layering the asian-australian connection

jonathan bollen: 2011 ozasia festival, adelaide

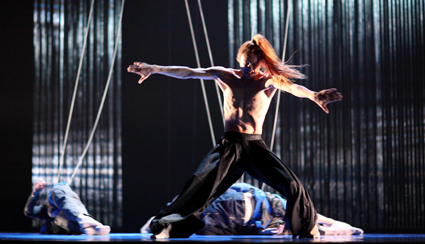

Kaiji Moriyama, Escape, Leigh Warren + Dancers

photo Tony Lewis

Kaiji Moriyama, Escape, Leigh Warren + Dancers

FOR THE FIFTH OZASIA FESTIVAL, THE ADELAIDE FESTIVAL CENTRE AND LEIGH WARREN AND DANCERS PRESENTED DREAMSCAPE, A DOUBLE BILL STITCHED TOGETHER BY LAMINATIONS OF TIME, PLACE AND CONNECTION. ESCAPE IS A WORLD PREMIERE, CHOREOGRAPHED BY WARREN IN ASSOCIATION WITH JAPANESE DANCER-CHOREOGRAPHER KAIJI MORIYAMA. DREAM TIME IS A REVIVAL OF A WORK BY CZECHOSLOVAKIAN CHOREOGRAPHER, JIRÍ KYLIÁN, FIRST PERFORMED IN 1983 AT THE NEDERLANDS DANS THEATER WITH WARREN IN A LEADING ROLE.

Both Escape and Dream Time are set to music by Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu. Australian pianist Simon Tedeschi plays on stage with the dancers in Escape. In a program note, Kylián explains how he met Takemitsu at a dance festival on Groote Eylandt in the Gulf of Carpentaria.

In Escape, three dancers—Bec Jones, Kevin Privett and Jesse Martin—are dressed in cargo pants and sleeveless hoodies. Suspended from above, they abseil into the performance. As they plumb the depths, their exertions are anchored in the vertical. As they sink and rise in clusters, their limbs extend and pivot round their torsos. The Australian dancers have descended into darkness, recalling Warren’s visit to the Akiyoshido cave in Japan. Down there Kaiji Moriyama emerges from within. His fine exploratory gestures reach forward, through the ropes and broken wires that designer Mary Moore has stretched and sprung in tangles. At this depth, Moriyama’s dancing adheres closely to the music, alive with sensitivity and intuition. Echoes bounce and relay between Tedeschi’s sound and Moriyama’s action. Their synchronicity is reminiscent of another nature underground, the speleogenesis of the underworld.

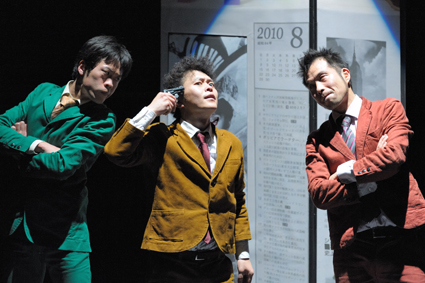

Dreamtime, Leigh Warren + Dancers

photo Tony Lewis

Dreamtime, Leigh Warren + Dancers

By contrast, the choreography of Dream Time extends across the surface. Five dancers—Lisa Griffiths, Bec Jones, Kevin Privett, Adam Synnott and Lizie Vilmanis—strike poses in a barren landscape. They give each other space to dance in pas-de-deux and trios. They yield to the lyricism of locomotion as they reach and sweep across the stage. While the shimmer of the landscape’s horizontal extension is as tensile as Takemitsu’s music, the choreography’s claim to territorial belonging is as tendentious as Martha Graham’s “appetite for space” in Frontier or Appalachian Spring. Warren writes that “it is wonderful to have a chance to share some of my dancing history with the dancers and an audience.” The two works of this double bill are intricately connected through layers of artistic collaboration. The historical transition between the two is recounted by their choreographic distinction: the breadth of territorial expansion in Dream Time is replaced with the depth of interior reflection in Escape.

In Lieu at the Space Theatre saw transient reflections and intangible energies sustain intimate intensities at ground level. The work of Australian-born choreographer and dancer Ade Suharto extends from her dance training at the University of Adelaide to the tari putri style of Javanese dance and beyond, across the choreographies of the Asia-Pacific to Taiwan’s Lin Hwai Min of Cloud Gate Dance Theatre and Lemi Ponifasio’s MAU from Aotearoa/New Zealand. In this performance, Suharto works with composer and musician David Kotlowy who leads Gamelan In Situ through a set of contemporary compositions. Like the rhythmic repetitions of the gamelan, Suharto’s choreography develops interest and complexity through measured repetition. As actions are repeated, their memory is transformed. There is a sense of journey through the dances—patterns of arm to head, of foot to knee, are relayed from there and replayed here.

