life behind a curtain

keith gallasch: maya newell’s richard, angie abdilla’s wanja

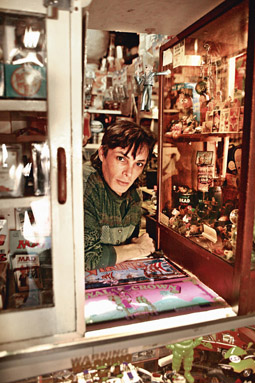

Richard Blackie

photo Steve Bacon

Richard Blackie

RICHARD, THE MOST INTERESTINGEST PERSON I’VE EVER MET, IS A FUNNY-SAD DOCUMENTARY OF THE LIFE OF AN IDIOSYNCRATIC INDIVIDUAL—RICHARD BLACKIE, 41 YEARS OF AGE, A FORMER AND VERY CONVINCING MICHAEL JACKSON IMPERSONATOR, BONSAI GARDENER AND TOY COLLECTOR OF 20 YEARS, WHO BECAME AN ANTIQUE AND VINTAGE TOY SHOP OWNER AND WHO SUICIDED BEFORE MAYA NEWELL’S FILM WAS COMPLETE. SHE WAS 17 AT THE TIME AND A STUDENT AT THE SYDNEY FILM SCHOOL AND UNTIL PERSUADED OTHERWISE, THOUGHT THERE WASN’T ENOUGH OF RICHARD’S LIFE IN HER FOOTAGE TO MAKE A COMPLETE FILM. HOWEVER IT PREMIERED AT THE 2007 DIRECTOR’S FORTNIGHT IN CANNES, IS NOW AVAILABLE ON DVD AND DESERVING OF A WIDE AUDIENCE.

The power of the film is generated by the dynamic between how little we learn about Richard (Newell eschews standard documentary story-telling and there are no interviews with her subject’s friends or acquaintances of whom there were possibly few) and the feeling that we’re building a very strong impression of an intensely private and secretive man—narcissistic, obsessive, authoritarian, but all in the nicest possible way. This is compounded by Newell’s approach, which is informal, patient and gently probing, and Richard’s response which is cautious and evasive, but at the same time characterful, often droll and very immediate. He’s also very controlling, visibly determining the duration of a conversation or deliberately keeping his distance from the camera. At one point early in the film he takes the camera and turns it on the filmmaker, a moment illustrating his playfulness, authority and the acknowledgment perhaps of a creative partnership, and one where, with unconscious prophetic irony, Newell shyly promises to make his collection of toys live on. He wants this film—of “the most interestingest person you’ve ever met”—to be made.

After Richard’s death well-known poet and screenplay writer Billy Stoneking Marshall told Newell, who felt her project was lost, that she had the makings of a film not so much about Richard as her relationship with him. Not surprisingly then, except for the brief glimpse of a cemetery at the film’s opening, a few shots of the immediate front of Richard’s shop and, much later, his doomed foray into an auction house, there’s no sign of the outside world save the visit of an occasional customer or postman. Tellingly, you’ll find some wider shots of the street, and some plainer statements of fact (Richard telling Newell that he was an orphan), in the out-takes on the DVD. Clearly Newell and her editor have focused the film tightly on Richard’s closed world and his meetings with the filmmaker, and cleverly and effectively so for a film which, on the surface, displays so little artifice.

This interplay of immediacy and the witholding of information and speculation is amplified by frequent filming of Richard in hand-held close-up or medium shot in the crowded confines of his shop, in narrow corridors, or perched by display cases having a smoke, or with his small dogs in his tiny kitchen, the camera looking around the corner or over his shoulder. The viewer constantly reads the strange, handsome architecture of Richard’s face—male, female, Aboriginal (compounded by occasional touches of Aboriginal English), the result of surgery? But if information is short, emotion is not, and although not expressed overtly we are witness to Richard’s growing anxieties about the failure of his shop and the need to sell his beloved toy collection (to get himself out of debt). He dreams of creating a museum from his remarkable collection (with which we grow steadily and fondly intimate), but he can’t get local council support. He’s momentarily buoyed by the prospect of profit from the auction, but, at around that time, in his sleep he smothers the one puppy he was going to keep from a new litter. The film’s most emotionally demanding passage is of Richard placing the body of the dog in box, adding Newell’s name to the inscription, and then burying the box in his backyard. Here, there’s restraint on both sides of the camera and we feel we’re in the grip of a chilling inevitability. In the notes accompanying the DVD, Newell writes that she had no idea that Richard would kill himself. That only became clear as she looked back over the five hours of footage she had recorded over three months and is subtly built into the film’s structure. The youthfulness of Newell’s voice, the naivety of some of her early questions and the wisdom evident in her final voiceover make Richard an unusual rite of passage film. Early on, Richard tells Newell, “I become under a code in life where you don’t reveal your life too much, you know. You’re more behind the curtain for what you do. So you’re very very privileged.” And thanks to Newell, so are we, because she has lifted the curtain just a little to reveal a fascinating, seriously funny, complex person, and asked that perplexing question, can we ever foretell a sucide?

Angie Abdilla’s 25-minute documentary Wanja is, at one level, a fond eulogy for Wanja, a blue heeler with an intense dislike for police officers. At another, it’s a lament for a dying community, Redfern’s The Block, in inner suburban Sydney. The interviewees are mostly Aboriginal elders, some bitterly hostile to the police, suspecting them of having killed Wanja. One man blames his own community for its troubles as much as the police, not least because of drugs, another the government for eliminating a large number of houses and reducing Aboriginal control of the area. These brief statements are insterspersed with re-created images of Wanja in basic blue-tinged video, wandering the streets like a phantom guardian of the community, and other footage that lingers recurrently over the pruned back Block, wasted houses and the art and graffiti of Aboriginal occupation on building walls. Other footage constructs the imagined view from the police surveillance cameras atop the tall building diagonally opposite The Block. Save for its moments of anger, Wanja is a gentle, carefully paced weaving together of points of view (personal and cinematic)—a meditation on a culturally signficant but sad place.

Richard, the most interestingest person I’ve ever met, a film by Maya Newell, 2007, Siren Visual DVD, 52mins, www.sirenvisual.com.au; Wanja, writer, director Angie Abdilla, producer Tom Zubrycki, editor Leah Donovan, sound design David White, cinematography Kim Batterham, Sean Bacon, 2008, 25minutes.

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg.