974,

Weekly Shonen Champion, published by Akita Shoten

The exhibition in which this image appears, Tezuka: The Marvel of Manga, is full of such visually striking images. Developed by and for the National Gallery of Victoria in collaboration with guest curator Philip Brophy, and touring to both the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, and the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, in 2007, the exhibition marks the first Western retrospective of the work of pioneering manga artist and innovator Osamu Tezuka, creator not only of Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion (aka Jungle Emperor), but of over 700 other manga titles. Not all of these are represented in the exhibition, of course, but those that are (about sixteen titles) are not only representative of the remarkable breadth and depth of Tezuka’s oeuvre—not to mention its quasi-philosophical richness and inherent humanistic worldview—but also clearly establish him as one of the finest graphic artists of the post-war period, artist, entertainer or otherwise.

For the Western viewer, the iconic figure of Astro Boy serves as a convenient entry point into the world of both manga and Tezuka. I am no exception. Like many of my generation, my only previous connection to Tezuka was watching Astro Boy on television back when I was a little kid. His spiky black hair and his rocket booster boots are instantly recognisable but my interest in this sucker punch of an image—and in the exhibition waiting beyond it—has less to do with my childhood memories of serialised early morning cartoons than it does with the image’s graphic power, which is like a black-and-white slap in the face.

Tezuka’s work pivots on a series of dichotomies. The most obvious of these is the not-quite-absolute split between his manga for children and his gekiga for adults, embodied in the exhibition space itself by the colour-coded division between green walls (children’s manga) and blue (adults’ gekiga). However, this is by no means the only or the most interesting dichotomy. There is also the divide—a certain graphic tension—between abstraction and figuration, which often manifests as a struggle between page layout and panel content, or, within the panels themselves, between background and foreground (Tezuka’s backgrounds are like Futurist Florence Broadhurst wallpapers, particularly in a manga like Astro Boy).

There’s also a tension between modes—one might even say ‘schools’—of visual representation; a tension which cuts across all the manga and gekiga appearing in the exhibition. At times, Tezuka’s work seems to strive towards a kind of no-nonsense (if certainly heightened) realism; at others, it embraces no-holds-barred abstraction, Impressionism, or my personal favourite, Surrealism.

There are panels (and whole pages) in some of Tezuka’s darker gekiga work, particularly Bomba and Eulogy for Kirihito, which shock with their surrealist imagery. In a page from the latter, to illustrate Kirihito’s mental and physical torment as he transforms into a hybrid creature—half-dog, half-man—Tezuka gives us a series of disparate, terrible images, motivated not by any narrative or diegetic causality, but by a kind of emphatic, affective causality. The image of a primitive, almost totem- or sculpture-like being, lying on its back against a solid black background screaming, is genuinely terrifying (indeed, it was one of a few images that, for its very strangeness and uniqueness within the context of the exhibition, I just had to go back and see for a second time before I left). Other panels on the same page show a solid black form in the shape of an explosion and the turbulent surface of a pond during a downpour.

In another image from Kirihito a doctor, in a hospital somewhere, comes to a shocking realisation about something or other. Presently, his glasses begin to levitate, floating away from his face, which fades away. The floating spectacles instantly recall the floating bowler hats of Hans Richter. Rising against an empty white background, the spectacle lenses suddenly crack. Blood pours out into the air from invisible eye sockets. And then we’re back in the hospital again, in reality, ready to get on with the story.

But this page appears in a frame, behind glass: there’s no story to get on with. The images are abstracted, fragmented, devoid (even robbed) of their narrative context. Continually, we are told—by the wall panels, by the room book, by the small army of tour guides who lurk behind corners waiting to jump out and inform you—that Tezuka’s manga is concerned, first and foremost, with the telling of a story. But in the context of the gallery space, where comic books are hung as opposed to held, fingered, dog-eared and read, manga-stories become—(gasp!)—graphic art and, as such, at least comparatively, storyless.

And so as I leave this visually exhilarating exhibition, feeling genuinely excited about all that I have seen, I am hit all of a sudden by a feeling that I’ve missed something. I begin to wonder if I really know any more about manga than before. I wonder if I know less. I realise I want to turn the page and to find out what happens to Astro. The visual dynamism of his movements seems less important to me now. A gallery wall is not a comic book. I want to know what happens next.

Tezuka, the Marvel of Manga, curator Philip Brophy, National Gallery of Victoria, Nov 3-Jan 28; Art Gallery of New South Wales, Feb 23-April 29; Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, June 2-Sept 9

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 pg. 22

© Matthew Clayfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

THE DIVIDE BETWEEN THE MARKET SECTION OF THE AUSTRALIAN INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTARY CONFERENCE WHERE PRODUCERS PITCH PROJECTS, AND THE CONFERENCE SECTION THAT FOCUSES ON THE CRAFT OF MAKING THE DOCUMENTARY IS BECOMING INCREASINGLY CONTENTIOUS. THE NEW CONFERENCE DIRECTOR HAS EVEN ENSURED THAT THE TWO STRANDS NOW OCCUR IN SEPARATE SPACES.

The Socialist, The Architect and the Twisted Tower

For the last few years the award-winning Adelaide filmmaker Heather Croall (now Festival Director, Sheffield Docfest, UK) ran the event. She brought to AIDC an internationalism, a slickness and an ongoing commitment to maintaining the craft section of the conference. The new director Joost den Hartog comes from the market side of documentary events. He has organised markets at, among others, Amsterdam’s IDFA, Toronto’s Hot Docs and our very own AIDC. His appointment represents a shift in dynamics for AIDC.

English is not den Hartog’s first language and he has the diplomatic considered speech patterns of a person who is not a native speaker. He is fast to assure me that non-market sections of the conference are still important. “The marketplace is an important part of the conference but that is not the flagship or the main focus. The main focus this year, because we are celebrating AIDC’s 20th anniversary, is on motivation and inspiration and trying to find answers for questions like, ‘What is the purpose of documentary for society?’.”

The ‘conference’ sessions from the programme profiled on the AIDC website are almost all market related and aimed at producers. These sessions are the traditional territory of directors, writers, editors and cinematographers. Documentary directors and writers may mutter under their breath about keeping the craft sessions but den Hartog is actually catering to his market by doing this. Documentary filmmakers have voted with their feet at previous conferences, turning out in droves to anything about potential financial resources. In a sense the ‘conference’ sessions for the directors et al had almost become sideshow to keep them entertained whilst their producers ran around like mad chooks cornering funders and TV execs.

The final session is where the large question “Can Documentaries Change the World?” will be posed. Ross Kauffman, one half of the directorial team of Born Into Brothels: Calcutta’s Red Light Kids (2004), will talk with Variety film critic Richard Kuipers to try to find an answer. The question implies functionality as fundamental for the documentary form. It turns out den Hartog does indeed like documentary to have a function, “Call me a hippy or naive, but I think documentary is a very powerful way to raise awareness and to actually mobilise behavioural change and establish social change in society. I am very convinced of that. And I think that there are plenty of examples of recent films that have been able to do that…The most obviously example is An Inconvenient Truth. Now even John Howard thinks that there is something like global warming going on. It is quite an achievement for a filmmaker to get to John Howard.”

Unfortunately it looks likely that Participant Productions’ Diane Weyermann will be unable to attend the conference, because she’ll be busy glamming up for the Oscars where An Inconvenient Truth (2006) is nominated. However Participant Productions is a company well worth watching. Started by the eBay billionaire Jeff Skoll, it aims to fund films that have a social change agenda and turn them into films that will have broad appeal. The company’s tagline is, ‘Lights, camera…social action!’

