Kip Williams’ Arturo Ui: Democracy’s death dance

An ironically irresistible Hugo Weaving stars in Kip Williams’ thrillingly propulsive, politically gripping production for the STC of Bertolt Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, an unnervingly funny, relentlessly incisive parable of a thug-cum-demagogue rising to absolute power. He achieves it with the complicity of a corrupt politician in an all too familiar “infrastructure government” in league with a green grocery cartel. They quickly lose control of their gangster agent of change (whose initial goal is control of the vegetable market), then the courts, the press and ultimately the democracy they have hitherto expertly manipulated.

Though casually evoking 1930s Chicago and the gangster movies that inspired Brecht, director Kip Williams and translator Tom Wright infuse the production with a sense of our own troubled times via an artfully choreographed interplay of stage performance and live video feed with drolly deft deployment of the clichéd and distorting language of Australian and international politics and economics. The effect is to render contiguous the 30s rise of fascism and the current illiberal push to the right in modern democracies. Past and present become chillingly inseparable.

This world (designer Robert Cousins) is realised within a capacious studio with open dressing and green room spaces to either side and a huge upstage screen fed by a busy camera team working initially in movie-making mode and subsequently, as politics turns overtly criminal, delivering with television news urgency, intrusive vérité shooting and propagandistic pomposity. It’s not a simple trajectory: in a funeral scene late in the work there’s a highly effective return to an intimate cinematic vision, at once compelling but perhaps also mockingly arthouse.

Dressed and masked in black, the camera crew moves about unobtrusively, the numerous set-ups with actors seamlessly realised and the tracking trajectories marvellously patterned so that Kip Williams’ direction and Justine Kerrigan’s cinematography is realised as a swirling dance of cameras and actors. The director’s well-known choreographic-cum-cinematic facility is frequently evident, for example when Ui threatens the politician Dogsborough (Peter Carroll). The latter is seated downstage, back to us, facing Ui who delivers his intimidating spiel moving on and about an axis between his victim and the screen on which we see Dogsborough writ large in anxious profile. It’s a perfect fusion of stage and screen, heightened by Weaving’s cajoling ‘dance,’ exploiting oscillation between safe distance and threatening proximity. As ever, the actor moves with great verve, from an initial pugnacious, prowling swagger to the elegant, confident stride of the demagogue. When one of his gang earlier dares to suggest how he might present himself, Ui retorts, “What the hell is ‘natural’?” Unfortunately for his victims, Ui is, in another sense, a natural, and a quick learner.

True to Brecht’s wishes, the makers admirably avoid the literalising of Ui, whether as Hitler or any other demagogue, such as Donald Trump. There is however an hilarious lesson in Hitler-ish posturing — desultorily taught by a campy failed actor (Mitchell Butel) — and a brilliant one-off sight gag involving Ui toying with but dismissing the fascist leader’s moustache and hair style. Weaving’s Ui is utterly his own man, one with limited intelligence but blessed with tunnel vision and escalating narcissistic self-belief, incanting a narrative of heroic emergence melded with paranoia. This is realised brilliantly in Brecht’s echoing of Shakespeare’s Richard III in a confrontation between Ui and Betty Dullfeet (Anita Hegh), the combative wife of the newspaper publisher Ui has had murdered.

As rain falls steadily on the funeral gathering, Ui delivers a seemingly sincere self-account, impassioned and highly convincing, replete with cosmic metaphors, bewildering an angry but vulnerable woman suddenly confronted with the unexpected. As the staging reveals the scope of the gloomy, black umbrella-ed funeral, the screen close-ups of Ui and Dullfeet provide a cinematic intensity, yielding one of the few moments of heightened realism in the production if shot with a wry arthouse verve. Weaving invests all his considerable craft in the scene, the closest we get to empathising with Ui, momentarily understanding the depth of his self-belief, however fantastical, and in himself as a performer. When we next see Ui, he is a fully realised, coolly intimidating demagogue, terrorising a vast (cinematically multiplied) public into voting for him.

