jam tomorrow: art, science & magic

osunwunmi: what next for the body, inbetween time

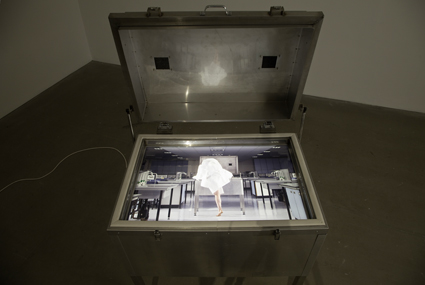

Refolding (Laboratory Architecture), Kira O’Reilly and Jennifer Willet, InBetween Time

photo Jamie Woodley

Refolding (Laboratory Architecture), Kira O’Reilly and Jennifer Willet, InBetween Time

ACCORDING TO THE PROGRAM, ONE OF THE STRANDS OF THE 2010-11 INBETWEEN TIME FESTIVAL, THE EXHIBITION, WHAT NEXT FOR THE BODY, PRESENTS WORKS THAT “CONSIDER THE CONDITIONS AND OUTCOMES OF THE CONTEMPORARY BODY BREAKING DOWN…AT WHAT POINT DOES OUR MATTER CEASE TO BE OURSELVES?”

Director Helen Cole said during an exhibition tour that the commissioned work in InBetween Time came from artists who have a history of working with the body in live art contexts; who have done a whole lot of messing about with insertion and incision and bodily fluids and using the body as their canvas or perhaps their medium; who have on their own flesh tested the limits of endurance, exposure and incarnation. Some of these artists are moving on from thinking of the skin as ultimate border between one reality and another, as a barrier that must be tested and/or crossed. Cole explained that one question guiding her choices in curating the festival was, if you run out of body, then what? And what if the body is over, fails and dies? What about the traces that are left behind? The symposium on February 5 took up this and other issues in more detail.

death, tatts & zombies

In the first session, Dr John Troyer, Death and Dying Practices Associate at the University of Bath, talked about memorial tattoos. In this practice a person’s living body is used as a canvas to display an image of a dead loved one. Troyer’s presentation drew fascinating contrasts between different attitudes to tattooing: 19th century notions that tattooing and criminality are connected; the idea of the Noble Savage; the idea that the body is unfinished and needs to be modified in order to be cultured rather than natural, hence tattoos and body modification; that the tattoo may equally be a pledge of love, a nationalistic affirmation, a gesture of reclamation or a ritualised token; that a tattoo is a visible sign that provokes a narration of its meaning, in order to be activated.

The slides Troyer showed ranged from 19th century post-mortem photographs to a colour snapshot of the tattooed back of a girl he met on the beach. He asserted that memorial tattoos make death visible on a person who wears them. He also mentioned the practice of keeping post-mortem tattoo samples. Some examples from museums consist of a few square inches of inked skin stretched on a frame—what was once a living memorial, a trigger for the exchange of dialogue, memory and imagination in everyday live encounters, becomes an inert graphical object. At this point someone in the audience speculated on whether it would ever be possible to maintain an excised tattoo as living tissue.

Martin Hargreaves’ provocative presentation (he claims his research interests lie between boredom and hysteria) dwelt on what might be the ultimate body; unstable, ugly, predicated on decay and nihilism. Referencing David Wojnarowicz and Bruce LaBruce (RT99, p26), AIDS discourse and “the societal death-wish of the young effeminate,” Hargreaves made an unlikely case for the zombie as a signifier of the attempt to lead an ethical (gay) life. “What are the positives of opening up to zombie logic?” he asked.

Unlike the other contemporary horror tropes of vampire and werewolf, the zombie is not glamorous. Bereft of everything—mind, sense, volition, wholeness—the zombie is helpless to resist invading appetite, and is cannibal; the zombie will inexorably infect others with its own infirmity. It has nothing but its own self, which is defunct. Between helplessness and authenticity, the zombie figures as (heroic) exemplar of our hapless existence.

Mind you, going by Bruce LaBruce’s Otto; or, Up with Dead People, the zombie is rather good looking. So far, so ghoulish.

immortal cancers, divisive dividends

Dr Muireann Quigley talked about legal, scientific and commercial issues pertaining to human remains: cadavers and cell strains. The speaker cited test cases to illustrate the current situation of property in the body. She talked about cell lines and cultures; mentioning such cases as Henrietta Lacks, whose cancerous tumour gave rise to an ‘immortal’ cell line still being used in laboratories around the world, contributing to the profit of the institution that first made a culture of it.

Quigley explained some of the legal precedents that create an economy around bodily remains, producing concepts of ‘bio-equity’ and of a ‘tissue economy.’ “Human bodies and bio-materials are firmly in the realm of property discourse and subject to property relations.” She noted that within this discourse there is conflict between emotional and scientific value, and between public and private realms. Listening to her explain the application of commercial values to bits of people’s bodies had a strangely fetishising effect. This bio-material also has some value simply because, being derived from humans, its use is transgressive, going against contemporary cultural mores. It is as if commercial value becomes a totem which science shakes in the face of those who might question the use of this material. It was odd, to say the least, to catch glimpses of such an archaic mindset underlying the operation of some of our newest technologies.

Refolding (Laboratory Architecture), Kira O’Reilly & Jennifer Willett, InBetween Time,

photo Jamie Woodley

Refolding (Laboratory Architecture), Kira O’Reilly & Jennifer Willett, InBetween Time,

bio-art: science look-alike

Dr Jennifer Willet and Kira O’Reilly, whose collaborative photographic work Refolding (Laboratory Architectures) was part of the gallery exhibition, took it in turns to address the symposium. Willet spoke via Skype from Canada.