One of the interesting side effects of the market people taking over conferences is that they have created a space in which filmmakers might start thinking creatively about the marketplace. Joost says, “On the Monday of the conference there are two sessions designed to explore an alternative marketplace by looking at the example of the internet and starting to look at relationships between various platforms. It will also look at other potential financiers like NGOs. DocAgora is an international initiative which had its first gathering in Amsterdam.” There are DocAgora sessions planned for a number of conferences around the world. (DocAgora describes itself as “a virtual webplex” for documentary: “an open space to consider new forms, new platforms and new ways of financing creative, authored and socially engaged documentary content. www.docagora.org). Joost continues, “A report will be written of all the sessions and eventually it will have to result in an alternative marketplace that can exist next to the traditional broadcast model.”

Whilst on the subject of commissioning editors, an embarrassing moment occurred last conference when the search for a commissioning editor during a pitching session resulted in a speakerphone admission that she was at the beach. It’s a worrying notion that buyers might see AIDC as a beachside break. Joost says, “We screen all buyers on their willingness to work with Australians and Australian content. And the reason why they come is that they are interested in Australian content or have a willingness to work with Australian producers. We do a follow-up every year after the conference to see what kind of deals are made. Most of them go home with two or three presales and a bunch of contracts and projects in development.”

A large contingent from Asia will be attending AIDC this year. Joost says “We have quite a big involvement from Discovery Asia and [they] will announce a scheme which is new. They have given their Australian office a fund to commission Australian content. It will be spread over two years for the Australian independent sector.”

When asked about what he thinks are the current crises in documentary den Hartog mentioned the obvious, not enough funding, but also felt, “the broadcasters are in a more competitive market these days and they want to brand their channels. That has consequences for independent producers and on the type of content that [the broadcasters] acquire.” The issue of branding will be covered at the conference at Rudy Buttignol’s session, called “It’s the Flow Not the Show.” (Buttingol is a leading Canadian network commissioner and programmer). It promises to be an interesting session considering the traditional notion that documentary is about ‘program strands’ and that individual 50 minute works are fast giving way to reality style series in Australia.

Australian International Documentary Conference, Adelaide, Feb 23-26, 2007, www.aidc.com.au

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 pg. 20

© Catherine Gough-Brady; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

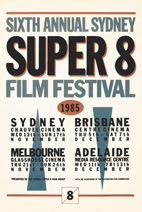

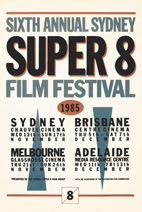

SUPER 8 HAS HAD A RESURGENCE OF LATE WITH SYN CITY AT THE ACP AS WELL AS SUPER 8 SCREENINGS AT THE CHAUVEL CINEMA. BOTH SHOWS WERE PART OF D/LUX/MEDIA/ARTS’ 25TH ANNIVERSARY THAT ALSO SAW THE LAUNCHING OF D/ARCHIVE.

Posters, Sydney Super 8 Film Group

Courtesy D/Lux/Media/Arts

Posters, Sydney Super 8 Film Group

As part of the archive project I interviewed Kate Richards, who set up the first two Super 8 festivals, and Mark Titmarsh, who was instrumental in the formation of the Sydney Super 8 Film Group later to become Sydney Intermedia Network and finally d/Lux/Media/Arts.

Kate, you initiated the first Super 8 film festival with Deb Collins. Your background was a distinctively Sydney 80s mixture of politics, squats and French cultural theory?

KR We both began shooting Super 8 while still in high school, and were very political young people and strong feminists. In 1980, when we established the first Super 8 film festival we were living in the Surrey Street squats…Our imperative was just the politics of getting this stuff up on screen. Deb approached the Sydney Filmmakers Co-op to put the work on. She talked them through their initial response of, ‘Oh Super 8, that is not a valid format.’ They were media makers, content and documentary orientated, and artisanal based. What we represented were the new wave of the tertiary-educated, French theory driven students from UTS. Further down the track I could see that without a strong studio practice the whole thing falls over.

How did the first festival go?

KR It was an unbelievable success. We made a little poster and we photocopied it and just stuck it around in cafés and on posts and people had to mail their work in. We got a huge amount of films and we showed them all. The program was very long and we packed out the Co-op the whole weekend. The Co-op were astounded as they had a lot of trouble getting bums on seats. I think the festivals captured a moment when a whole lot of new forms of aesthetics and signification were starting to bubble away—classic post modernity before the term was being used in Sydney—films such as Stephen Harrop’s Square Bashing, with found footage re-configured, and very well cut.

You then moved to England and connected with the Bristol scene. The festival needed new patronage.

KR Yes, luckily they all appeared in that Brisbane wave. There was a big influx in the late 70s: musicians, artists and social workers. They were really quite smart, sophisticated and articulate, coming out of such a repressive regime as Bjelke Peterson’s. I think it was a natural progression that this new group would take over the next festival.

Posters, Sydney Super 8 Film Group

Courtesy D/Lux/Media/Arts

Posters, Sydney Super 8 Film Group

MT My earliest involvement with Super 8 in Sydney was contributing two films to the second festival in 1981. After that festival Ross Gibson, Lindy Lee, Deirdre Beck, Janet Burchill and myself got together and we called ourselves the Super 8 Collective.

After successfully applying for a grant from the Australian Film Commission we held the 3rd Sydney Super 8 Film Festival in November 1982 at the Chauvel Cinema in Paddington. The cinema had a capacity of 300 hundred seats. It was full every night and was like that for every annual festival for most of the 80s. I don’t think there were many sophisticated debates around the selection process. We were a test audience, a colosseum forum that voted thumbs up or down.

There was a scene there that grew in sophistication as long as the technology was viable. Over that period a new core of people began to develop with Gary Warner, Virginia Hilyard, Michael Hutak, Catherine Lowing, Andrew Frost and myself. We also did a whole series of Film Readers as well as the festival catalogues and posters, all of which demonstrated a post-do-it-yourself-new-wave aesthetic.

What were some of the political and aesthetic considerations of the filmmakers involved?

MT Andrew Frost, Michael Hutak, Gary Warner, Stephen Harrop and myself all eventually formed Metaphysical TV. We all made films about our relationship with the television screen. We used Super 8 to shoot directly off the screen, reconstructing the material into some personal or perverse work. It all fell into current discussions of post-modern quotation and appropriation. Catherine Lowing was working with a similar sensibility but without the direct relation to television; she was into subcultures, rockabilly, video clip…and dance cultures. Virginia Hilyard was more into a poetics of cinema; she did experiments with expanded live performances. Her work was close to neo-expressionist painting of the time, very visceral and physical.

What did post modernity mean for Sydney Super 8 film scene?

MT I remember the event that crystallised the understanding of postmodernism in relationship to visual art practice was the Futur*Fall conference at Sydney University in 1984. Baudrillard was the keynote speaker. Lots of people identified postmodern concerns in literature, film theory, fine arts, architecture and economics.

For most of the Super 8 filmmakers what appeared as postmodern in their work had come about quite spontaneously. Instead of taking up the previous generation’s tendency to critique entertainment culture and reject it out of hand we savoured it for aesthetic and expressive effect, touched it up in a certain way, rebuilt it to make it even more perfect. To even make it articulate where it had been dumb, and thoughtful where it had been ignorant.

Posters, Sydney Super 8 Film Group

Courtesy D/Lux/Media/Arts

Posters, Sydney Super 8 Film Group

KR I think collage and those sorts of ideas were the precursors of postmodernity as a technique and had been around for decades. The beauty with reversal stock was we could cut it and stick it; the medium lends itself to being treated that way. We questioned and broke things down. The thin edge of postmodernist reach, though, is just pastiche.