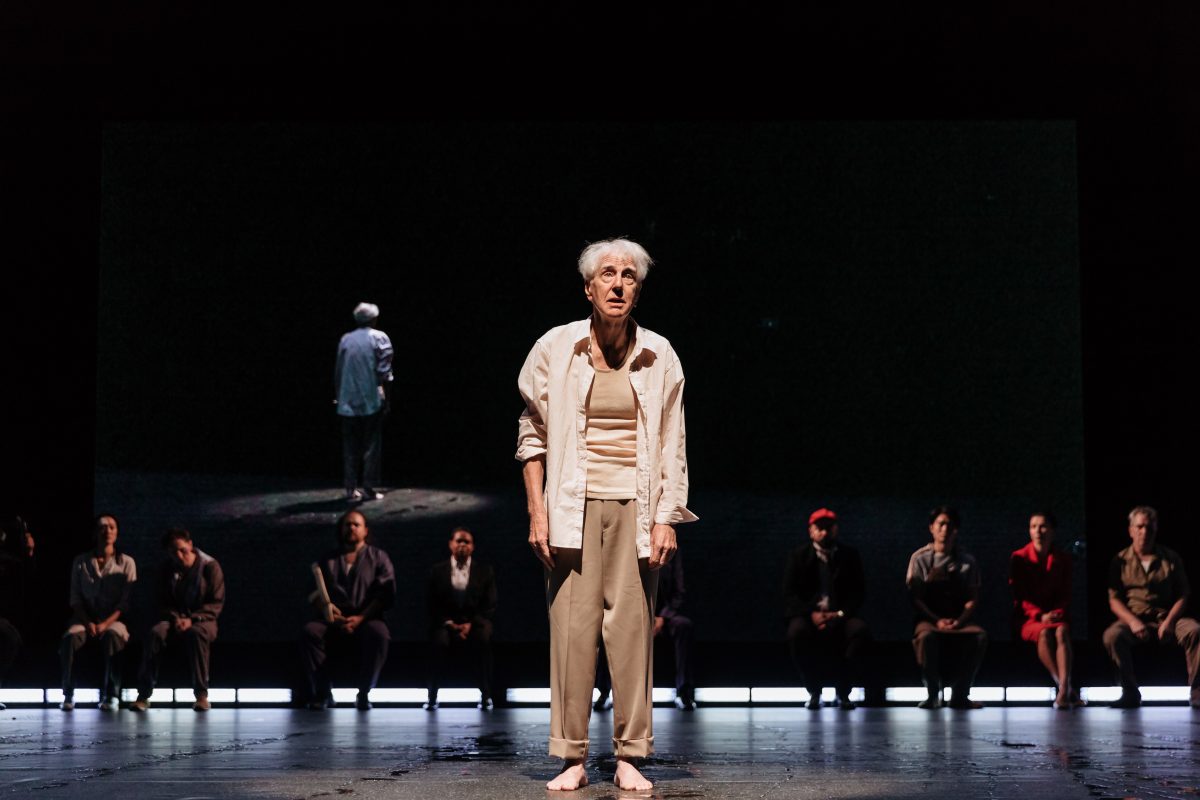

Colin Moody, Hugo Weaving (background), Hugo Weaving, Ursula Yovich and Brent Hill (foreground), The Resistable Rise of Arturo Ui, Sydney Theatre Company, photo © Daniel Boud

With Brecht’s hyperbolic text and a production excelling at the playwright’s notion of distanciation, the funeral scene is a thrilling disruption, as are the scenes in which Peter Carroll’s Dogsborough is granted a palpably intimate presence. In part driven to corruption by the need to support a son with a disability and by Ui’s thinly veiled threats directed at the child, the politician becomes increasingly guilt-ridden, creating a moral counterpoint to Ui’s career, strongly felt in a scene in which Dogsborough quietly ponders his crime and Ui’s rise while face to face with himself in a dressing room mirror, one of a number of mirror images in the production that query the nature of performance of the self.

Another scene tellingly focused on the face has Ui’s gang members spread about the stage bitterly challenging each other while a camera operator peers up between the boss’s knees. Weaving is slouched in a lounge chair, Ui’s usually hyper-animated features shut down, his heavy brow creased with introspection as he nibbles from a packet of Nobby’s Nuts. The close-up stillness exudes danger as much as comedy, indicative of a new stage in Ui’s rise, a contemplative prelude to murderously taking firm control of his own immediate realm.

