listening to history

jon rose’s 2007 peggy glanville-hicks address

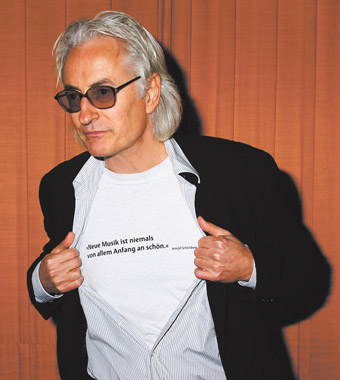

Jon Rose, “Neue Musik ist niemals von allem Angfang an Schön” (New music is never very nice at the beginning)

THE FOLLOWING IS AN EDITED VERSION OF THE 2007 PEGGY GLANVILLE-HICKS ADDRESS BY VIOLINIST, COMPOSER, FREE IMPROVISER AND INSTALLATION ARTIST JON ROSE FROM THE ANNUAL FORUM PRESENTED BY THE NEW MUSIC NETWORK. THE COMPLETE PAPER CAN BE READ ON THE NETWORK’S WEBSITE AND WILL BE THE BASIS FOR A CURRENCY HOUSE PLATFORM PAPER IN 2009.

The full title of the address is Listening to History: some proposals for reclaiming the practice of music. Rose frames his witty and passionate argument for a wider and deeper embrace of music in everday life, education and cross-cultural relations in terms of Australian Aboriginal culture past and present, and within that reflects on the European incursion and its instruments—from the piano to the computer (sadly, Australian pioneering here was not capitalised on). Our edited version focuses on the mainframe of Rose’s argument about the relationship between black and white cultures. His short history of electronic music in Australia can be read in the full version of this address online. We’ll look at this history in a later edition of RealTime.

* * * *

Last year at a Sydney University, a musicologist observed, “Everybody knows that music in Australia didn’t really get going until the mid-1960s.” Significantly, this gem was spoken at a seminar that featured a film about the Ntaria Aboriginal Ladies’ Choir from Hermannsburg, Central Australia. The denial of a vibrant and significant musical history in white as well as Indigenous culture has done this country a great disservice.

It may well be the prime reason why none of the 20th century’s great musical forms ever originated in Australia. Bebop, western swing, cajun, tango and samba (to name but a few) originated in lands also saddled with a colonial history. A tiny country like Jamaica has given birth to no less than calypso, ska and reggae.

To many, living in our current cut-and-paste paradise, this probably seems irrelevant and an irritation—why bother with the detailed sonic interconnectivity of the past when you can avoid both past and present by logging into, say, Second Life on the internet? I didn’t add “future” to the list of avoidance because you can guarantee that the future will be mostly a rehash of the past. It’s what we already have in Australia—everything from faithful copies of powdered wig Baroque to yet more hip-hop, to concerts where almost any plink or plonk from the 20th century is attributed to John Cage.

Unless we investigate and value our own extraordinary musical culture, the dreaded cultural cringe will continue to define what constitutes the practice of music on this continent.

interactions

So, first to History. It didn’t start off so badly. As Inga Clendinnen recalls in her book Dancing with Strangers, the firsthand account of Lieutenant William Bradley states that “the people mixed with ours and all hands danced together.” Musical gestures of friendship also took place. “The British started to sing.” The Aboriginal women in their bark canoes “either sung one of their songs, or imitated the sailors, in which they succeeded beyond expectation.” Some tunes whistled or sung by the British became favourite items with the expanding Indigenous repertoire of borrowed songs. Right there at the start we have a cultural give-and-take from both sides.

There is a unique recording made in 1899 of Tasmanian Aboriginal Fanny Cochrane singing into an Edison phonograph machine. The photo is stunning too, but that is all there is until anthropologust AP Elkin’s first recording in 1949 (as far as I can ascertain). Audio recordings thereafter document almost exclusively the music practice in Arnhem Land.

The recording of Fanny Cochrane is arguably one of the most important 19th century musical artefacts from anywhere in the world—certainly more important than the recording of Brahms playing his piano in the same year. With Johannes we still have the notation; without Fanny’s voice there would be nothing. And maybe that’s what we have wanted: ‘nothing’ to connect us to the horrors of Tasmanian history.

Translations of Central Australian Aboriginal songs were undertaken by Ted Strehlow in the 1930s, but he had his own Lutheran agenda and concentrated on ceremonial songs not personal everyday songs. He also wasn’t interested in how the songs actually sounded, the sonic structures, the grain of the music.

music for conquest & survival

“An impossible past superimposed on an unlikely present suggesting an improbable future.” Here Wayne Grady, in his book The Bone Museum, is describing the nature of the palaeontologic record, but he could be describing the culture of the modern Australian state. I find it a useful key. Let’s unlock some other musical history that has been documented.

We know that the first piano arrived onboard the Sirius with the first fleet. It was owned by the surgeon George Wogan. What happened to it is not known, but we do know that the import of pianos by the beginning of the 20th century had grown from a nervous trickle to a surging flood. The famous statement by Oscar Commetent that Australians had already imported 700,000 pianos by 1888 may be unsubstantiated, but the notion of one piano for every three or four Australians by the beginning of the 20th century could well be close to the mark.

A read through John Whiteoak’s groundbreaking book Playing Ad Lib presents a strong tradition of orality; and through observations of colonial Vaudeville, the music hall, the silent cinema, circus and theatrical events, he exposes a lexicon of unorthodox music-making more akin to the 1960s avant-garde and beyond than repressed Victorian society. If you like: the colonial 19th century was a period of fecund instrumental technique—music-making without the instruction manual.

Unfortunately, from the Gold Rush onwards, the common purpose of the colonisers became clear. Even the most enlightened were engaged in the wholesale destruction of Aboriginal culture, a political-economic agenda formulated by the powerful and still entering the law books via the mining industry to this day.

Even where Christianity worked a more moralistic trail of destruction compared to the pastoralists, the practice of music was both the medium of conquest and the medium of survival. Whatever your view of history, when the Hermannsburg Aboriginal Women’s Choir sing the Chorales of JS Bach in their own Arrernte language, with their own articulation, gliding portamento and timbre, it is an extraordinary and unique music that is being made. Started by Lutheran Pastors Kemp and Schwartz in 1887, the choir’s music is full of colonial cultural contradiction, but that music has also nurtured the Indigenous population through times of persecution and extreme physical hardship. The choir has gone from a 40-plus membership in its heyday of the 1930s to the current situation where it is difficult to muster eight singers—on our way to record the choir two years ago, two of the choir’s ladies had died in that week. This music could vanish in five years.

Mixed up with government policy to liquidate Aboriginal culture by placing mixed-blood children in institutions, in 1935 Aboriginal children with leprosy were “rounded up” (to quote the local newspaper) and placed in the Derby Leprosarium in Western Australia. An unexpected outcome of this brutal herding was the founding of The Bungarun Orchestra. To keep their fingers exercised, up to 50 patients performed Handel, Beethoven, and Wagner by ear—copying one of the sisters at the piano. And, according to their own testimony, the music helped the inmates escape the loss of their families and traditional cultural life, and also the painful injections of chaulmoogra oil [an ancient Asian cure from the seeds of the tree of the same name] into their bodies. Documentation of the orchestra shows dozens of violinists, the odd guitar, a didjeridu and some four banjo players. I’m not a fan of Wagner, but I would pay big bickies to hear a recording of Wagner with banjos. Unfortunately, the only audio documentation seems to be the singing of an Anglo hymn; nothing from the classical canon.

It’s a shocking frontier story, but my point is that the practice of music fulfilled a vital if contradictory role—it was part patronising western hegemony, and part genuine release, expression and consolation for those suffering.

lost tradition

Gumleaf playing may well go back thousands of years; again, the record is hazy. According to musicologist Robyn Ryan, it was documented first by pastoralists in 1877 in the channel country of Western Queensland. The gumleaf was used by Aborigines in Christian church services by the beginning of the 20th century, and reached popularity in the 1930s when the desperately unemployed formed 20-piece Aboriginal gumleaf bands at Wallaga Lake, Burnt Bridge and Lake Tyers, and armed with a big kangaroo skin bass drum, marched up and down the eastern seaboard—demonstrating defiance in the face of the whitefella and his economic methodology. The spirit of this music was not to appear again before the 1970s Aboriginal cultural revival. Alas, the band music itself has disappeared.

What has happened to this tradition? The Wallanga Lake Band played for the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932. Why isn’t there a 20-piece gumleaf band marching down George street on Australia Day? This is the New Orleans trad jazz of Australia. Who is looking after this, who is nurturing this?