She began with a definition of bio-art. The prefixes genetic-, transgenic-, biotech-, vivo-, life-, ecological-, land-, bio- joined to the word ‘art’ all describe practices aligned to or contained within bio-art, whose artistic medium is life or living systems. It is a woolly concept but a large one, and it is easier to define what it is not, than what it is. Bio-art does not represent another thing, it forms neither pictures nor maps. Occurring in the laboratory, it may make use of methodologies more usually seen in studio practice, or may create a scientific methodology peculiar to itself. It is not science, although it may look like science.

Willet asserted that as bio-art involves the manipulation of life to aesthetic ends, it is political, intrinsically involving ethical considerations not conventionally afforded to other art forms. Typically, bio-art must adhere to ethical codes and community standards established by the scientific community. But, according to Willet, in requiring collaboration between artists and scientists, bio-art represents a democratisation of scientific processes.

Kira O’Reilly has been Honorary Research Associate and Artist in Residence at the School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham. In Refolding (Laboratory Architecture), installation photographs portray O’Reilly and Willet in scientific environments. The photographs illustrate a taxonomic system of which the humans are part. Through costume they are coded as part of the system; as observing it; and as camouflaged within it. Willet and O’Reilly wear specially designed white lab coats, each modified to indicate a different era, evoking its associated historical/cultural habits of thought.

The siting and collaborative methodology of Refolding (Laboratory Architectures) within a scientific institution, confers the institution’s credibility on the work. It is fair to say this is characteristic of bio-art.

to infinity and beyond!

The idea of regeneration and what cell technologies might mean for a transhuman, or indeed post-human future became a hot topic of the symposium. The aspiration towards immortality had kept surfacing all day. In spite of the context some element of magical thinking seemed to come in to play, fixing on the potency of physical traces we leave behind. It’s almost as if our detritus, our bits and pieces, achieve a witchy glamour from being at once inanimate while also theoretically capable of being reanimated.

I was comforted to recall something I wrote for the last InBetween Time in 2006: “(Sally Jane) Norman insisted that although technology has extended the human impulse to play with versions of embodiment and variations of reality, this has not changed our fundamental nature. ‘The post-carbon, hairy monkey Stelarc body refutes the idea that we are somehow less physical than we once were.’”

I say comforted. From the Golem to Metropolis to Dr Frankenstein to Planet of the Apes to Alien popular culture views the notion of humans using technology to enhance or engender life with foreboding and caustic cynicism.

jam tomorrow

As demonstrated in Dr Troyer’s presentation, Western culture has historically had a stronger appetite for the ghoulish than is currently generally acceptable. Museums once thought nothing of collecting and displaying anthropological remains, shrunken heads and skeletons of subject peoples, entire skins of tattooed men. These practices are embedded in the history of collecting, and are loaded as drastic acts of objectification of subject peoples’ bodies, a totem activity of the colonial project. However much potency Live Art practice derives from breaking taboos, it would be ironic if seizure of the trophy relic regained legitimacy under its wing.

Jordan McKenzie explained he was a founding member of the Dead Dad’s Club. His performances, a meditation on breath, were a response to watching his father die of emphysema. So, he creates traces: in Drawing Breath, McKenzie breathes into a charcoal covered paper bag which is burst against the wall, leaving a print of its impact. In Condensation Box and Holding My Breath McKenzie breathes into a glass tank, freezing the resultant condensation. The ice dissolves in his hands as he holds it above a block of charcoal, splashing and leaving a mark. The marks he leaves delineate the edges of representation, they signify a boundary where something existed for a short time. A notch is placed in time as well as space. In these actions, McKenzie is standing in for another body: he is his father’s proxy. His actions create the memorial.

Richard Gregory introduced Quarantine’s new project, When You Thought You Were (an Inbetween Time commission). The year-long participatory enterprise is “a biography of an (extra)ordinary person…a kind of wake for someone living” (www.qtine.com). Speaking of relics, memorials and celebrations, Gregory showed slides of grass, shoes, summer, dinner, play. He told the audience how, going to clear out his mother’s house after her death, before he locked the back door for the last time he had taken a jar of jam from the pantry. There and then he brought out a pot of jam and some teaspoons, placed the pot on a saucer and handed it down the table inviting the other panellists to taste it, which they did. He mentioned that blackcurrant jam wasn’t his favourite.

This is an action that suggests a form of immortality through sharing, lineage and relationships. The jam is a relic, it engages the senses and needs to be physically handled. It is concrete, it is able to be shared, it requires narration to release its meaning—it demands engagement on several levels before it can be understood; and its impact cannot be completely appreciated on a verbal level. The other thing demonstrated here was the difference between action and discourse.

“Once you are born, know you have to die.” With fireworks and intensity most of the symposium demonstrated the latter half of this equation. The achievement of many of the artists involved in InBetween Time was to give weight to the other half. Academic language needs to be able to position both these approaches along the same continuum: however much the occult needs to be revealed, so does the thing that is hidden in plain sight.

InBetween Time Festival of Live Art and Intrigue, director Helen Cole; symposium What Next for the Body, Feb 5; exhibition Arnolfini, Bristol, UK, Dec 1 2010-Feb 6 2011; www.inbetweentime.co.uk

RealTime issue #102 April-May 2011 pg. 8