mirror stories: the implicated audience

john bailey immersed in anna tregloan’s black

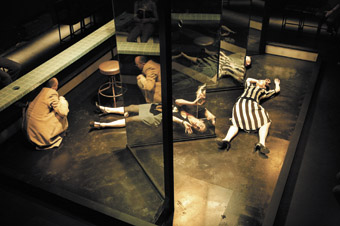

Black, from left James Wardlaw, Moira Finucane, Caroline Lee

photo Jeff Busby

Black, from left James Wardlaw, Moira Finucane, Caroline Lee

THE LITERARY CRITIC BRIAN MCHALE WAS THE FIRST TO SUGGEST THAT THE SHIFT IN A POETICS OF MODERNISM TO ONE OF POSTMODERNISM CAN BE TRACED TO PROBLEMS OF EPISTEMOLOGY SUPPLANTED BY THOSE OF ONTOLOGY. THAT IS, THE GREAT MODERNIST WORKS WERE ONES WHICH ASKED “HOW CAN WE BEST REPRESENT AND INTERPRET THE WORLD?” A POSTMODERN WORK, ON THE OTHER HAND, ASKS THE ANTERIOR QUESTION: “WHAT IS A WORLD?”

Concerned less with finding a more truthful, accurate form of expressing “all that is the case”, to appropriate Wittgenstein’s phrase, a postmodern work instead tremulously queries the very existence of a knowable, retrievable reality—or at least questions an art work’s ability to reproduce it. This seems to me the dominant characteristic of Anna Tregloan’s Black.

Tregloan’s performative installation takes as its ostensible subject the notorious 1947 “Black Dahlia” murder of Elizabeth Short in Los Angeles, establishing expectations of a kind of True Crime theatre of reconstructions, drawing on the many texts which have attempted to ‘solve’ the famously enigmatic killing and presenting something which attempts to make sense of the panoply of conflicting evidence. But of course, theatre cannot solve a murder, and Black turns out to be something very different indeed.

Tregloan is an inspired installation artist and set designer, and the piece is very much of the character of a living exhibition. The space is exquisitely designed: the audience navigates separate rooms, staircases, a balcony overlooking the main playing space—itself a beautifully crafted folding screen of glass panels which multiplies perspectives.

Four performers (Caroline Lee, Moira Finucane, Martyn Coutts and James Wardlaw) inhabit this central area, speaking snatches of text which sometimes coincide and are sometimes more opaque. As the viewer navigates the space, they are offered different sightlines on the unfolding drama, no one vantage point allowing a total perspective. And the glass panels, visited by a constantly changing lighting rig, magnificently reflect and refract the images of those passing by, at times dividing them but more often allowing them to occupy several spaces at once, ghostly images interacting with more corporeal presences.

Tregloan doesn’t make sense of the drama, at least on the level of narrative. Rather than offering a movement from mystery towards some kind of resolution, even on the psychological level, the performance is cyclical, roughly 40 minutes long, repeating without pause over three hours. Phrases recur, and thematic motifs (ice, salt and sugar) offer teasing but ultimately unedifying hints at an underlying structure inaccessible to the observer. The audience comes and goes, constructing their own beginning, middle and end dependent not on the assimilation of a pre-existing narrative structure but on the simple storyline traced by their roaming, their interest or boredom, tired feet or restlessness. The always partial perspective afforded by the spectator’s position is temporal as well as spatial.

All of this works to implicate the viewer on that ontological level. Though we may initially look to the piece for a solution to a classic mystery, we soon cannot help but realise the ways in which our own position as observer will necessarily not merely distort the truth, but construct it.

Similar ontological questions are evoked by GoD BE IN MY MouTH’s Grace, a spare performance both confounding and transcendent. It is deeply indebted to a surrealist or absurdist tradition but maintains enough of a linear narrative to leave audiences dissatisfied with the whole—or at least those audience members I spoke to afterwards, along with a swag of ambivalent reviews. The problem seems to me to be one of interpretation: it is entirely unclear what kind of ‘reality’ the piece presents, and therefore how we are to read its various competing elements.

There is a story, certainly, and characters, and a movement which echoes a traditional narrative structure. Long-separated and recently orphaned siblings Serbia and Wade arrive at the rooftop dwelling of their eccentric uncle, who lives with the half-human/half-pigeon experiments he has been working on since his disgraced departure from street-level existence. He holds the key to their inherited fortune, but is also embroiled in their puzzling past more profoundly than they realise. Though far from a naturalistic work, Grace still suggests enough realism to rouse those parts of the mind which look to establish a meaning behind a tale’s telling.

But there are aspects which actively work against such a reading—those overtly surreal moments—but also a seemingly deliberate attempt to stonewall interpretation, render uncertain any definite reading of the work. It is a theatre of moments, of dazzling soliloquies touching on mortality and redemption, and equally of inane pop dance routines enacted by ridiculously attired feather-heads. The final poser is not “what is really being said here?” but “is anything being said at all?” Which might well be the most challenging question a theatremaker can dare to ask.

Black, created by Anna Tregloan, performers Caroline Lee, Moira Finucane, Martyn Coutts, James Wardlaw, sets & costume design Anna Tregloan, composition & sound design David Franzke, lighting design Paul Jackson, dramaturg Maryanne Lynch; Tower Theatre, Malthouse, March 17-April 1; GoD BE IN MY MouTH, Grace, writer-director James Brennan, performers Katrina Miilosevic, Luke Mullins, Brian Lipson, Gary Abrahams, Ivan Thorley, Carla Yamine, designer Adam Gardnir, lighting designer Nik Pajanti, sound designer Peter Brennan; Theatreworks, St Kilda, Melbourne, March 8-25

RealTime issue #78 April-May 2007 pg. 7