laurie anderson: we are meaning machines

gail priest: 2013 adelaide festival

Laurie Anderson & Kronos Quartet, (l-r) Hank Dutt, Jeffrey Zeigler, Laurie Anderson, John Sherba, David Harrington

photo Jay Blakesberg

Laurie Anderson & Kronos Quartet, (l-r) Hank Dutt, Jeffrey Zeigler, Laurie Anderson, John Sherba, David Harrington

IT SEEMS THE 1986 ADELAIDE FESTIVAL WAS RATHER MIND-BLOWING FOR MANY AUSTRALIAN ARTISTS. THIS IS HARDLY SURPRISING GIVEN THAT THE FESTIVAL, DIRECTED BY ANTHONY STEEL, FEATURED SOME OF THE MOST INFLUENTIAL ARTISTS OF LATE 20TH CENTURY: PHILIP GLASS, THE WOOSTER GROUP, JAN FABRE AND LAURIE ANDERSON.

For me, coming into the performance scene in the early 1990s, Anderson’s multimedia concert at that festival had become legendary and while she has since appeared in Australia (at least four times in Sydney), none of these concerts has been able to match the scale, whether real or apocryphal, of that 1986 event. (Of course at Vivid 2010, we did get the live-in experience of Anderson as co-festival director with Lou Reed, appearing in several concert manifestations). Nonetheless, Anderson has still impressed many of us in the next generation, mainly via recordings, with her idiosyncratic compositional style but most particularly her unique brand of whimsical profundity—everyday observations, personal stories and reconfigurations of philosophy that she can deftly turn into serious insights into life and mortality, or incisive criticism of American proselytising, warmongering and the toll of unchecked capitalism.

Adelaide Festival comes to the rescue again. In 2013 Australian fans will enjoy perhaps the most comprehensive picture to date of Anderson’s oeuvre, not just as a poet/musician, but as a truly multimedia and multimodal artist via three quite different events. Anderson will present the results of her musical collaboration with the Kronos Quartet; she will perform her latest spoken word piece, Dirtday! and also exhibit a selection of installation and visual art pieces from various stages of her career at the Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum.

I had the privilege of speaking via phone with Laurie Anderson who was in Los Angeles rehearsing with Kronos Quartet on their new, as yet untitled work.

kronos collaboration

You’re certainly making the long haul trip worthwhile, presenting three works in Adelaide. Can you tell us about the Kronos collaboration?

This is the third time that we’ve gotten together to work on it and it’s pretty inspiring. These people can really play. For example, some of the sounds that will be in it come from a keyboard that has a lot of information stored on optical discs. It sounds very lo-fi and very sort of sad, like some kind of old ice skating rink from 30 years ago. Playing with sounds that have a quality like that—of scratchiness and eerie otherworldliness—is something that they can do in their sleep. It’s really amazing how they can adjust their playing into that world.

So the piece uses text and stories but it’s triggered by their playing?

Yes it’s some software that I wrote. Imagine superfast subtitling that’s triggered by sound—and different aspects of sound, the note you’re playing or how loudly you’re playing it. You’re listening and reading things and you suddenly realise that you can read 10 times faster than you thought. Which is really kind of exhilarating. Also new alphabets suddenly get introduced and you realise you can read these new alphabets also…

The meaning of a work of art is wrapped in colours and sounds and whatever material the art is made of and the audience looks at it or listens to it and unwraps the meaning from those works—aha there it is! In this case it’s really about that search…I’m hesitating because it sounds really pompous to say it, but we really are meaning machines. Walking down the street we are always trying to look for a resonance or look for things that mean something. And so this is about that act itself. Suddenly you catch yourself looking for how systems work and then you realise that you can read this certain kind of code.

So is it all text on screen?

No there’s spoken text as well. For example, imagine you are listening to somebody speaking and the words that you are hearing are the words that you’re seeing and that works for a while and gradually other kinds of icons start invading the written text. For example the graphics sign for ‘staircase’ starts becoming the word ‘snake’ and you realise very quickly that you can read that. I’ve always wanted to actually design an alphabet. It’s weirdly about different kinds of music notation too because some of the alphabets really begin to look like music…So it’s really an interesting system to be working with. I’ve never tried anything like this before.

dirtday!

I understand Dirtday! was inspired by the Occupy movement. I’ve heard you mention that you were trying to make a music-driven piece and that the words took over. How do you negotiate your need to make music and your need to write words?

It’s always a bit of a fight. I’m not sure why one begins to dominate but I’ve never done a piece in which there’s the complete balance between music and text. I think this is also because I really like the relationship of spoken words to music as opposed to lyrics or rhymed words which I find are usually kind of static. There’s the ‘moon in June’ rhyming and after that it becomes kind of almost silly. When I hear really wonderful lyrics that have really strange rhymes I like it very much, but I’m not very good at it myself. So I don’t do that very much.

