Life and death, and the membranes inbetween

Urszula Dawkins, semipermeable (+), SymbioticA

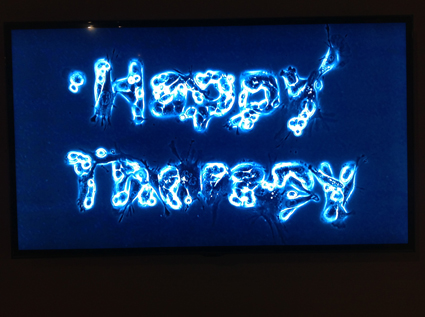

Verena Friedrich, Cellular Performance, 2011-12, still

From the recognisably organic form of a lab-grown tree-fungus dress to slick, cold-steel missiles like infiltrating spores, the works in SymbioticA’s semipermeable (+) elicit both pleasure and discomfort as they push science, and ‘wet biology practices’ in particular, towards and through a range of conceptual limits. I reached semipermeable (+) after a stroll through Experimenta’s Speak to Me, sharing the Level 4 Powerhouse space. Stepping from the family-filled, playful halls of twittering mechanical peacocks and kaleidoscopic turntables into a room full of cool glass, metal clamps and tubing was indeed like slipping through a membrane.

WA’s SymbioticA is world-renowned for its emphasis on hands-on collaborations between artists and scientists; for pushing the bounds of biotechnology and prodding with equal vigour at its ethical limits. While a few works in semipermeable (+) eschew the lab-ware in favour of traditional installation, the overall aesthetic is strongly grounded in the microscopic, the genetic, and forms of living (or dead) containment.

A hallmark of SymbioticA is the work of founder Oron Catts with Ionat Zurr, and it’s great to see their now-iconic Victimless Leather (2004) here – a living, miniature coat grown from continuously dividing human and mouse cell lines, and ‘fed’ by an automated nutrient drip. Alongside it is a new work by Catts, Zurr and Corrie van Sice, The Mechanism of Life – After Stephane Leduc (2013). Pointing to Leduc’s 1911 theory that life is merely a chemical process, a custom-built apparatus ‘prints’ blobs of ‘protocells’ into a petri dish, the inks and dyes spreading to form hexagonal arrays that miraculously ‘grow’ before your eyes.

From life, to un-life: a dead cane toad makes music – albeit very, very quietly. It’s a sort of fuzzy, low, soft sound, usually inaudible, but processed for the human ear in Cat Hope’s Sound of Decay (2013). The corpse itself is a vaguely disturbing form almost obscured by the condensation that lines the walls of its sealed glass container, and as such evokes death and a kind of elongated time-scale more surely, perhaps, than a clear view.

German artist Verena Friedrich takes the endless promises of the cosmetic industry and manipulates skin cells to tout the benefits of ‘cosmeceuticals’, displaying the results in a video installation titled Cellular Performance (2011–12). Rendered in electric blues, stark whites and rich blacks, the cells with their tree-like appendages and neon brightness form words: natural living things infused with a decidedly ambiguous dose of consumer culture.

Nigel Helyer, Supereste ut Pugnatis (Pugnatis) ut Supereste (SPPS), 2013 (installation, detail)

Almost opposite Friedrich’s micro-billboards, Nigel Helyer’s slick, steel, contaminant-bearing missiles evoke both fertilisation and all-out biological warfare at macro scale. Intricately detailed, their crafting is both sci-fi and organic, reminiscent of Maria Fernanda Cardoso’s Museum of Copulatory Organs (Sydney Biennale, 2012). Carrying SPPS – “an omnisexual bacterium, ingesting histories and narratives that connect through powerful metaphorical bonds” – Helyer’s missiles have a disturbing ‘biological’ appearance, less like bombs than seed carriers shot across borders with the aim of catching their sharp fins on unsuspecting hosts.

Several further works in semipermeable (+) employ the use of cultures and cell lines: foreskin cells reverse engineered to create a functioning neural network (Guy Ben-Ary and Kirsten Hudson); a human/canine hybridoma (Benjamin Forster); fluorescently transformed embryonic kidney cells; virally ‘tattooed’ skin cells (Tagny Duff). These explorations of ‘what we can do’ with biological matter feed an artistic space that holds many conflicts – and there’s a strong sense of the (desirable or undesirable?) ‘semipermeability’ of a natural domain whose borders were once considered impenetrable.

The ubiquity of sealed glass cases, plugged flasks and contained fluids – all necessary for containing the biohazards or fragile life-forms within – has a certain irony, given the theme of the membrane and its qualities of porosity, transfer and exchange. In semipermeable (+), we are locked out of life’s processes, except when they are simulated. And this, in a sense, is telling: the rigidity of our control over nature demands that we’re protected from the renegade species, from the contaminant, from the challenge to our integrity – whether it’s from biohazard or infiltrating thought. The mix of sterile glass and proliferating life (or death) within is potent; because ultimately the ideas that emerge around this work are what slip across our perceptive borders, infecting us whether we touch, breathe, brush up close, or not.