Living the RealTime life

I started working at RealTime in my twenties from 1998 to 2002, fresh out of university and a background steeped in cultural studies, film production and poststructural theory. I was a closet writer, drawn to arts and publishing, but uncertain in those first steps you take into a possible career. I was also new to Sydney, having abandoned Melbourne then Queensland where the recession meant no jobs for graduates in media or communications. When it came to the arts, I was more mainstream than Keith and Virginia might have imagined, but with a sense of the obscure and abstract ignited by a major in cinema theory at RMIT with Adrian Miles and Mike Walsh, who went on to write regularly for RealTime.

In the interview for the assistant editor position, they asked me if I liked opera. I said I liked everything. This was pretty much true and hasn’t changed: I’m open to the elements. To apply for the job, they asked for examples of my writing. I sent miserable poetry, a couple of early short story drafts I’d never shown to anyone else and an essay about Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil. Or perhaps it was David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. I remember Keith’s response clearly: “You were chosen on the potential of your fiction.” It struck a chord and inspired me to action in terms of my essay skills. Keith and Virginia commissioned me to write 1500 words per edition for four years. One hundred articles later, it was the best education in the Australian arts scene, arts writing and editing I could have imagined.

I put my hand up for any free ticket. I saw dance, performance art, digital media, sound installations, documentary festivals. I was often afraid and bewildered as an audience member — the only person in the room who didn’t get it. I initially preferred the boundaries of stage and performer (gasp!). But I learnt to love crossing this line and many others. A highlight was attending the 2000 Adelaide Festival as a roving arts commentator, responding daily and on the go to produce mini-editions; I loved the thrill and risk and the intense immersion — and how the writing seemed to stand up to the task. It was in the process of subediting each edition of RealTime that I came to understand how to get it. It was a massive job putting an issue together: intellectually rigorous, stimulating, finding depth in the new.