Suharto dances alongside a long-form trapezoidal screen extending diagonally across the space. Mawarini’s shadow puppetry on the screen is breathtaking in its intricacy and innovation. The shadows—like the dancing and the gamelan—are relieved of responsibility for delivering character or plot. But they encapsulate an evolving world of organic forms which flicker, slide and fade. As a production, the emphasis of In Lieu was on the music. The presence of six gamelan musicians on stage gave the performance its energetic core. Some difficulties in balancing the lighting with the shadows were not entirely solved. Visual interest was sometimes flattened when the dancer lacked the energy of light. Or maybe what I wanted were the visual echoes of other dancers to refract the polyrhythms of the music. OzAsia confronts us with economies of scale that constrain the production of Australian performance. Shaolin Warriors, the crowd-pleaser from China at the Festival Theatre, syndicated its spectacle of martial arts across a cast of 22. The geometric patterns of Suharto’s choreography deserve to be extended beyond the solo. I would like to see their rhythms stretch and echo across an entire dance ensemble.

Continent, CAVA, OzAsia 2011

courtesy OzAsia

Continent, CAVA, OzAsia 2011

An individual’s desire to transcend the uniformity of the ensemble drives each of the protagonists in two parables of modern life. In Continent from Japanese mime company, Cava (pronounced sah-va), a jobbing writer’s imagination takes flight, as he struggles to rise above the challenges of the ordinary and find a publisher for his work. A working girl, who makes him tea and brings him lunch, at first distracts him from his writing. She then takes to the typewriter and contributes to his story. But the system is corrupt. He competes with other writers for the publisher’s interest and commission, but submits his script on its merits alone, without the requisite bribe. The writer and his girl—both bespectacled like the Coen Brothers’ Barton Fink—set out against the odds to overcome conformity with the romance of their animated imagination.

Continent is enacted with lightness and precision by five performers; writer and director Kazuaki Maruyama takes the leading role. He pitches the ensemble’s rhythmic mime against a perfect soundtrack of sentimental film-score music wrought with interruptions and cartoon-ish sound effects. The production is colourful and bright. Maruyama’s dramaturgy bears a modernist nostalgia for the mechanisms of the mid-20th century, The work features a portable set that opens and shuts, mime techniques for animating machines and hand-manipulated puppet-props. There is something light and airy about the execution of the piece. Its romance is enchanting.

Rhinoceros in Love, National Theatre of China, OzAsia 2011

courtesy OzAsia

Rhinoceros in Love, National Theatre of China, OzAsia 2011

By contrast, the romance of Rhinoceros in Love is resolutely existential. This “modern classic” from the new China is now more than a decade old. In its 10th anniversary revival for the National Theatre of China, Meng Jinghui directs Liao Yimei’s play with an ensemble cast of young and energetic actors. The story is not particularly striking. The rhinoceros provides an outlet for a young man’s frustrations with love. His would-be lover does little more than offer her rejection. There are soliloquies and scenes of violence, emotional frustration and release. The set is black, hard-edged and cold: mirrors lend its surface depth, cold water spreads across the floor. The metaphor of love’s frustration is extended into space. The play’s existential romance depicts a young man’s individualistic aspiration for love’s promised self-actualisation. But rather than the tortured couple, it was the ensemble—the actors performing as the couple’s cohort of friends—who communicated the pleasures of the piece. (See Douglas Leonard’s review of Brisbane Festival)

The wet depths of the couple’s raw emotion were less compelling than the frontal sarcasm of the actors’ ensemble. With the slick confidence of Chinese television game-show back-chat, their dorm-room gags, sexed-up tricks and dance routines of bubble-pop hip-hop forged direct connections with the audience. It is difficult to capture just how ‘now’ and ‘of the moment’ this production’s crowd-engaging vision of drama felt. Students at Her Majesty’s Theatre in Adelaide roared with pleasure at being captured by the work and its depiction of themselves in its predicament. But ultimately Rhinoceros is ambivalent about love. The couple’s passion is exhausting. Their reward remains elusive. The performance rides upon the power of the ensemble to conjure solidarity from audience response.

Dreamscape: A Double Bill, Leigh Warren and Dancers, Dunstan Playhouse, Sept 2-4; In Lieu, performers Ade Suharto, David Kotlowy, Mawarini, Gamelan In Situ, Space Theatre, Sept 6-7; Continent by Cava, writer, director, performer Kazuaki Maruyama with Takaaki Kuroda, Hiroyuki Fujishiro, Thin Hosomi, Ykiko Tanaka, Space Theatre, Sept 15-17; National Theatre of China, Rhinoceros in Love, writer Liao Yimei, director Meng Jinghui, Her Majesty’s Theatre, Adelaide, Sept 15-17

RealTime issue #106 Dec-Jan 2011 pg. 6