In the 80s you were seen as a vigorous proponent of Super 8 especially in regard to the concept of the ‘Super 8 phenomenon’ and ‘Super 8 effect.’

MT From very early on there was a feeling that Super 8 was special, that there was more to it than just a cheap mass-produced medium. To me it was more than film, it was a way of life, involving an act of sub-cultural revelation. It was really a kind of formalist analysis of the medium. I argued that Super 8 was invisible to practitioners of other gauges, that a certain repressed consciousness was able to return to the surface through the radical incompetence of untrained but otherwise creative Super 8 filmmakers. There were heated debates and differences of opinion about that. As a critical response Edward Colless put it really well, that ‘Super 8’ really defined nothing, that to call an evening of films simply ‘Super 8’ was as crazy as calling an exhibition of paintings ‘Oil Paint.’ I like to have it both ways, and say yes there is a Super 8 effect, it is liberating and empowered by radical incompetence. But also in Sydney and the city scene something happened that is still to be fully articulated; because of the particular place in time, fuelled by art schools and fringe dwelling film specialists and the nature of Super 8 cameras and instant technology.

KR I think the Super 8 scene was metonymic of people’s need to have time-based media. I think equipment was there waiting to be grabbed. It represented the first of what is a long line of domestic media. There is a political imperative about getting the means of production into the hands of non-experts. I think it’s a little bit facile to say it is the medium.

What relevance does Super 8 have today?

MT I know that there are still Super 8 film festivals in Melbourne and Super 8 is still being picked up by new generations of filmmakers, usually as a device for symbolically representing the past. So you have to say Super 8 never really went away, it just changed its context and its symbolic presence. The result is that the Super 8 phenomenon of the 1980s is really well documented and sits there as a resource waiting to be activated at any time.

d/Lux/Media/Arts are doing that right now with the launch of their web archive that is a repository of every work shown since the 1980s through the 90s and up to recent d>Art events. The archive includes digital versions of films, lists of all the screenings and works, all the writings and artists details from the last 25 years. Amnesia need no longer be an affliction for the experimental screen community!

SynCity, curator Mark Titmarsh, Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, Oct 19-Nov 26, 2006; dlux.org.au/syncity

d/Archive can be visited at http://archive.dlux.org.au

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 pg. 23

© Bob Percival; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Passio

ONE OF THE DISTINCTIVE FEATURES OF THE PROGRAM FOR THE 2007 ADELAIDE FILM FESTIVAL (AFF) IS ITS EMPHASIS ON SILENT FILM WITH THREE STRONG ATTRACTIONS: PAOLO CHERCHI USAI’S PASSIO, ROLF DE HEER’S DR PLONK AND A SCREENING OF D.W. GRIFFITH’S INTOLERANCE WITH LIVE ACCOMPANIMENT BY LOCAL BAND, THE DEADBEATS. GIVEN THE GRAND CLAIMS FOR NEW MEDIA IN THE DIGITAL LANDSCAPE, IT SEEMS SIGNIFICANT THAT OLD MEDIA ARE SIMULTANEOUSLY RETURNING TO PROMINENCE.

One common thread linking AFF events is the relationship with live music which has sustained the renaissance of interest in silent film. Film theorists, for many decades, have noted that the diffusion of synchronised sound in the later 1920s and the rise of a dialogue driven cinema added to the realism of the image. These three projects, while with very different geneses, employing divergent aesthetic strategies and addressing different publics, all circle around the idea of returning the image to a space where it can interact as an equal with the more abstract structures of music.

Paolo Cherchi Usai is the Director of Australia’s National Film and Sound Archive, as well as one of the world’s most respected film archivists and historians. Passio, his feature compilation of found footage and calligraphy, accompanies Arvo Pärt’s musical adaptation of the Passion from The Gospel of St John. Pärt’s music will be performed by the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra with organist Christopher Bowers Broadbent and the Theatre of Voices directed by Paul Hillier.

Cherchi Usai has spoken of his interest in producing a dialogue between image and sound. To the extent that the film has a subject, he sees it as dealing with our society’s history of image production. He sees the sum total of our images as a kind of repressed collective memory, and in interviews he has invoked writers such as Mircea Eliade who emphasise the symbolic role of imagery.

He is also interested in the image as image in a very concrete sense. In an attempt to restore what Walter Benjamin called the aura of the individual artwork, lost in the age of mechanical (and now digital) reproduction, only seven prints of the film were struck before the negative was destroyed. Each print is hand-coloured in a different hue, with four cool prints (ruby, violet, indigo and magenta) and three warm prints (vermilion, gold and minimum colouring). No one print of the film is like another, just as no one performance of the work will be like another.

Dr Plonk

From the sublime to the ridiculous. In an industry where the hardest thing is to make your second film, Rolf de Heer was travelling with his tenth feature, the AFI-winning Ten Canoes, while cutting his eleventh, Dr Plonk, which is the AFF’s closing night film. By Australian standards, de Heer comes up with some pretty daring ideas. Having made a subtitled film in an indigenous language with a group of non-actors, he has backed up with a silent, slapstick comedy. To de Heer, these aspects of his career are related. “The more radical I get, the easier these things are to finance,” he said at a Media Resource Centre talk in Adelaide recently.

His last two films are linked in more pragmatic ways as well. The overrun in making Ten Canoes meant that de Heer needed to make another film relatively quickly. He tells of going to the fridge to get some insect repellent in preparation for a trip north and finding instead 20,000 feet of film stock past its expiry date. At that moment, he knew he had his next project: a film which would invoke the look of silent cinema, where any deterioration in the stock would be immaterial as it would be printed in black and white, and in a genre where we expect films to be far from pristine in condition.

Though the inspiration for Plonk stemmed from these humble beginnings, this was to be no simple project. De Heer says that many of his films “begin first as a contrivance and only after that become a great passion.” He decided that his silent film would have to be shot in the style of silent films—the slapstick comedies which he had seen on television in his childhood—but also employing as much of the technology as was feasible. He and cinematographer Judd Overton set about finding a hand-cranked camera to give the image a pulse in the inevitable variations in winding speed.

On first glance the project suggests comparison to Borges’ story about Pierre Menard who re-writes Don Quixote word for word in the present day—and in the process creates a completely different work. De Heer insists that the film “has to be its own thing. You can’t replicate silent film,” he explains, “but it’s in the tradition of silent film.” Some early attempts at technological authenticity were abandoned. The 1920s camera bought on eBay was jettisoned for a Mitchell modified for hand-cranking; black and white processing and cutting on film were replaced by digitising the negative for editing and then outputting back to film. An early plan to record a soundtrack on a theatre Wurlitzer was also abandoned in favour of an accompaniment by a Melbourne group, the Stiletto Sisters, which will be performed live at the Adelaide premiere (de Heer’s The Tracker was presented at the 2002 Melbourne Film Festival with Archie Roach performing live). The experimentation with sound that has characterised de Heer’s filmmaking has often taken the form of separating picture and sound as elements in their own right. The multiple strands of sound in Ten Canoes with David Gulpilil’s voiceover existing in a separate space to the narrative diegeses is another case in point.

Perhaps the most interesting concession de Heer had to make to an earlier style of filmmaking was the substitution of editing with complex staging. Rather than shooting standard coverage for an editor, the camera is held back in full shot, and like great filmmakers such as Feuillade, Bauer or Keaton, de Heer has to re-discover the craft of the early silent period—learning how to direct and quickly re-direct the audience’s attention to the salient dramatic business.

