making images with audiences

scott mcquire: rafael lozano-hemmer, adelaide film festival

Pulse Room (2006), Mexico, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

photo Antimodular Research

Pulse Room (2006), Mexico, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

IN MARCH, RAFAEL LOZANO-HEMMER WILL BE ONE OF THE KEYNOTE SPEAKERS AT THE 2009 ADELAIDE FILM FESTIVAL. WHILE NOT A FILMMAKER IN ANY TRADITIONAL SENSE, LOZANO-HEMMER’S ART PRACTICE, WITH ITS INNOVATIVE USE OF LIGHT AND PROJECTION, IS HIGHLY RELEVANT TO THINKING ABOUT CINEMA IN A CONTEXT WHERE OLD DISTINCTIONS—BETWEEN FILM, PHOTOGRAPHY AND VIDEO AS SPECIFIC MEDIA, BUT ALSO BETWEEN CINEMA AND ART AS ZONES OF PRACTICE—HAVE ERODED.

Although he has been exhibiting for over a decade and half, Lozano-Hemmer’s only work so far shown in Australia was Homographies at the Sydney Biennale in 2006. (Fortunately, he maintains an excellent website with an archive of works, including extensive still and video documentation.) This should change over the next year or two, with projects under discussion for Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide, as well as the acquisition by Tasmania’s MONA of the Pulse Room installation shown at the 2007 Venice Biennale.

One thing immediately evident in reviewing Lozano-Hemmer’s practice is his interest in working in series. This is signaled firstly in naming, notably the titling of his large-scale public projection works as “relational architecture” and his various gallery-based works as “subsculptures.” It is also manifested practically in the restaging of works in new locales and conceptually in the reconfiguration of elements of a work to explore a particular line of thought. Lozano-Hemmer notes: “Often I work parasitically: I scout a site, for instance, meet local eccentrics and stakeholders, and learn about its constraints and peculiarities. The project uses any of that information as a starting point for development. Other times I am interested in a phenomenon or an effect and pursue variations of that in different scales, or speeds or contexts.”

For instance, Vectorial Elevation (Mexico City, 1999-2000), Amodal Suspension (Tokyo, 2003) and Pulse Front (Toronto, 2006) all involved the utilisation of powerful searchlights in public space. Unlike the dominant modern aesthetic of centrally-controlled urban light spectacles, exemplified by Albert Speer’s notorious “light dome”, Lozano-Hemmer designed forms of public access, making operational the Lettrist proposal that “All street-lamps should be equipped with switches; lighting should be for public use.” While all three projects are united by the aim of redistributing social agency in public space, each deployed a different interface. In Vectorial Elevation, the lights were manouevered via an internet webpage which also became an open platform for comment; in Amodal Suspension the protocol centred on the mobile phone and SMS; while Pulse Front utilised a network of sensors to align the rhythm and orientation of 20 searchlights around the Toronto harbour with the pulses of passers-by.

Series also overlap. The sculptural interface for Pulse Front was similar to that initially developed for Pulse Room (2006), and the biometric principal has also informed recent works such as Pulse Tank (New Orleans Biennale, 2008) and Pulse Park (Madison Square Park, New York, 2008). Lozano-Hemmer comments: “I have done so many pieces with a pulse interface that I have been criticised for ‘recycling’ the interface and not truly innovating; my feeling about this is that it is an experimental approach where you must undertake these variations to get closer to developing a language or typology of interaction. Until a particular combination of media is in concert one does not really know how effective it will be.”

Interest in exploring the typology of interactions is also evident in his subsculpture series, which often involve the movement of massed identical objects. Homographies consisted of 144 fluorescent lights arrayed in a conventional modernist grid. Distributed at ceiling level above the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ main entrance court, the lights were mounted on moveable fixtures controlled by computerized surveillance systems. Seven cameras tracked the movement of visitors, triggering the rotation of the individual light tubes. A series of plasma screens along one wall showed visitors seen from the perspective of the tracking system overlaid with positional data. Wavefunction, which was first staged in Venice during 2007, consisted of nine rows of four chairs arrayed in a grid. The chairs, which combined the classic Eames plastic seat with the famous Saarinen base, filled most of a small rectangular room. As the audience entered the room and walked around, the chairs responded to their presence by moving up and down their vertical axes, generating complex ‘waves.’

Automated movement of objects often generates a strong sense of the uncanny. With works like Homographies and Wavefunction, surprise at the fact of movement is quickly overtaken by interest in the nature of the movement. It is not the position of any one object that is significant, but the movement of the set. What is being actively defined in the interplay between observer and set of objects is a field of relations. If the science of non-linear causality can be understood as the attempt to reconceptualise apparently random phenomena, this undertaking has been paralleled by the increasing importance that contingency and chance has assumed in modern and contemporary art. For Lozano-Hemmer digital media raise new possibilities of “programming without teleology.”

