Lightning conductor: IHOS' Tesla

Susanne Kennedy

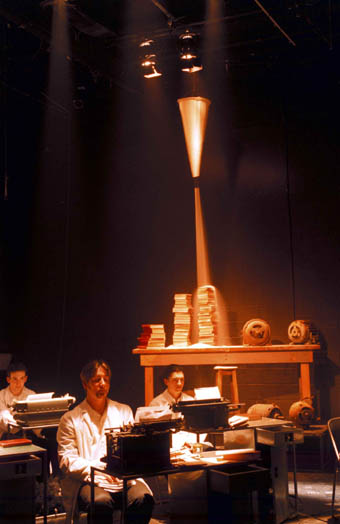

IHOS, Tesla

photo Bruce Miller

IHOS, Tesla

Constantine Koukias, composer and Artistic Director of IHOS Music Theatre, has a thing for big sheds. It’s one reason for his repeated staging of epic scale operas. His Hobart based company is currently gearing up for its production of Tesla, Lightning in his Hands, an opera with 51 performers, which opens the Ten Days on the Island festival on March 28. Commissioned by the West Australian Opera the work was originally performed in a developmental stage by IHOS Music Laboratory in Hobart in 2000 (RT 41, Feb-March 2001).

Nikola Tesla, the opera’s protagonist, invented the Alternating Current (AC) electrical system all modern cities use today. On the surface he’s a little known, vastly under-credited figure, though, Koukias has been surprised to learn how many people have come across his brilliant and colourful subject, either through science-based study, practising a trade that evolved from Tesla’s discoveries, or simply through wide reading. Because of this we can expect a fair quota of engineers, science boffins and sparkies in the audience alongside IHOS devotees.

Tasmania’s biennial Ten Days… festival celebrates island cultures from around the world, so audiences attending Tesla will be even more varied than usual. With this in mind, Koukias has tried to create something for everyone while remaining true to his vision. There are what he calls the ‘blockbuster elements’, including an ingenious representation of Niagara Falls using ‘lots of sand’; and the scale of the production, alone, will draw some who might otherwise give opera a miss.

There is plenty to keep them occupied, not least a large Tesla Coil on leave from Scienceworks in Melbourne. This mechanism—or high frequency step-up converter, to be precise—creates voltage that comes off its top as a corona, after striking the Faraday Cage that encloses it. The result is effectively a bolt of lightning.

Organisations such as Telstra have long emulated this model to test their telecommunications systems in the event of actual lightning. The Coil takes 2 people 7 days to set up, and in charge of this highly specialist process will be Telstra’s retired head physicist—the aptly named Dr Lightning.

The potential impact of the lightning generated in the show is widespread and must be regulated closely. The Marine Board will be notified just before the Coil performs its magic, as radars might be sent haywire. It’s not surprising, then, that pacemakers and other internal magnetic devices could be affected. Because of this Tesla is contemporary in more than style—it bears a health warning referring people with any form of electric, mechanical, magnetic or metallic implant or prosthetic to an information line before purchasing tickets. The level of noise or thunder generated by the Tesla Coil alone could interfere with any of these devices, causing medical complications.

When I met Koukias, he spoke with the clarity of a screenwriter who has whittled his story down to its bones and finally to one simple idea: Nikola Tesla dreamed of giving free energy to the world. It is this desire which influences many events in his life: the long-term struggle with Thomas Edison who swindled him out of patents and money; his alliance with George Westinghouse on projects including the Niagara hydroelectric plant and phased AC electricity; and ultimately the seizure of his life’s work by the FBI.

Tesla invented fluorescent bulbs and speedometers for cars. He discovered X-rays and the basis for radios, stereos and computers—in all, the foundations for most of modern industry and technology. Yet some of Tesla’s inventions are wrongly attributed to Edison in the Smithsonian Institute and patents are still being turned over to his estate.

Tesla’s character is as extraordinary as his inventions: more comfortable in the company of pigeons than women, he named his main 2 (of 30) secretaries Miss 1 and Miss 2. His affection for feathered vermin is all the more surprising given his terror of dirt. He was a close friend of Mark Twain and himself a beautiful writer.

The opera’s design is elemental—all sand, (a ream of) paper, (gothic quantities of) dry ice, steel (generators), (a flock of) pigeons and, of course, lightning. Yet for all of its ‘blockbuster’ volume, scale and explosiveness, Tesla has a minimalism about it, reminiscent of Koukias’ first opera Days and Nights with Christ. The music often reflects this simplicity, holding the audience in a loop of one-word choruses; at one point, savouring and playing with the word ‘electricity.’

In a venue the size of a few urban warehouses, the audience’s focus must be deftly managed. This is done via directive lighting and the selective use of speakers—with the audience seated either side of the action, as if at a tennis match.

Clusters of glowing light bulbs held forth like a chalice or host at high mass, cages, typewriters, lockers and lamp-lit desks carrying Van der graff generators recreate an intense and surreal laboratory. Haunting images of Tesla’s inventions, including the electric chair, are projected throughout and the Niagara Falls project becomes a gorgeous conclusion to the first act—with the Falls projected onto a stream of falling sand, through which the chorus exits. In the spirit of Tesla, the work is innovative in both sound and set design.

What Koukias likes about big sheds is that things can seem so close, or really far away—creating a cinematic distance. But most of all, the sound is beautiful. Think of the resonance of a cathedral sermon or hymn, even for the unconverted. Music has to be written specifically for large spaces. Crisp and succinct doesn’t work, so Koukias has gone with a lyrical and melodious approach, wed with a chamber ensemble that includes bassoon, oboe and theremin—a nice counterbalance to the deliberate harshness of other aspects of Tesla’s soundscape. The composer has used Tesla’s own writing for some of the opera’s lyrics, and Dvorak’s New World Symphony is alluded to given the composer’s close friendship with Tesla.

What was it about a mad pigeon-loving inventor that inspired a composer to construct one of his famously big operas? Lightning was probably the starting point, Koukias suggests, and that famous photo of Tesla sitting at his desk, oblivious, while the Tesla Coil sets off its spectacular explosions behind him. These lead Koukias to the sad and heightened story that so lends itself to opera.

Tesla. Lightning in his Hands, IHOS Music Theatre, music & director Constantine Koukias, technical director Werner Ihlenfeld, conductor Jean-Louis Forestier, production design Maria Kunda, sound Greg Gurr, artist in light Hugh McSpedden, lighting Damian Fuller, costumes Feruu Seljuk; Ten Days on the Island, Princes Wharf No. 1 Shed, Castray Esplanade, Hobart, Mar 28-Apr 1 www.tendaysontheisland.org

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 44