In a film so outlandishly different from Ten Canoes, de Heer has paradoxically come back to the same ground in Dr Plonk, with the need to find the formal means in picture, sound and drama to imagine a radically different time and place. Here is another attempt to regain the past, just as the protagonist of Ten Canoes has to recover the past of his ancestral cosmology before he can die, just as de Heer the image-maker tries to recover the past of anthropologist Donald Thomson’s photographs.

De Heer’s experiment in re-discovering cinema through anachronism is not an isolated one. In Wisconsin for instance, the university’s filmmaking department runs a course in silent filmmaking which tries to replicate as closely as possible the film stock, camera equipment, lighting conditions and processing technology available to filmmakers at the birth of the medium (mywebspace.wisc.edu/dhfuller/web). For film historians, the benefits are a closer understanding of the conditions and constraints faced by the filmmakers, while for those interested in becoming filmmakers, silent film offers a tangible encounter with the material basis of the medium in ways which have been lost by the “point and shoot, click and drag” methods of digital video.

The third silent program at AFF has its origin in the Media Resource Centre’s Silent Re-masters series, which has given rise to The Deadbeats’ accompaniment to DW Griffith’s 1916 classic Intolerance. Re-scores of silent films by rock groups or electronic musicians commonly polarise opinion. Some view it as a refusal to see history in any terms other than contemporary ones. For others, it acknowledges that these films were intensely modern and popular in their historical moment, and that as electronic and rock music occupy an analogous cultural space today, they can help translate the films into contemporary idiom.

Rather than play over the film, The Deadbeats (bass, drums, guitar, keyboard and spoken word picking out key intertitles) provide a spare accompaniment which accentuates the rising patterns of action within scenes. Intolerance, with its four interwoven narratives, stands up well to this treatment which refreshes the audience’s respect for the essentially abstract nature of Griffith’s achievement instead of facilely deriding it for its lack of realism.

Adelaide is not alone in foregrounding silent cinema within a festival context. The recent Berlin Film Festival programmed restorations of Giovanni Pastrone’s 1913 Italian epic Cabiria and Asta Nielson’s 1920 version of Hamlet. This rediscovery of silent film is undoubtedly a by-product of Pordenone’s Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, an annual festival begun 25 years ago by a group including Cherchi Usai, and which has included strands on 21st century silents, including filmmakers such as Guy Maddin. The lesson here might be that, as much as artists envision the future, there is something both perverse and prudent about turning in the other direction and absorbing the lessons that history has to offer on the production and consumption of screen images.

Adelaide Film Festival, Feb 22-March 4

www.adelaidefilmfestival.org

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 pg. 18

© Mike Walsh; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

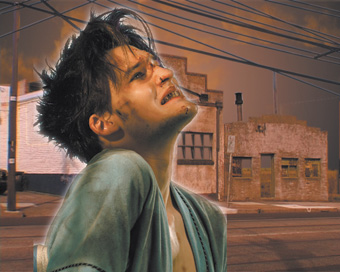

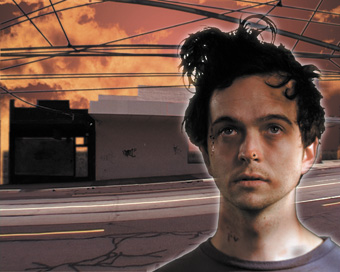

Richard Green, Boxing Day

KRIV STENDERS’ BOXING DAY IS A DOMESTIC DRAMA FOCUSING ON A MAN ON HOME DETENTION WHO UNCOVERS A DISTURBING TRUTH WHILE ATTEMPTING TO RECONCILE HIS ESTRANGED FAMILY. SOLELY FUNDED BY THE ADELAIDE FILM FESTIVAL AND UNFOLDING IN REAL TIME IN ESSENTIALLY ONE CONTINUOUS TAKE, THE FILM IS A FOLLOW UP, NOT JUST CHRONOLOGICALLY BUT METHODOLOGICALLY, TO STENDERS’ MICRO-BUDGET BLACKTOWN, WHICH WAS A HIT AT THE 2006 SYDNEY FILM FESTIVAL (WHERE IT TOOK OUT THE AUDIENCE AWARD), MELBOURNE, BRISBANE, PERTH AND CANBERRA FILM FESTIVALS.

Blacktown is shortly to be released on DVD by Madman Entertainment. Ahead of Boxing Day’s world premiere at AFF, I spoke to Kriv Stenders about his working methods, casting strategies and stylistic formalism.

“The seed for the film happened ten years ago when I made a short film called Two/Out,” says Stenders of his first collaboration with Boxing Day co-writer and star, indigenous poet, musician and sometime actor, Richard Green. “I met both Tony Ryan [star of Blacktown, RT67, p22] and Richard through making Two/Out. Richard and I stayed in loose contact, and when I made Blacktown with Tony I touched base with Richard. Then, because of the experience I had with Blacktown, I thought it would be great to make a film with Richard in a lead role. Basically having that experience under my belt I decided to do Boxing Day.”

The film’s scenario involves Green’s character, Chris Sykes, a recovering alcoholic and criminal, preparing Christmas lunch when an old friend turns up uninvited at his doorstep and reveals a secret regarding his family. When Chris’ daughter, his wife and her new boyfriend finally arrive, the situation inevitability escalates in tension towards revelation and conflict. Dark and relentless when compared to some of the relatively lighter and romantic moments of Blacktown, the film’s tone was dictated by Green’s presence: “ Tony [in Blacktown], who’s very gregarious, with a lot of light inside him, he was ideal for that type of film, while Richard is a lot more conflicted. I knew that he’d be able to play intensity really convincingly, absolutely perfect for some kind of heavily dramatic role. And it just kind of fed from there. Well, we thought, what about a siege situation? He’d be really good in that. How about that? What about a domestic situation, the ones you read about in the papers at Christmas when families go off the rails? Perfect. That’s where it started. Richard can do this sort of character. What kind of story would that character inhabit? Work with that, and the story kind of wrote itself from that point. And it became this kind of confronting, quite unrelenting piece. Hopefully with some kind of light in it as well.”

The writing process for Boxing Day never advanced to a full draft screenplay, but what Stenders calls a “scriptment”, which had precisely laid out story beats and sample dialogue, but with enormous scope for flexibility and improvisation. A limited cast of six and one location was suited to this form of organic evolution of narrative and character. “Basically we had a three week period to produce the film. So for the first two weeks we rehearsed the film chronologically, and shot it. At the end of the first week we had a version of the film, which we could sit back and watch. Every night I’d pick the best bits and cut it together. So at any point of the day we had the film, and we just added on the next dramatic layer. By the second week we had a second version of the film and we really knew what the weak points were, what the twists and turns were, and were really able to refine the story and address a lot of dramatic issues and character issues.” This was a more structured approach than the guerrilla approach to the making of Blacktown. “Blacktown was shot over about eight months. And it wasn’t as concentrated or disciplined as this. Boxing Day is a much more contained enterprise. It was more finite. But because we had finite resources and finite time, I think it worked really well, because it really helped focus everything.”

Stenders is a passionate advocate of backing the abilities of non-actors, as long as they bring an intrinsic talent and legitimacy to the role, and he encourages them in certain scenarios to construct their own dialogue and action. “Because you’re not bound by script or hitting lines, it can help alleviate stilted performances, and it’s important to get actors who are more like jazz musicians, who are able to improvise, riff off a melody, and come back to the basic rhythm again.” A non-actor, Stuart Clark, plays Chris’s drug-dealing colleague in Boxing Day, his services attained through contact with the Offenders Aid and Rehabilitation Services of SA. A similar process was used to cast Stenders’ short film Two/Out, “and it’s a risky thing to do because some of these guys are struggling with internal issues. But Stuart brought something inherent, he brought some authenticity and a lot of credibility to Boxing Day.” The end result of Clark’s natural performance is compelling, full of implied menace and idiosyncratic phrasing.

While most of the cast were taking their first roles, they were also offset by the presence of two professional actors in Syd Brisbane and Tammy Anderson. This blending of experience and rawness was very deliberate: “In a funny kind of way they feed off each other. Non-actors can be more tangential and unpredictable but the actors can always bring them into line, and vice versa…it’s all about casting. From my point of view directing is 99% casting.”

Trained as a cinematographer, Stenders himself shot Boxing Day with a hand held, intimately observational approach of one extended take in a digital format. Aware that this brand of cinematic experiment has been attempted before, he acknowledges predecessors like Russian Ark (Aleksandr Sukorov, 2002) and Time Code (Mike Figgis, 2000): “So it’s not that groundbreaking, but I think what’s different about Boxing Day is that we’re telling a linear story. It’s all about the story, really.” His ambition for Boxing Day is to balance an aesthetic style, a narrative structure, and the technology of the medium, into something cohesive:

I really love digital as a medium and I really like to find new ways of telling stories to make films. In a funny kind of way, I think digital has been the best thing to happen to cinema in the last twenty years, because the freedom it gives you to work outside of normal systems, styles, formats or traditions is great. So I wanted to do something where the form and content were the one thing and kind of inform each other. And I just really like the idea of doing long takes, and never cutting and always being in the moment.

Having made Illustrated Family Doctor, a traditional feature on 35mm—although that was a lot of fun—the thing I learn as I make more and more films is that if I frighten myself, if I put myself in compromising positions I find that the payoff is more rewarding than by being safe.

Adelaide Film Festival, Feb 22-March 4, www.adelaidefilmfestival.org

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 pg. 17

© Sandy Cameron; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Alma (Victoria Hill) & Rupert (Ben Mendelsohn) at Vogue

photo Rose Draper

Alma (Victoria Hill) & Rupert (Ben Mendelsohn) at Vogue

LIKE AN AUSTRALIAN VERSION OF TIM BURTON’S ED WOOD (1995), HUNT ANGELS (ALEC MORGAN, 2006) IS A BIOPIC ABOUT A NOT VERY SUCCESSFUL, BUT VERY PASSIONATE, PAIR OF FILMMAKERS STRUGGLING OUTSIDE THE HOLLYWOOD RUN SYSTEM IN THE EARLY YEARS OF CINEMA. STARRING BEN MENDELSOHN AS THE FAST-TALKING RUPERT KATHNER AND VICTORIA HILL AS ALMA BROOKS, HIS ALLURING YOUNG CAMERAWOMAN, THIS SAD TALE OF THE DUO’S PERSISTENT BUT DOOMED STRUGGLE TO TELL AUTHENTIC AUSTRALIAN STORIES IS PORTRAYED IN SUMPTUOUS BLACK AND WHITE ART DECO STYLE.

Seamless computer manipulation embeds the two actors into stills and newsreel footage from the 1930s and 40s and intercuts them with interviews of still living contemporaries. Hyper-stylised mise-en-scène is reminiscent of film noir. Costuming and makeup is authentic to the period and immaculate. Even the transitional wipes from re-enacted footage to present-day interviews have the feel of the 30s. The use of matting and green-screen recording of the two actors playing the forgotten filmmakers integrated into hundreds of archival images has resulted in a documentary film consisting of 281 special effects shots, which “deploy…contemporary electronic means to fuse together the story of two filmmakers ‘lost’ from our written history with ‘lost’ images of Sydney of the era in which they lived” (Alec Morgan, “Re-telling history in the digital age: The scripting of Hunt Angels”, Scan: Journal of Media, Arts, Culture).

With more chutzpah than talent, Kathner and Brooks made nineteen films before ‘Rupe’ died of a brain hemorrhage in 1954 at the age of 50. Unfortunately, none of these bear scrutiny today, especially when stacked against the better funded works of their contemporary cinemateurs such as Charles Chauvel, whose Rats of Tobruk (1944) scuttled Kathner and Brook’s own plans of a desert war saga. Despite being pioneers in Australian cinema, their contributions don’t even rate a mention in the Australian Film Institute’s A Century of Australian Cinema (1995). The short-lived screenings of their films took place only in the so-called ‘flea-pits’ of Sydney, because, as David Stratton points out, “the two main cinema chains were majority owned by foreign companies (Hoyts by 20th Century Fox and Greater Union by Rank Organization)“, (“A true Aussie gem”, The Weekend Australian, December 2-3, 2006), and these cinemas could only play films sanctioned by the Hollywood owners.

Distribution was monopolized by Hollywood companies, too. Rarely were Australian-made features screened and Kathner and Brooks were under constant financial strain, with many of their filmmaking ventures being little more than scams to milk money from gullible investors, or ‘angels’. Morgan explains their appeal: “They were partners in moviemaking, love, and (as it turned out) crime” (“Lost city of the senses”, Scan: Journal of Media, Arts, Culture). For their Pyjama Girl Murder Case (1939), Australia’s first ‘true crime’ movie, Alma stripped and lay in a bathtub, pretending to be a corpse that had been steeped in formalin for five years, because access to the real thing was denied by the NSW Police Commissioner, “Big Bill” Mackay. The pair’s earlier break-in to the Sydney University Medical Faculty to film the body failed due to lack of a replacement bulb when their only lighting rig blew. Finally, to get permission to continue with the film, Kathner manufactured death threats against himself and ‘leaked’ them to the media: “Big Bill” relented and the film was completed.

Hunt Angels

photo Rose Draper

Hunt Angels

After a state ban on bushrangers in film was overturned in 1946, the pair’s Ned Kelly film, The Glenrowan Affair (1951) employed numerous different leads according to whomever they could con. The movie’s ‘stars’ came from grazing properties around Victoria’s ‘Kelly country’ and contributed financially in return for the leading role. As a result Kathner and Brook’s ‘Ned’ was variously short, tall, fat and thin. Although the feature films with which they unsuccessfully took on the Hollywood stranglehold have all but sunk without a trace, with none ever turning a profit, Kathner and Brooks did contribute significantly to the newsreel genre, by depicting the actual misery and squalor of the Depression era in their Australia Today pieces of 1938-40, which were in stark contrast to the artificially optimistic Fox-Movietone News and Cinesound Review newsreels. Morgan laments the habit of historical surveys of Australian film to overlook the newsreel at the expense of features:

Because of the exclusion policies of Fox and Cinesound, moving images of the poorer, noir world of Sydney that Kathner and Brooks inhabited and filmed are missing from our popular memory. Generations have grown up seeing a Depression-era Sydney depicted as a sunny, prosperous place with beaches full of happy bathers and bronzed lifesavers. Even today, because of their easy access, the Fox-Movietone and Cinesound News collections are the most extensively used sources of factual footage of that era. (“Re-designing the past imperfect: The making of Hunt Angels”, Senses of Cinema, 2006).

By depicting Depression-era Australia as it really was, Kathner and Brooks should have earned a place in Australia’s cinematic history, but their fringe existence has meant they have been under-screened and overlooked…until now, that is.