Williams’ production busily fills the stage with evolving political ferment, first evident in a Senate-type enquiry scene (with Anita Hegh doing a Michaelia Cash microphone grab) overseen by Arturo Ui (think President Donald Trump’s destructive appointment of Scott Pruitt as Environmental Protection Agency Administrator). Later, a courtroom trial turns to farce as Ui’s thugs take control. Staged as a series of brief scenes punctuated with a repeated dance of pulsing spotlights as the performers reconfigure, it’s rich in comic detail, including Peter Carroll as an enthusiastic female courtroom stenographer rendered deliriously helpless as characters and cameras swirl about her.

Peter Carroll and cast of The Resistable Rise of Arturo Ui, Sydney Theatre Company, photo © Daniel Boud

Throughout, Brecht’s rich language is inflected with familiar contemporary utterances: “with respect, you’re not listening,” Joe Hockey’s “leaners, not lifters,” Ui’s plagiarising of the lyrics of John Farnham’s “You’re the Voice,” and much more — “slush funds,” “positive mindsets,” and a green grocery variation on John Howard’s “We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances under which they come.” And then there’s the fun of invention: “Even the gravy train finds itself stopping at honest stations.” The apparent silliness in the recurrence of the names of vegetables — cabbage, cauliflower, kohlrabi — in a political scenario gets continued laughs but also underlines the banality of corruption and an everyday route to power, and profit — think Coles and Woolworths’ relentless manipulation of what they pay dairy, fruit and vegetable producers.

Williams’ performers, often in multiple roles, create strongly etched characters including Ui’s gang members: Roma (Colin Moody), Giri (Ivan Donato) and Givola (Ursula Yovich). Stefan Gregory’s bracing compositions, with recurrent driving drumming and a film-noirish gravitas sound gives over to Wagner at a critical moment and a melancholy wordless chorale at another. An affecting harp piece underlines the apparent idyll of Givola’s florist shop in which Betty Dullfleet’s husband’s throat is cut by the owner. This setting is one of the few instances in the production where spectacle, multiple long strands of flowers luxuriously filling the stage, supersedes distanciation, if meeting the challenge of Brecht’s construction of the scene with two pairs of characters, oblivious to each other, wandering the shop. Another superfluity is the use of projected animated drawings — a row of poplars, a burning market building, a woman in a street. Elsewhere the production, including its deft use of intertitles, is tightly conceived and executed.

Ui’s chilling speech to the masses at the play’s end recalls Donald Trump’s dark account of the state of America in his inauguration speech. Ui spells out a vision of human savagery against which he will defend the people (dissidents are meanwhile casually shot) while offering them freedom of choice. Ui’s cool, formulaic manner recalls Betty Dullflet’s earlier defiant charge that Ui is “a meat machine trying to believe it has a self.” Now she stands beside him, defeated. The chaotic dance that prefigured Ui’s ascension is over, resolved into fascist order, overseen by a man who had declared to Betty, “I am a fanatic – I have faith.”

Our own liberal democracy is under less corrosive threat than that depicted in Brecht’s parable, and is therefore easy to underestimate or ignore, while in Turkey and the newer democracies of Eastern Europe human rights are rapidly eroding. It’s surprising and fascinating that an emerging wing of the American Democrats is the defiantly titled Democratic Socialists of America. In Australia’s parliament, we have proliferating right wing party representatives, a conservative often reactionary Coalition government and a Labor Party largely driven by its right wing. How long will it be before a defiant assertion of democratic socialism emerges in Australia to defend and build on public utilities and rights? Better that than a slow dance to death. But it is resistible.

–

Sydney Theatre Company, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, writer Bertolt Brecht, translator Tom Wright, director Kip Williams, performers Mitchell Butel, Peter Carroll, Tony Cogin, Ivan Donato, Anita Hegh, Brent Hill, Colin Moody, Monica Sayers, Hugo Weaving, Charles Wu, Ursula Yovich, set designer Robert Cousins, costume designer Marg Horwell, lighting designer Nick Schlieper, composer, sound designer Stefan Gregory, cinematographer Justine Kerrigan; Roslyn Packer Theatre, Sydney, 21 March-28 April

Top image credit: Anita Hegh, Hugo Weaving, The Resistable Rise of Arturo Ui, Sydney Theatre Company, photo © Daniel Boud