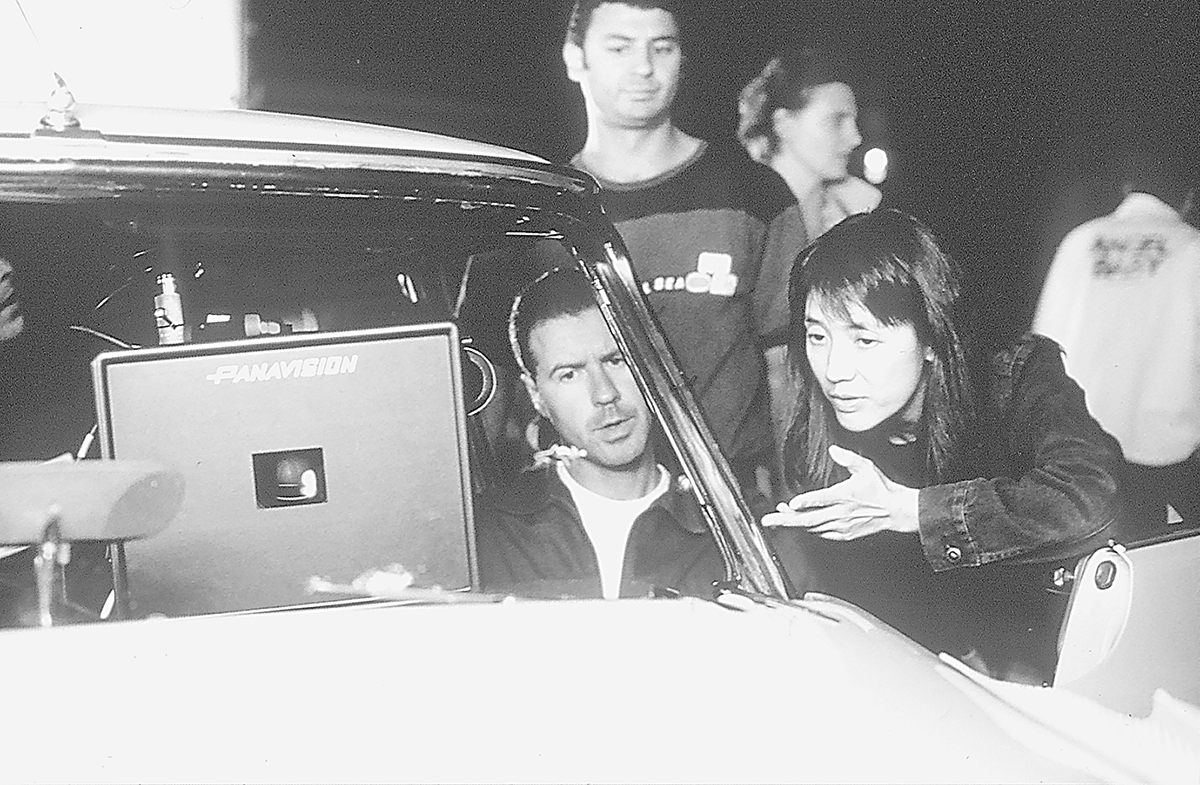

Clara Law directs The Goddess of 1967, 2001

A number of artists stay with me years later: Lucy Guerin, Les Ballets C de la B, Justine Cooper, Kate Champion, Ross Gibson, Legs on the Wall, Martine Corompt, Ivan Sen, Not Yet It’s Difficult, Cate Shortland, Clara Law. And a number of writers too, those who I always put on the bottom of the pile to be read, a reward at the end of the day: Phil Brophy, Erin Brannigan, Simon Enticknap, Melinda Rackham, Mike Walsh, Mireille Juchau, Bec Dean, Daniel Palmer, Josephine Wilson and Adrian Miles (a sad farewell, Adrian). But I can’t actually guarantee that I saw the above artists’ work IRL. Sometimes the writing by RealTime writers was so evocative I now remember it as if I was really there.

Looking back on my fledgling articles, I see all the mistakes of a beginning writer: the need to impress, the need to obscure, the need to show off style for no apparent reason, the need to endlessly repeat words to go on the rhythmic road with Kerouac and Burroughs, the redundancies (that was a new word I heard often, ouch!) and the tendency to use the form of wit as cruelty — something I’d never do now. Much of it was obfuscation but as the articles progressed, I began to experiment and found I was in the right place to test things out. I liked how the real time idea infused the writing, the sense of experiencing the show as keen as the show itself. It was an exciting discovery, fictocriticism, and one I have enjoyed since. I recently followed Laurie Anderson around HOTA (Home of the Arts) on the Gold Coast for a week and as soon as I arrived I felt this kind of RealTime-comfort-zone, the space of the lyrical essay laid out before me.

A couple of years into my life at RealTime, I became Editor of OnScreen, the film and digital media section. Film remained my passion. At the media screenings — sitting next to David Stratton towards the centre with his umbrella perched on a seat or Margaret Pomeranz laughing in the front row — the reviewers were given champagne and snacks in penthouse suites. After a good film all the reviewers were silent in the lift down. I couldn’t really believe I got paid for such pleasure. But with all the genre-bending and boundary-pushing going on around me, I found it hard to return to traditional forms. When Keith asked me to write editorials for OnScreen, I’d spend months trying to work out how to subvert this idea: an editoral about why no-one reads editorials?

There was a great sense of possibility in film culture at the time, especially in shorts, documentaries and Indigenous filmmaking or films about Indigenous stories. Ivan Sen, Rachel Perkins, Beck Cole, Warwick Thornton, Catriona McKenzie and Darlene Johnson were starting to make evocative films. Highlights for me were Ivan Sen and Cate Shortland experimenting with form and narrative style in shorts (Sen’s Tears, Dust and Wind; Shortland’s Pentuphouse, Flower Girl), before going on to make features, while in documentary Dennis O’Rourke’s Cunnamulla was bringing similar themes to the surface in his exploration of teen girls in a small country town and their (lack of) options. I received only two pieces of fanmail working at RealTime and both were about this article: Mark Mordue wrote to encourage me re style; O’Rourke wrote to thank me for getting it:

“The annual lizard race features on the Country Link brochure. ‘The most boring entertainment I’ve ever witnessed,’ according to Neredah, who’s seen a lot; she observes for a living. Local contestants are rounded up and placed in a large circle. First to the line wins. No worries, this’ll be a quickie, but what happens? Overcome by collective inertia, they will not, cannot, move. A man stomps. Nothing. Is it lethargy, fear or an attempt to fit in that’s holding them back? Cara and Kellie-Anne know the answers but they’re in a bus heading to the big smoke…”

Shelley Jackson, Patchwork Girl

My years at RealTime, both in day to day work and content, were mostly about the slow dawn of the digital, the melding of text and screen. It felt like everything was new but looking back it was ponderous. I did the RealTime website using only HTML coding which took days and days, I didn’t have a mobile, there was no social media, and all the images in the paper — “must be from the performance, not publicity shots“ — were beautiful black and white photographs, sent by publicists or artists between flat bits of cardboard that I scanned and posted back. I thought CD-Roms were going to revolutionise storytelling. I became interested in the intersections formerly known as hypertext and wrote a regular column called Write Sites, as far as I know the only one in Australia devoted to this genre. I interviewed Eva Gold about the world-first inclusion of hypertext Patchwork Girl in high school curriculum.