Biopics of filmmakers have not been common in Hollywood: apart from Burton’s Ed Wood, Bill Condon’s Gods and Monsters (1998) about horror film director James Whale also springs to mind. Morgan’s work is the first biopic of an Australian filmmaker: biopics here have included a sports star, Dawn Fraser in Dawn! (Ken Hannam, 1979); criminals, Mark ‘Chopper’ Reid (Chopper, Andrew Dominik, 2000) and Brendan Abbott (The Postcard Bandit, Tony Tilse, 2003); a writer, Miles Franklin (My Brilliant Career, Gillian Armstrong, 1979); a pianist (David Helfgott in Shine, 1996); and Ned Kelly in a plethora of films. One commonality in Australian biopics is the recurring theme of a unique individual’s struggle against the establishment. But the underdog need not win: Albert Moran and Errol Vieth note in Film in Australia in their chapter on the Australian biopic: “there is no obligation on the genre to trace an ever-upward path on the part of its central figure. Triumph and affirmation may only be incidental moments in the biographical film” (Film in Australia, Melbourne: Cambridge UP, 2006). Kathner and Brooks were certainly underdogs.

Nevertheless, Hunt Angels serves as an instructional piece for contemporary Australian filmmakers, who have it comparatively easy. Since the 1970s Australian filmmaking has been greatly assisted by the state film development organisations in what has been called The Revival. Before this financial revitalisation, cinema in Australia was a mostly US lead affair: 95% of films screened were US productions distributed by US firms and shown only in cinemas they approved. This was the hostile environment in which Kathner and Brooks operated. Paul Kathner says in the film: “My father wanted to tell Australian stories—he was fed up with the Americanization of films.”

It is this passion to break away from Hollywood controlled production, distribution and screening and to tell Australian stories that drove Kathner and Brooks. It is this same intention to do things in an anti-Hollywood way that seems to have driven Morgan to choose two movie-making failures to be the subject of a film. Moran and Vieth write of the Australian biopic, “What matters is not the historical importance of the life but rather that the life actually happened. Beyond that, generic form and style intervene to ensure that the biographical subject becomes a screen subject.” Morgan creatively uses Art Deco style and form to turn a forgotten biographical subject into a captivating screen subject, something that would never have seen the light of day were it a story about two unknown filmmakers in Hollywood. Instead of choosing a successful Australian cinematic legend like Charles Chauvel, the subject of numerous historiographies, Morgan has disclosed the quondam reality of our lesser-known Australian movie-making background. As David Stratton has said of Hunt Angels, “if you care anything about local cinema, the result is essential viewing.” Hunt Angels has filled in a small blank in our cinematic and cultural history, re-coloured an effective whitewash of the Depression-era wretchedness of Sydney by Hollywood sanctioned sanitised newsreels, restored a nation’s previously censored memory, and done so with an unmistakable anti-Hollywood sneer.

Hunt Angels won the 2006 Film Critics Circle Australia Award for Best Feature Documentary and the Atom Award for Best General Documentary.

Hunt Angels, writer-director Alec Morgan, cinematography Jackie Farkas, lead compositor and visual Fx supervisor Rose Draper, visual effects consultant and post-production supervisor Mike Seymour, production designer Tony Campbell, costumes Margot Wilson, editor Tony Stevens, composer Jen Anderson, producer Sue Maslin; Palace Films with Film Art Doco and Blusteal Films, 2006 www.huntangels.com.au

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 pg. 24

© bruno starrs; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

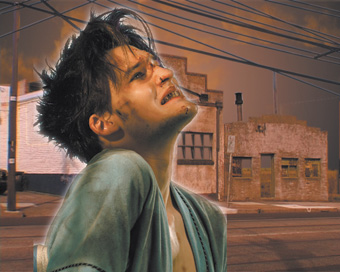

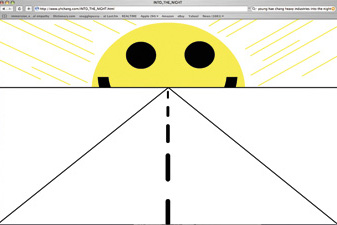

(Out of the Internet and) Into the Night, Young Hae Change Heavy Indsutries

IN A LARGE STUDIO ADJOINING THE NEW STATE LIBRARY OF QUEENSLAND, MAAP 2006 OFFERS VISITORS INTIMATE, INTENSIVE BROWSING OF MEDIA ART IT HAS COMMISSIONED AND COLLECTED. THE LIBRARY, A PARTNER IN MAAP'S OUT OF THE INTERNET, IS IMPRESSIVE ARCHITECTURALLY, IN SCALE AND IN THE ARRAY OF SCREEN AND COMPUTER FACILITIES AVAILABLE TO USERS. IT'S WELL PLACED AS PART OF THE SOUTHBANK CULTURAL PRECINCT BETWEEN THE QUEENSLAND ART GALLERY AND THE SPECTACULAR NEW GALLERY OF MODERN ART. MAAP FITS WELL IN THIS SCHEME OF THINGS, EMBRACING AND INTERROGATING NEW MEDIA WORK AS ART AND SIMULTANEOUSLY AS PART OF GLOBAL COMMUNICATION NETWORKS.

In titling MAAP 2006 Out of the Internet, artistic director Kim Machan was hoping to give internet art a palpable exhibition presence as well as an online life: “I am shepherding the work back into taking a material form in the museum context, to achieve authority, blending the different fields in which they operate, and joining another official art history context. Making a representation of all the works in the State Library of Queensland adds another dimension—or escape route—out of the closed museum context” (RT 75, p2).

This physicality manifests itself for visitors too. Near the entrance to the exhibition, on Singapore based artists Charles Lim and defence scientist Melvin Phua’s exercise rowing machine, alpha 4 (GENERATOR), you work hard until the point at which you’ve powered up the battery which kickstarts a computer that is set up as a server for its own website and which sends the image of you rowing out around the world. As Machan observes in her catalogue notes, there’s something dryly funny about an “overly earnest scientific approach coupled with the absurdly circular demonstration.” This is interactivity that not only makes you work but triggers ideas of bizarre potential applications.

(Out of the Internet and) Into the Night, Young Hae Change Heavy Indsutries

In the relaxed MAAP exhibition space, scaffolding creates a second level to which you climb to view YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES’ flash animation, Into the Night, on a big screen, or look left to another featuring G’day, G’day by Japan’s Candy Factory. Beneath the floor are rows of video monitors on which, with headphones, you can choose to view a host of DVD-based works from the Move on Asia Clash & Network Exhibition originally shown in Seoul and Tokyo and, once sifted through, featuring some strong work. A seat per screen makes the experience a serious as well as comfortable one (galleries take note). In Zhong Shuo (People say…; Australian artist Iain Mott with Chinese collaborators li Chuan Group, Ding Jie) you can set yourself down on cushions in a small house to hear Chinese people speak of their experience of cities as they change (www.reverberant.com; RT 71, p26).

As promised by Machan, YOUNG-HAE CHANG INDUSTRIES’ Into the Night offers a cinematic version of what is usually an internet experience. The Korean pair have created a wickedly witty text rendition of a film-noirish road movie replete with the artists’ own fine jazz score backing a hilarious argument in aptly dead-pan computer-generated speech. The only concessions to imagery (the scale, distribution and lyrical movement of the words make the art here) come in the form of road markings flickering into the distance and a happy face sun on the horizon. There’s a shocking crash (the word falls off the screen) and fitting closure after droll renditions of Talk About It and Funky Town: “You kill me.” Go to www.yhchang.com to see Into the Night, and many more inventive works, on the small screen, but it must be said: BIG is good.

