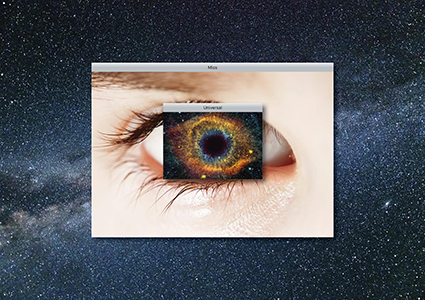

Miss Universal dances the Transmodern, with love

Andrew Fuhrmann: Interview, Atlanta Eke

Key image, Miss Universal

Atlanta Eke

Key image, Miss Universal

Atlanta Eke’s work tends toward the hybrid. It’s the essence of her choreography, drawing visual, sonic, new media and conceptual forms into new relationships of exchange with the dancing body.

“I’m probably more cerebral,” explains Eke, who last year won the inaugural Kier Choreographic Award. “The practice for me is concept first, image, relationship and then once we’re there it’s really a lot of learning.”

Is this a dialectical practice? Concepts are placed before and against images and relationships: the concept is transformed and ultimately transcended. But the synthesis, the thing which happens during the performance, remains haunted by what came before. This unsettled quality is a hallmark of Eke’s work. Those striking, unforgettable images—say, the troupe of naked women with black hoods obscuring their faces dancing to Beyonce in Monster Body (2012), or the slow-motion ballet for cars in The Death of Affect Restaged with a Return to the Japanese Nude 2017 (2015)—are shot through with intimations of something profound but elusive.

The work seems to invite interpretation, but no paraphrase can comprehend the experience. It always feels as if you’ve missed something.

For her latest work, Miss Universal, commissioned by Chunky Move, Eke cites the inspiration of thinkers such as Carolyn Merchant, Monique Wittig, Donna Harraway and the Spanish philosopher Rosa María Rodríguez Magda. It’s a diverse bunch, not easily reconciled, but Eke’s creativity is good at translating multitudes.

The work had its first incarnation earlier this year at Gertrude Contemporary. Pip Wallis, a former curator at the Fitzroy gallery, saw a short work of Eke’s—Fountain (2014), also at Chunky Move—that reminded her of the sculptor Claire Lambe, and she invited the two to make a collaboration.

“They were trying to figure out ways to exhibit their studio artists in different ways,” explains Eke. “I met with Claire and began this conversation on how we can work together and I came up with this Miss Universe idea, trying to appropriate the format of the Miss Universe competition as a model for another kind of cultural, transnational happening.”

That was in March of 2015. The work has since been completely revised for Chunky Move, but Eke is still attracted to the idea of an unconventional (or convention defying) theatre space, a space that’s more like a gallery.

“I guess the interest for me is the social ritual and that was why it was fun starting at Gertrude and having the audience in a choose-what-you-want-to-do kind of space,” says Eke, who has created work in a number of galleries over the last couple of years. “You’re asked to come in and do a 20-minute show in a gallery and people are just leaning against the walls and sitting on the floor, and it’s just like, ‘why can’t we do that more in a theatre?’”

Atlanta Eke, Fountain, It Cannot Be Stopped, 2014

photo Sarah Walker

Atlanta Eke, Fountain, It Cannot Be Stopped, 2014

Despite the attraction, she’s aware that dance audiences may not respond to the offer of freedom.

“It’s kind of a delicate thing,” she says. “We’re going to find out a lot about it by doing it. I want the initial entrance into the performance space to be a kind of uncanny experience. It’s going to be a replication of the space that they’ve just been in. There’s an interest there in a certain kind of violence: feeling like you don’t know what you’re supposed to do, undermining habituated behaviours. But, yes, there are a lot of performances which already have that freedom, and it has become a convention in and of itself.”

Once inside the space, Eke—along with performers Annabelle Balharry, Chloe Chignell and Angela Goh—is proposing an exploration of different ideas of the universal. Is it possible to recombine the fragmented moments of recent history as a new universalism? Is it desirable?

“What we’re trying to practice is transmodernism,” she says, with a nod to the work of Rodríguez Magda. “So, in relation to dance history, it goes modern dance, postmodern dance and now transmodern dance. I think this is how one could propose a new universality for today, to reclaim the sincere, progressive and positive aspects of modernity. We’ve been like, ‘Dance your memory of postmodern dance.’ And it’s the usual fragmentation. Let’s see what happens when we piece it back together.”

Atlanta Eke, Monster Body, Dance Massive, 2013

photo Rachel Roberts

Atlanta Eke, Monster Body, Dance Massive, 2013

This kind of focus on the conceptual level can make Eke’s work sound more difficult than it is. In fact, her work is best characterised by its humour. There is, for instance, the section in Body of Work which looks like (or rather sounds like) one long fart joke. Or there’s the infamous scene in Monster Body where she reclines like a painter’s odalisque in a spreading pool of her own urine.

To the extent that the work is difficult, it is not because of a deliberate refusal to communicate. Eke and her collaborators know how to create a powerful connection with the audience, something absent from so much contemporary dance. It is one of the paradoxes of her oeuvre that what can seem at one level like cynicism or critique, can also have an attractive naive quality, like an earnest yearning for progress, for a genuinely communitarian, feminist future. And what better vehicle for hope than comedy?

But there is something urgent and sincere about the work. It’s not necessarily emotional or expressive, but there is an insistence through which the need for action is underlined. In Miss Universal, this comes across as a preoccupation with the theme of love.

“The thing is about love,” says Eke. “So we have these conversations where we focus in on the individual and love and then out on this idea of love as this other undefinable energy that attracts everything in the universe together.”

Atlanta Eke, Fountain, It Cannot Be Stopped, 2014

photo Sarah Walker

Atlanta Eke, Fountain, It Cannot Be Stopped, 2014

For Eke, love is the force which enmeshes and interconnects. It encompasses all the fragments and fugitive lines of a world without an organising centre. It gives coherence to the chaos. But is this only an artist’s figure for the absolute spirit, a way of explaining the mysterious unfolding of her own dialectical avant garde transaesthetic practice? There is a sense in which every artist yearns to be Miss Universal.

“The mission is to produce something unknown,” she says, “which is in the journey where it goes from the theoretical, cerebral thing to the art thing. But there’s something tricky about that—how do you do that without alienating people?” Maybe the only sincere way of doing it—all corniness aside–is to admit that the answer really is love.

Chunky Move, Next Move Commission, Atlanta Eke, Miss Universal, Chunky Move Studios, Melbourne, 3-12 Dec

RealTime issue #129 Oct-Nov 2015 pg.