Michael McMahon: Seeing is believing

Dan Edwards

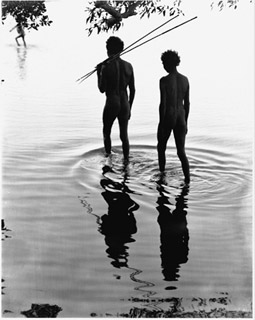

Nellie and Bambi Stewart, Thomson of Arnhem Land, 2000

DF Thomson, Courtesy of Mrs DM Thomson and Museum Victoria

Nellie and Bambi Stewart, Thomson of Arnhem Land, 2000

As a former lawyer with a passionate commitment to social justice, it is appropriate that producer Michael McMahon has focused on documentary film. The search for the kernel of truth at the heart of any story is what first drew him to the form. Since forming Big and Little Films with director Tony Ayres ( Walking on Water, 2002) 4 years ago, he has produced an impressive array of award-winning works, with Thomson of Arnhem Land (director John Moore, 2000) and Wildness (director Scott Millwood, 2003, RT60, p17) both earning AFI Awards. If there is a common element in the films McMahon has produced, it is their concern with people forced to fight for what they believe in.

How did you first come to producing?

In the 1980s I had a law practice and a lot of friends who were involved in the arts. I wasn’t going to have a stellar career as a lawyer so I thought I should find something I could do with a lot more passion. So in 1988 I produced a short film, Cruel Youth (1988). After that I went to work at the Arts Law Centre of Australia, focusing on the legal aspects of arts practice, and that has helped me enormously as I’ve moved more into producing over the last 6 or 7 years.

All your projects in recent times have been documentaries. Was this a conscious decision?

It was. After the success of Sadness [director Tony Ayres, 1999, based on William Yang’s stage performance of the same name] I was very keen to explore documentary as a form of story-telling with that core centre of truth. I enjoy the process of making documentaries and working with the writer and director to get to the crux of the story.

Your company profile states you are committed to creative partnerships between script writers, directors and yourself. How does this creative partnership play out in the actual making of a film?

I see my role as one of facilitation and support for the story-teller. Facilitation inasmuch as the writer/director has come up with the idea and as a producer I then have to facilitate the bringing of that story to the screen. That involves commenting on the script, getting whatever help is needed to improve the script, and facilitating the production in terms of finance. In our system it has to be attached to a market, so I have to think about the audience this documentary is going to appeal to. When that’s done and it’s time to actually make the film, I have to support the writer/director through that process: putting together a good crew and ensuring they work in a cohesive way, and then supporting the director through the actual shooting. Then there’s the post-production process, where I’ve always been happy to leave the editor and director in the edit suite until they’re ready to show me a rough cut.

Do you find yourself very involved in on-the-ground work during the actual shooting phase?

I think in documentary it’s often inevitable that as a producer you are pretty hands on. And I suppose that’s the role I’ve wanted to assume. I’ve been keen to learn and understand the process of making a documentary, and the only way I’ve been able to do that is actually be out there, on top of Mount Wellington in Hobart at 6:30am, trying to co-ordinate an aerial shot with cast and crew. You need to do that to know what everyone is going through.

On what basis have you selected the films you’ve produced?

To date with all the documentaries I’ve made I have been approached about being involved and I’ve made an assessment about the project. I guess I look for an intuitive personal response to the human story and the human journey that particular subject has undertaken. I think there’s always something about the core of the story that relates to my personal experience. And I have to be able to see that this story will work, educate and inform and possibly even change the views of audiences.

Have you felt the pressure to conform to what the broadcasters want in choosing your projects?

Yes. I think there has been a fundamental shift in documentary making in this country over the last 15 years or so to an almost absolute dictation by the broadcasters as to what gets made. That’s through the pre-sale system, which is really the only way you’re going to get a documentary made in this country. In the 80s documentary makers were able to make films and take them to the broadcasters. But that’s almost impossible now—we absolutely rely on pre-sales.

Have you had to knock back projects because you felt you wouldn’t be able to sell them to a broadcaster?

If it’s something I’ve felt really strongly about then generally I’ve taken it on, but not always with success. For example, there was a project called Pretending, which is about a gay man who was convicted of a murder here in Victoria about 5 years ago. It’s about the way the justice system deals with difference. I feel really passionate about that particular story, but we haven’t been able to get a pre-sale.

Would you agree with the prevalent view that a creeping conservatism at SBS and the ABC is limiting the potential for innovation in the documentary sector?

I think as a general statement yes, I would agree with that, but every now and then you get one under the radar. Last year I was executive producer on a documentary about 2 gay men [Man Made—The Story of Two Men and a Baby] who entered into a surrogacy arrangement through an agency in the United States and had a child who they brought back to Australia. It was pretty confronting subject matter, directed by Emma Crimmings in her first full-length documentary. I think the articles in the press and the publicity around the broadcast of that documentary did challenge the current prevailing notions of family. And I think SBS is absolutely to be applauded for supporting the making of a film like that. But I think overall there has been a much more conservative approach to documentary subject matter by both the public broadcasters in recent times.

What’s your perception of the current state of Australian documentaries in general?

I think generally film and television activity in this country is at a low and inevitably the documentary sector is part of that. But I think there’s a core of wonderful documentary makers. If that situation of the broadcasters dictating what gets made can be broken then I think we stand in a fantastic position to re-energise the sector. There is a core of wonderful people who constitute a very real and vibrant documentary sector but there is that fundamental problem of having so few opportunities outside the broadcasters to actually push the form, the way stories are told and the stories that actually get told. But we also have to remember that both our public broadcasters are now delivering documentary timeslots which are much better than we’ve had for quite a while.

Your company currently has some feature films in the pipeline. Are you wanting to move more in that direction?

Despite the success we’ve had with documentaries, as a company we’re probably moving away from the form. Just because of the difficulties in financing and the downward pressure on budgets. There are very few people in this country who can build a viable business on documentary production. So we have to diversify as a company, but that’s not to say we won’t keep doing documentaries.

Are things any better in the feature film market?

I don’t think they’re any easier, but I do think with the changes to the FFC guidelines at the moment the possibilities of financing feature films are expanding. We have 2 feature scripts in the market place: Semi-Detached and The Home Song Story. On the documentary front we’re polishing the draft of You Can’t Stop at Evil, the story of a South African-based New Zealand-born priest who had his hands blown off in a terrorist attack in 1990. Our other documentary is the Brenda Hean story, Death by Flying, which Scott Millwood is writing. We’re developing it as a feature documentary with the aim of theatrical distribution. It’s a logical step for Scott after Wildness.

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 15