It is the uncertain nature of this encounter between the human and the technological which continually animates Lozano-Hemmer’s art. It also propels him into new forms of collaboration with both peers and audiences: “I programmed enough to know that I am a lousy programmer and thus I work with people who are very specialized…My model is similar to the performing arts: I am the director but there is also a composer, a programmer, a designer, a photographer or whatever other specialisations are required by the piece. In the end, though, there is a definite bias or idiosyncrasy that must be followed in order to ensure that the project has consistency.”

Under Scan (2008), London, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

photo Antimodular Research

Under Scan (2008), London, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

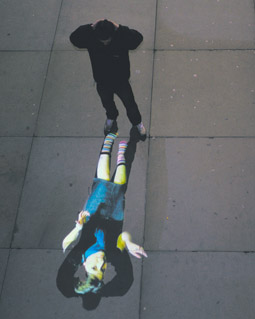

His large-scale public space works such as Body Movies and Under Scan demonstrate the potential for counter-intuitive uses of surveillance technology such as motion tracking systems to generate novel and creative forms of affective sociality. Body Movies involved the projection of a database of large-scale portraits onto the façade of a cinema in a public square. However, the portraits were rendered invisible due to powerful xenon lights directed on them at ground level. It was only when pedestrians walked through the square and interrupted the light that the projected portraits were ‘revealed’ in the silhouettes of their shadows. Similarly, Under Scan involved thousands of ‘video portraits’ projected onto the ground in central city thoroughfares and public spaces. The portraits appeared intermittently in the shadows cast by pedestrians, their absent subjects turning and then looking away as the passer-by left the scene. Both works used sophisticated ‘real time’ monitoring of pedestrian movement: in Body Movies, to switch to another set of images whenever all the portraits in a given scene were revealed, in Under Scan to ‘place’ portraits in a pedestrian’s predicted path. This design shifted the nature of ‘interactivity’ from its common reduction to choice from a menu of relatively predictable consequences to a far more open horizon in which contingency and unpredictability assumed a greater role. Instead of the logic of ‘taking turns’, where single users control the apparatus and produce representations that others watch, multiple users could simultaneously explore a multitude of different pathways.

These projects are not just about watching images, but depend upon the co-presence of the crowd— on interaction with others—in order for things to happen. Lozano-Hemmer stresses the active role of the public in ‘completing’ these works: “That’s a collaboration that has often been identified (for example in Duchamp’s maxim “le regard fait le tableau”) but now it is inherent to any interactive proposal. In the end Body Movies or Vectorial Elevation are platforms that are taken over by the public…If no one participates the pieces simply do not exist.”

Lozano-Hemmer’s platforms are notable in achieving a deft balance between individual agency and collective interaction, between active engagement and reflective contemplation. While technically sophisticated, they promote modes of interaction that are not simply instrumental. Passersby aren’t initially sure what is going on, but can best learn by joining in. Habit is suspended in favour of experimentation. When Under Scan was staged in London last November, Lozano-Hemmer found the location improved this experimental aspect: “The project in Trafalgar Square benefited greatly from the fact that there is already a lot of foot traffic at night. This meant people would just ‘encounter’ the work as they went home after work, for instance, rather than having to go to a specific site to see it.”

Despite their scale, the aim of these works is to initiate playful encounters rather than sublime experiences. Lozano-Hemmer observes that Under Scan “is quite underwhelming if your expectations are to see a grand cathartic spectacle in the tradition of son et lumiere or fireworks shows. Yes, we did use the world’s brightest projectors and covered 2,000 square metres with interactive portraiture, but the goal was in fact to create a situation of intimacy not intimidation. Technologies which are used for advertising, or Olympics or rock concerts are here transformed to deliver discrete, individual experiences with no proscenium, no preprogrammed narrative, no privileged vantage point.”

Intimacy is also a hallmark of the recent ‘pulse’ works such as Pulse Room which featured at the last Venice Biennale. The work consists of a grid of 100 incandescent light bulbs suspended in a room. The rhythm and intensity of each discrete light varies in response to the pulse of visitors measured when they grasp a sensor. As new users contribute data, the traces of past visitors move to the next position along the grid. Eventually, the room is filled with a complex pattern made from the mixing of 100 different heartbeats. It is a breathtakingly beautiful work which offers a profound image of the weaving of individuals into a collective without the loss of their uniqueness: an image of multitude rather than mass.

Adelaide Film Festival and Samstag Museum of Art, Art & Moving Image Symposium, Feb 27, 6pm, keynote address Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

RealTime issue #89 Feb-March 2009 pg. 22