Dirtday! is based on quite a political topic. Do you feel like the times are forcing you to become more forthright with your messages?

Sometimes things are very explicit. I usually shy away from that because I’m so afraid of being preachy, but once in a while it’s just too tempting not to comment specifically on what’s going on.

Does this have visual material as well as your spoken and performed music?

A very little bit. Basically it’s one very long mental movie and I find working in that way just really exhilarating. When you hear a story you really begin to build up a visual world, and it’s your own world in the way that your dream world is your own world. I’m just using words to do it so it’s very much a collaboration with the audience in that way.

the language of the future?

Laurie Anderson, Duets On Ice (1976)

photo Canal Street Communications

Laurie Anderson, Duets On Ice (1976)

You’ve always managed to maintain such a high-level of experimentation but at the same time your work is incredibly accessible. Is that a conscious choice or is it just the way your experimentation plays out?

For a long time I really didn’t want to repeat things. That of course became impossible and exhausting. As soon as you’d invent something you’d have to invent something else and that just seemed like a completely artificial way of treating material and it meant that also you wouldn’t be able to get very good at presenting it. So eventually I got over that very strict way of looking at the world. I was like that because I didn’t like the concept of theatre, it seemed too mannered, so I decided to experiment with every work. That’s changed over the years but I still tend never to do old things. I’ve maybe done two tours in my life in which I played old material. It was great fun to do that and I’m not sure why I don’t do that more often. Maybe I’m just talking myself into doing one right now.

Is the exhibition The Language of the Future something of ‘greatest hits’ show?

It’s not a retrospective, it’s a few chosen works. One will be a very old work from the 70s when we did music in really old broken-down warehouses using equipment that was just falling apart [The Electric Chair see video]. Then there’s going to be a visual piece that has a funny resonance because it looks like that sound piece but it’s serene and purely visual. And then there’s some story pieces as well and some installations and some photo works.

You’ll even be performing your famous early work Duets on Ice.

Yeah, that’s going to be fun. That’s from 1975 and it was a show that was done outside on the street using the violin that I made that played by itself. There were speakers inside and you would play duets with it live. Because it was the kind of show that could theoretically go on forever—it didn’t have a beginning or an end, it was just a loop—I thought what’s the clock here? When is the show over? So I set a kind of time mechanism: I wore some ice-skates with their blades frozen into blocks of ice so that when the ice melts and you lose your balance the concert’s over. Sometimes that took a very long time. What’s the weather like in Adelaide?

Adelaide is notoriously hot and dry.

Well, it’ll be a short show!

* * *

other adelaide festival highlights

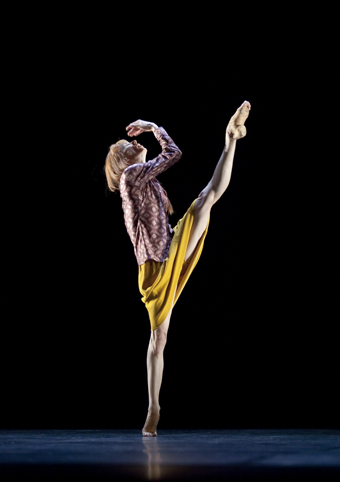

Sylvie Guillem, 600 Miles Away

photo Bill Cooper

Sylvie Guillem, 600 Miles Away

The 2013 Adelaide Festival program looks like it might come close to the mind-blowing status accorded to the 1986 program. Other highlights include 6000 Miles Away with Sylvie Guillem choreographed by Mats Ek, William Forsythe and Jirí Kylián (RT106); Hotel Modern’s confronting Kamp (RT96); several interactive works by Ontroerend Goed whose The Smile Off Your Face is a quiet classic (RT89); Wim Vandekeybus and Ultima Vez’s What the Body Does Not Remember (Vandekeybus was possibly in Jan Fabre’s work at the 1986 festival); a concert by renowned US music producer Van Dyke Parks; and three nights of experimental audiovisual works presented by the Unsound Festival (Krakow/New York) including Ben Frost and Daniel Bjarnason’s Solaris with film manipulations by Brian Eno and Nick Robertson (RT103). There’s a healthy quota of Australian companies such as Erth, Brink, The State Theatre Company, The Black Lung Theatre and Whaling Firm (see RT111) and a new work from Adelaide choreographer Larissa McGowan.

Adelaide Festival: Laurie Anderson with the Kronos Quartet, Adelaide Festival Theatre, March 2; Dirtday!, Dunstan Playhouse, March 3; The Language of the Future, Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art, March 1-April 19; www.adelaidefestival.com.au

Laurie Anderson and the Kronos Quartet will also be performing their collaboration at the Perth International Art Festival, Feb 27. See also Keith Gallasch’s interview with Perth Festival guest, US media artist Jim Campbell; www.perthfestival.com.au

RealTime issue #112 Dec-Jan 2012 pg. 5