“Patchwork Girl looks at the act of writing as much as text itself, ‘tiny black letters blurred into stitches,’ as a creation process not full of Mastery; this is a woman making a monster, this is Mary/Shelley. The metaphors of quilting and patchwork have been consistently used for hypertext writing (eg TrAce’s Noon Quilt project), sewing together nodes, acknowledging the process as much as the outcome, its made-ness.”

Many digital media artists covered, like Mez and Jason Nelson, went on to become internationally renowned practitioners. But it wasn’t a genre that captured much attention in Australia. Looking back, there was a stiltedness to the text, the visuals and process, the merging of the fields, as compared with video games, covered by the brilliant Alex Hutchinson:

“An important thing to remember is that video games were born on, and exist only on, computers. Unlike pure text, they are the rightful heirs of the digital age, not its bastard children. The ‘links’ between text fragments become the doorways between rooms rendered in 3D. The text ceases to describe or refer to the image, and begins interacting with it, fleshing it out, giving it greater depth. Your average game player becomes blind to the fact that s/he is making choices between fragments, and their reinterpretation of the game becomes fluid. S/he ceases to be an external force acting on the text and becomes another facet of it.”

In terms of my own writing experiments it was hard to know when to stop. To their credit (arguable) and my surprise, Virginia and Keith often went with it. One of my strangest memories is of writing about digital porn (gasp!) under the avatar Ivana Caprice with her husband Art, new to the internet. I have no idea why. I thought this was the most hilarious thing I’d ever written until I watched the faces of the proofreaders when they came to this article. They didn’t smile. Once. They just didn’t get it.

“Art tries to download Jessica’s shoot right to our computer. Here’s Amy, ‘wild crazy…watch her lean back and piss into a glass bowl.’ Look at the quality of that scan, Art cries, zooming into a pierced nipple. They use digital cameras, the site says proudly, giving a quick plug to the Sony VX 1000. See pissing, fisting, bottle and veggie insertions, and a speculum … I have to certify that ‘anal sex, urination, vegetable and bottle penetration and fisting, do not violate the community standards of [my] street, village, city, town, country, state, province or country.’ I am nervous about this …Aaaah, ooooooooh, 2 girls are engaged in a lip pulling contest and then there’s the carrots. Eggplants. Zucchinis. Squash. Art reckons this site’s so hot he’s going to cook a stir fry tonight.”

With a small team (Keith, Virginia, Gail Priest and I), RealTime felt like family for many years. Passionate, hard-working and unconventional, Keith and Virginia had a strong sense of vision and support for innovative artists and writers. And it was a publication I leant on heavily even as I stopped working there. If I had an unusual idea about a new TV show or a regional artist/event to cover they were always keen. Sometimes, years later, when I’d take the train in from Castlemaine and pick up the paper at a café in Melbourne, I’d think ‘who are all these artists?’ Many amazing practitioners flying under the radar except for Realtime. It now feels like there’s a large gaping hole.

But one thing Keith and Virginia were always good at was archiving. I spent a lot of time setting up FileMaker databases and entering data. Being able to see all this content online now, at least in terms of my earlier writing, has been a wistful, revealing and sometimes excruciating experience. But more wonderful has been the chance to revisit the RealTime writers and artists we nurtured along the way, many still thankfully going strong 25 years later.

–

Kirsten Krauth is a writer and editor based in Castlemaine. Her first novel just_a_girl was published in 2013 and her second in progress is based around the twilight worlds of the early 80s Melbourne music scene. She is editor of Newswrite for Writing NSW and her writing has appeared in The Saturday Paper, ABC Arts, Good Weekend, The Australian, SMH/Age, Island, Australian Author and Empire.

Top image credit: Cunnamulla