My point is that you can and should research and write your own history—if it has content, it will ring true. It might also provide the materials with which to challenge the future.

an unmusical culture

There are good models of environmental performance in our recent past, but these are fairly isolated events when you consider that all music was an outdoor affair up until 1788. These aren’t quite up there with the Aboriginal notion of ‘If I don’t sing the land into existence, it doesn’t exist’, but some have tried to come close. I’m thinking of examples like The Gwotamala happenings organised by George Gittoes in the Royal National Park in the late 1970s; The Maritime Rites of Alvin Curran performed in Sydney Harbour in 1992; the Totally Huge Festival on a West Australian sheep station in 2001; the 2008 NOWnow festival in the Blue Mountains will go outdoors; the spectacularly successful Garma Festival in North-eastern Arnhem Land.

Here’s what Galarrwuy Yunupingu says about the Garma festival: “it’s about learning from each other the unique Indigenous culture as well as the contemporary knowledge that we learn from the white man’s world. This is about uniting people together and the weighing and balancing of their knowledge.”

How can we weigh and balance knowledge of music when only 23% of Australians get any kind of specialist music instruction in our public schools? It’s not just that the standard of what there is teeters from the bad to the abysmal; it’s the fact that music is just not rated as a necessary life skill, not rated in the same way that the notion of music as a profession has become laughable. Vast sums of money can be spent on the bricks and mortar of opera houses and conservatoriums, but noone wants to pay the musicians. The punters might pay for celebrities, but they resent paying for the real cost of live musicians, and by that, we know what the value of music really is in our society. Rock bottom.

Here’s some statistics taken in 2004 from the Music in Australia Knowledge Base [http://mcakb.wordpress.com]. Out of a population of over 20.1 million people, only 230,800 persons said they were involved as live performers of music. That’s a lot less than the number of pianos in Australia in 1888 when the population was well under 3 million.

So how unmusical have we become? That figure 230,000 includes unpaid and paid hobbyists as well as professionals. That’s 1.47% of the population. Out of that 1.47%, only 15.2% worked 10 hours or more per week. This means that less than 3,500 musicians were employed anything like full time in this country during the Howard boom year of 2004.

What was their worth? There are no figures, but of that initial boast of 230,800 people who said they had been involved in music somehow, only 11,500 said they received more than $5,000 dollars in that year. And that number would be seriously warped by the millions handed out to opera and the five orchestras. I disagree with the pronouncement from an ABC presenter who thinks that classical music needs defending —classical music does not need defending. Classical music has a hotline direct to the power elite of this country and has nearly the whole of the available subsidized cake and eats it too.

reciprocity & the future

For a musical praxis in the future to have any hope it must involve a high level of reciprocity—the ability to socially combine on a local and global level. It would have to be a catalyst that makes us more human. This has dangers—at its worst music helps us wage war more effectively; at best it brings us into communion with other selves—other species—the natural world from whence we came.

As Aboriginal models can teach us, music should be part of a continuum of creative practice involving sound, stories, and image—something integrated and interchangeable with geographical location; something that draws on all media, and we are now aware of that concept through the Internet.

We might be able to move from a position of musical impotence to one of strength if we choose to listen to the past. We whitefellas are in a unique position to learn from the Indigenous peoples of Australia. That doesn’t mean Nimbin hippy-style delusions of back to the bush; I’m proposing a society where there is, if not universal musical suffrage as was the norm in traditional societies, at least a situation where if you want to share knowledge, as when a Warlpiri woman tells a sand story, the most natural thing is to paint and sing this knowledge into existence. Technology can be used well to promote such notions, but it cannot replace original content, social connection, environmental context, and the wonder of firsthand experience, any more than we can replace the earth on which homo sapiens has become an uncontrollable parasite.

A few years ago Germaine Greer, in her essay White Fella Jump Up, proposed that Australia’s salvation might lie in becoming an Aboriginal Republic—an idea for which buckets of manure were poured over her head by the usual commentators. Well, I’d back almost anything that got rid of the British hereditary ruling class and that ridiculous Australian flag. However, the rub of the issue is this: our current models of music have not and are not serving us well. Instead of importing the latest theoretical cultural package from the USA or the UK, perhaps there are many elements in our Indigenous and colonial history that contain empirical guidance for the future of music as practiced in this country.

Mutawintji Aboriginal guide Gerald Quale once told me, “You whitefellas got the three Rs; well, blackfellas got the three Ls—look, listen and learn.” This strikes me as a good approach to our history and a methodology for the future if we want there to be music making of any value, but we are going to have to believe first that it is worth trying.

New Music Network, 2007 Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address: Listening to history presented by Jon Rose, The Mint, Sydney, Dec 3, 2007

Reproduced with the permission of the author and the New Music Network. The full address can be read at www.newmusicnetwork.com.au See also www.jonroseweb.com.

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 46