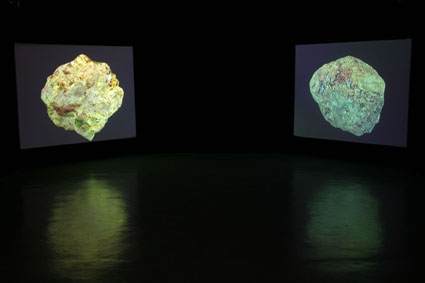

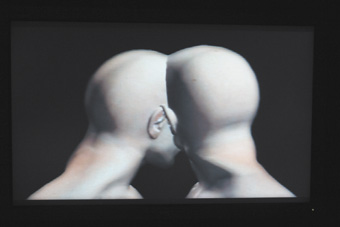

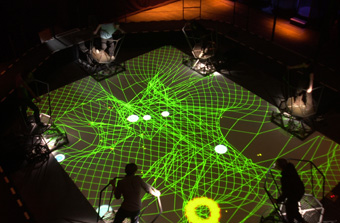

Feng Mengbo, The Invisible Words: A GPS Calligraphy Project, 2006,

Feng Mengbo, The Invisible Words: A GPS Calligraphy Project, 2006,

Moreton Bay, November 2006

As with Candy Factory and Young Hae Chang, Feng Mengbo (China) has a longstanding relationship with MAAP. GPS technology is employed quite laterally in his appealing Invisible Words installation. He uses it to ‘write’ Chinese characters across city maps (www.maap.fengmengbo – expired) and oceanographic charts. The artist travels the route (in “kilometres’ long brush strokes”) determined for him by the shape of a an ideogram and records the result as he goes. For MAAP he worked off the coast of Queensland. The finished exhibits, where the techno-calligraphy hovers beautifully between the impressionistic and precise, are accompanied by images of the artist ‘writing’ at sea. RT

MAAP: Out of the internet, artistic director Kim Machan, State Library of Queensland and international partner venues, Nov 30, 2006-Jan 25, 2007; www.maap.org.au. For the full extent of MAAP Out of the Internet activities see Danni Zuvela’s interview with the curators in RealTime 75.

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 pg. 34

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

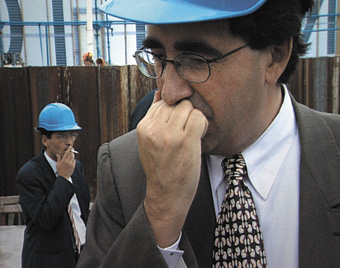

Yuri Chursin, Playing the Victim

RUSSIANS SEE THINGS A LITTLE DIFFERENTLY FROM WESTERNERS. TO THEM, LIFE IS BLEAKER, STUPIDER, DEEPER, FUNNIER AND ALWAYS MORE ‘HUMAN.’ THEIR FILMS REFLECT THIS PERSPECTIVE. THERE IS ALWAYS AN AUDACITY IN RUSSIAN CINEMA. EVERYTHING SEEMS TO BE HANGING, TENUOUSLY ABOVE AN OCEAN OF CHAOS. IN AUSTRALIA, WHERE LIFE IS TOO SAFE AND EASY, IT’S LIBERATING TO OBSERVE SUCH ARTISTIC RECKLESSNESS. RUSSIAN FILMS CAN SHAKE OUR BENEVOLENT PLATITUDES, REAWAKENING OUR SENSE OF COLD, INVIGORATING REALITY. FORTUNATELY, THE 2007 ADELAIDE FILM FESTIVAL WILL BE SHOWCASING SIX DIVERSE EXAMPLES OF NEW RUSSIAN FILMMAKING TO REMIND US OF THE POWER OF THIS INIMITABLE NATIONAL CINEMA.

At the top of the list in this year’s season is Alexander Sokurov’s The Sun (2004). For the uninitiated, Sokurov is the most accomplished filmmaker working in Russia today, largely known in Australia for his single-shot historical panorama Russian Ark (2002). The Sun presents the third instalment in his Men of Power series. Following depictions of Hitler in Moloch (1999) and Lenin in Taurus (2001), The Sun focuses on the life of Japanese Emperor Hirohito in the days leading up to his capitulation to the US led invasion in 1945. A biography of sorts, it follows Hirohito (Issei Ogata) through the twisted layers of his character, through its defects and peculiarities, towards the moment when he will renounce his sanctified divinity as a sun god for the sake of international peace and personal happiness.

A controversial work, Sokurov’s film has generated considerable hostility in many countries, particularly in China where its sympathetic depiction of Hirohito has been received as an insult to the victims of Japanese atrocities. Indeed, as historical record, The Sun is at best problematic. But history is not the film’s real interest. What Sokurov captures is not the life of a man as normally understood, but rather the bare emotional imprint of a life, of a human animal clothed in an illusion of ritualised power and sickness. The style reflects this concern. Green-brown sepia images and warped, fluctuating proportions conjure disease or hallucination. Hirohito himself notes an ever-present “bad smell and bad taste”, sensations exacerbated by the score’s remarkable arrangement of music and noise into a low intestinal drone. Like the best of 19th century Russian literature, Sokurov reveals the aura or tone of each scene, isolating the human experiences within it. Perhaps the film’s greatest asset is the actor Ogata. His performance as Hirohito is quite unlike any I have ever witnessed, not so much that of a psychology as of a soul: anguished, silent and invisible. These qualities give The Sun an artistic value rarely matched in contemporary filmmaking.

Pavel Lunguin’s The Island (2006) belongs to the same school of Russian filmmaking (one traceable to the influence of celebrated director Andrei Tarkovsky). A less complex film than The Sun, The Island is a character centred study of sin and redemption. Having washed up on the shores of a remote monastery, Father Anatoly (Petr Mamonov) spends his life segregated from the rest of the order as an eccentric prankster and mystic. He administers to the sick, plays tricks on other priests and makes a general mockery of Orthodox ritual, all to encapsulate a genuine example of Christian faith: devotion to God and nothing else. But the pain of his past sins will not go away. Impressively shot on a lavish budget, The Island is propelled by a wonderful performance from Mamonov, whose Anatoly humanises the script’s religious concerns with compassion and warmth. It’s a serious film, but accessible.

In a totally different realm is Kirill Serebrennikov’s black and dry comedy, Playing the Victim (2006), recently voted Best Film at the Rome Film Festival. Previously anonymous as a filmmaker, Serebrennikov has experienced considerable success over the past ten years as a theatre director of contemporary and usually scandalous Russian plays. His new film sees him bringing one such work to the screen, Playing the Victim by brothers Vladimir and Oleg Presnyakov. It begins unabashedly: “Russian cinema is in big shit. Only Fedya Bondarchuk is a cool guy. Fedya is cool. His father got an Oscar. And he’ll get one. He’ll get stronger and get one for sure.”

To those in the know the message is clear. This is anti-Tarkovsky, a film concerned only with this life. It is the story of Valya, a near thirty-year-old boy, university graduate and emblem of a new way. Valya works for the police. His job is to stand in for the dead during re-enactments of homicides. It’s cushy work and pays enough for his new toys and clothes. But Valya’s real interest is in revenge: on his mother and uncle who now share his dead father’s bed, and on an entire generation of Russians busy reacquainting themselves with national arrogance. He endorses something else entirely, the cultural ambivalence of anything and everything. Valya practices his gangsta moves, eats blackberries with chopsticks and embraces suicide chic with the best of them. To generations X and Y his stance will be a familiar one. “Ideals don’t exist”, the film’s director has claimed, “and it would be good to have a great deal more common sense…I don’t think we have our own special path or destiny” (The Moscow Times, June 9, 2006). The Russian cultural elite will be rolling in their graves.

Everyone knows that Slavs are the best at being seriously idiotic and First on the Moon (2005) proves it in spades. A mockumentary by Alexei Fedorchencko, it lets us in on a big secret. While many of us are aware that Neil Armstrong’s famous giant leap was filmed in a television studio, few of us have known the whole truth until now. The real, bona fide Moon landing was an unadulterated Stalinist invention. Encased within a prototype interstellar projectile, a small handpicked elite of heroic workers, athletic beauties and limber midgets shot to the Moon on March 16th 1938, returning to Earth one week later as a meteor that landed in a remote alpine region of Chile. The crew survived, its superhuman leader Ivan Kharamalov evading Soviet authorities by assuming multiple identities. He eventually became star of a popular regional circus troupe in a vibrant retelling of Alexander Nevsky. If you don’t believe me go and see First on the Moon yourself. This is a brilliant and hilarious film with fantastic black & white imagery. It won best documentary at the 2005 Venice Film Festival.

At the other end of the truth spectrum is Sergei Loznitsa’s documentary Blockade (2005). Winner of 6 international prizes, Blockade comprises newsreel footage from the 900-day siege of Leningrad (1941-44) during which up to 800,000 Russians died. Choosing to let the footage speak for itself, Loznitsa couples the images only with a minimal soundtrack of effects. For 52 minutes we watch silently on the domestic consequences of war. It is a harrowing and starkly pertinent experience for anyone still unsure about the viability of military invasions.

Finally, Andrei Kravchuk’s The Italian (2005) fulfils an all too often neglected role in festival programs. It’s a children’s film, most suitable for 12-15 year olds. It tells the story of Vanya, a five-year-old living in a dilapidated Russian orphanage. Vanya is lucky. From the dozens of boys surrounding him he has been chosen for adoption by a childless Italian couple. In only a month it’ll be beaches and gelato. But Vanya doesn’t feel lucky. He wants what is his. With a gritty resolve and a knack for language he escapes the orphanage and embarks on a journey to find his real mother. Like the best children’s films, The Italian layers its adventure story with a sophisticated social analysis, presenting a cross-section of Russia’s past and present through the lens of Vanya’s unclouded eyes. It won Best Children’s Film at the 2006 Berlin International Film Festival.

Adelaide Film Festival, Feb 22-March 4,

www.adelaidefilmfestival.org

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 pg. 19

© Tom Redwood; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

IN CHARLES STROSS’ SCI-FI NOVEL THE SINGULARITY SKY, CULTURAL COLONISERS INVADE A PLANET WITH CORNUCOPIA MACHINES WHICH CHURN OUT EVERY KIND OF OBJECT AND TECHNOLOGICAL DEVICE ON THE INHABITANTS’ WISH LIST IN RETURN FOR THEIR IDEAS, HISTORIES AND BELIEFS. THE ALIENS, WHO ARE NEVER SEEN, LEAVE THE PLANET AND ITS CULTURE IN A RIGHT MESS, RUINING THE ALREADY DODGY DISTRIBUTION OF POWER. THE AUSTRALIAN NETWORK FOR ART AND TECHNOLOGY (ANAT) IS A VERY DIFFERENT KIND OF CORNUCOPIA MACHINE, A BENIGN ONE HELPING US MAKE THE MOST, ETHICALLY AND AESTHETICALLY, OF THE NEW TECHNOLOGICAL TOOLS WE ARE FLOODED WITH BY OUR OWN ALIENS, THE TECHNO-CORPORATIONS.

Finger Dress, Joanna Berzowska

courtesy of the artist

Finger Dress, Joanna Berzowska

When I comment on the apparent fecundity of ANAT’s 2007 program, director Melinda Rackham informs me that, of course, Anat is the ancient Egyptian goddess of fertility and crops, and of war. Even so, the program is not quite the horn of plenty Rackham envisaged given limits on funding, consequently “there was some cutting back. So we’re really looking for partners and sponsors outside grant funding in order to employ additional staff to make what we’re doing sustainable.”

in the loop

One of Rackham’s passions is keeping media artists informed, in touch, in the loop. A highly developed mailing list is vital and she’ll look to the model she employed when she instigated the empyre list with its moderated discussions and papers in 2002 (www.subtle.net/empyre). ANAT will also revitalise the lapsed Synapse Database, “an online resource promoting the nexus of art and science”, by bringing writers and curators as well as artists and scientists into its fold (www.synapse.net.au). Because media arts have difficulty connecting with the wider community, says Rackham, it’s vital to attract a diverse audience, “like the scientific community or Cosmos readers [www.cosmosmagazine.com], people who enjoy reading about science. We have to make media arts more visible.” As well, ANAT’s new website, Artport, will play a major role in identifying and promoting artist and organisation members, integrating a diverse field and, as well, reaching out to artists in other fields and a wider audience, “working like a rhizome.”

everyday potentials

A sizeable part of ANAT’s current focus is on the technological innovations pertaining to everyday life. While attending festivals in recent years Rackham noticed developments in techno-wearables. She was alert to how “textile manufacturing and computing shared the same root—think the Jacquard loom and the difference machine. Why not take a different tack and reunite them. It’s aesthetic, it’s fun, technologically advanced and pushing at the edges.” Some wearables are eminently useful, many of them playful and some surreal: Rackham cites the “really practical handbag you can scream into in public places and let the cry out later.” But she also mentions Aphrodite shoes; designed initially for the safety of prostitutes, they are fitted with GPS receiver, alarm and back-to-base signal. (www.theaphroditeproject.tv/saftey). Meanwhile major fashion companies, especially in Italy, are alreading marketing ‘techno-couture’: “Zegna’s parka with pores that open and close, Valetino’s waterproof cashmeres and Alexander McQueen’s papier-mache leather” (“Made in Milan”, Australian Financial Review, Jan 25-28).

The upshot of Rackham’s interest is Reskin, a two-week intensive workshop for Australian media, visual arts and craft practitioners led by prominent overseas makers in the field and related practices: Joanna Berzowska (a Montreal expert in responsive textiles and clothing), Susan Cohn (a Melbourne goldsmith and designer), Stephen Barrass (Canberra-based interaction designer and artist), Elise Co (Los Angeles-based multimedia designer and programmer), Alistair Riddell (Canberra-based interaction design artist and researcher) and Cinammon Lee (Canberra-based metalsmith). Berzowska’s many imaginative and often amusing creations include “memory rich clothing” pictured on this page in the form of a “finger dress”: it’s “an intimacy map of the body, recording and displaying where a person has been touched” (www.berzowska.com).

Rackham is impressed with the high calibre of the Australian artists involved in the workshop (including Keith Armstrong, Somaya Langley, Catherine Truman, Michael Yuen, Robin Petterd) and notes that ANAT, a media arts organisation adopted as a client of the Visual Arts Board in the wake of the recent Australia Council restructure, is leading the way for the board’s traditional clientele in engaging with technological innovation and in an international context. In RealTime 78 Dan Mackinlay will report on the Reskin exhibition and forum.

pixel.play & portable walls

ANAT staff member Sasha Grbich, was one of the EPIC (Emerging Producers in Community) team (RT73, p9), focussing on mobile phone art in regional areas in South Australia with ANAT in the pixel.play program. The next stage of pixel.play is Portable Walls which, says Rackham, “is an outgrowth of the EPIC program and has really grown on its own”. Portable Walls will exhibit on phones and accessible, small DVD player screens the work of young makers and, depending on sponsorship, could tour to over 20 suburban and regional centres around Australia. Rackham says that if she’d seen this kind of art in a gallery when she was growing up in Tamworth: “I would have become an artist much earlier. Exposure of work that we take for granted in the cities is vital in the regions.” Pixel.play will show as part of the 2007 Come Out Youth Festival in Adelaide, May 7-19, featuring work on mobiles from 24 schools in the Mercury Cinema foyer (www.comeout.on.net).

opensourcing