loungeroom critique

joni taylor on linda wallace’s back to berlin

Linda Wallace, LivingTomorrow (2005)

THE GALLERY NEWYORKRIOTOKYO IS A TYPICAL INDEPENDENT ‘PROJECT’ SPACE IN BERLIN, DIRECTLY ACROSS FROM THE FORMER NO MAN’S LAND THAT SEPARATED EAST FROM WEST. BUT FOR THE EXHIBITION BACK TO BERLIN, AUSTRALIAN-BORN ARTIST AND CURATOR LINDA WALLACE TRANSFORMED IT INTO A SUBURBAN LIVING ROOM THAT OFFERED UP A CHALLENGING THREE-CHANNEL VIDEO TAKING ON MULTICULTURALISM, MEDIA AND MURDER AS THE EVENING’S ENTERTAINMENT.

Back to Berlin also presented earlier works, entanglements (2004), first shown at the Adelaide Biennial, and LivingTomorrow (2005) alongside a new work, TOR (2006), and a selection of silk prints of video stills. The show’s title refers to the fact that the Amsterdam-based Wallace lived in Berlin for a year recently, and that her mother’s family can be traced there from around 1650 to 1850.

Wallace works as a video artist utilising diverging, interweaving narratives created from found and self-made media-text, images and sound—all reworked and combined to reveal weighted meanings within the new structures.

In her earlier works Wallace played with digital and analogue textures. Lovehotel (2000) combined the cyberfeminist poetry of Francesca da Rimini with Wallace’s own video, and in eurovision (2001) reworked film and TV footage were displayed on various interfaces. Framing devices also made reference to emerging online environments of the web and the interplay of concurrent storylines.

LivingTomorrow goes one step further into narrative complexity. Here, the way the source material is viewed over the three screens is determined by a database, designed by Wallace while artist-in-residence at Montevideo in Amsterdam. While the Berlin version was exhibited as a three-channel DVD, the original was exhibited running from an archive of video clips and subtitles sent by the database to the screens and potentially in any order. The ‘story’ had to be written to accommodate randomness and still make sense to a viewer.

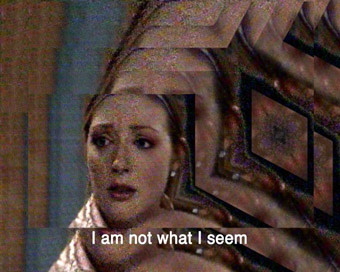

In Berlin, LivingTomorrow was viewed from the comfort of a well-worn couch, the white cube rejected for the wohnzimmer. It’s the familiar TV experience, whether located in former East Berlin or southeast Queensland, a universal ritual or, as Wallace says, “our window on the world.” The way the work is installed also gives permission to spend time with it, allowing the visual medley to wash over the viewer in an almost hallucinatory way. But if video art is the bastard child of TV, this work would have to be the mongrel half sister. Images of soap opera, wars, headscarves and the Dutch countryside merge with disjointed and repetitive subtitling to form unnerving storylines. While definitely a televisual experience, the images on the triptych of screens are digitally manipulated, creating an eerie reflection of the already mediated media image.

It’s a cut-up screen, the blonde American idols slashed and deformed, their overbearing silences and stares emphasised to the point of extremity, their repetition driving home the sheer banality of the confined spaces and studio sets so much a part of daytime soap opera. The Bold and the Beautiful is reputably the most popular TV series in the world, viewed by over 450 million people a day. Wallace herself became interested in the show while in hospital during the birth of her son.

But like a fractured mirror or a kaleidoscope, other images appear—a woman with a headscarf, machines of surveillance, a technology park and a corporate logo: “Living Tomorrow—Where Visions Meet.” Occasionally there are glimpses of beautiful naturescapes. The Dutch countryside of fields and open blue skies offers a wake up call to those locked in claustrophobic interiors.

Subtitles appear randomly, suggesting further narratives. Wallace has combined her own scripts with extracts from “The Coming Wars” in the New Yorker, “New Breed of Islamic Warrior is Emerging” in the Wall Street Journal, and Osama Bin Laden’s 2004 speech.

Linda Wallace, LivingTomorrow, detail (2005)

The subtitles written by Wallace herself carry the main ‘storylines.’ They involve a girl wanting to wear the headscarf, various murders and refusals of marriage. None is from The Bold and the Beautiful, but by their nature we are lead to trust their authority.

While The Bold and the Beautiful is glaringly distant from European life and a changing world, Wallace, with her foreigner perspective, creates a palpable reality, tackling a multinational Europe and conflict based on religious beliefs. Her images have a damaged tangibility: the transmissions of the soap opera were disrupted by a series of electrical storms which interfered with the reception. So although resembling analogue decay, the images were partly created by nature thus emphasising the materiality of the medium of television. Wallace describes the effect as “the weather hacking into the work”.

And this is not the only ‘reality’ injected into Wallace’s artmaking. While she was working on the project, the vehemently anti-Muslim Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh was assassinated near her home in Amsterdam. The realities of ethnic and religious conflict were literally brought to her doorstep. The initially abstract narrative for Living Tomorrow grew to include this event, yielding a visceral sense of place, abstracted in the soap, abstracted in nature, but rooted in the real.

The work’s landscape images also speak of place, and the difference between Dutch countryside of planned agricultural development versus the Australian bush. An Albert Namatjira print framed by curtains also hangs on the wall of the gallery. For Wallace, this print speaks primarily to Aboriginal Australia but is also reminiscent of the photographs of the outback in the Women’s Weekly she grew up with, a reminder of the bucolic and provincial nature of a ‘wild’ Australia but from a sanitised viewpoint.

Also hanging on the walls are silk prints of video stills from the works. One series is from LivingTomorrow. Another of a dead female Chechen militant, lying in the theatre seats after the tragic Moscow Theatre Siege of 2002, is from the work, entanglements, a montage of Australian news footage relating to war in the Middle East—the living room idyll shattered by actual political consequences.

In a corner is a short work called TOR (meaning goal), shot on the evening that Germany beat Argentina in the 2006 World Cup. Wallace’s take is once more a strangely multilayered grappling with what nationalism and identity mean today in a mixed Europe.

In TOR, German fans of all races, dressed in the yellow, red and black team colours, are euphoric with what can only be described as out-of-control, sports mania. They scream into Wallace’s camera, dance in the streets, harass drivers. A mother in camouflage pants dances wildly around her parked car while her children sit, bored, on the car roof. The spirit is of spectacle, but in Wallace’s showing it’s also silent. In a country where cultures clash, they are connected by the recognisable ensignia of a team, united by a tradition and rites different from their own.

The overlapping images and text in Back to Berlin allow the audience to walk in at any time and bear witness to the myriad meanings present in the global televisual world. LivingTomorrow is constantly generating something new, the story lines merging to create new realities and reflections on a world in flux.

Linda Wallace, Back to Berlin, NewYorkRioTokyo Gallery, Berlin, Jan 1-Feb 11; http://machinehunger.com.au

RealTime issue #78 April-May 2007 pg. 29