My RealTime years: art, writing & terror

Drama to postdrama

I cut my teeth for RealTime with an interview with playwright Deborah Levy (RT 11, p6 1996). Levy, who has since gone on to a successful career as a novelist, had reached a personal crisis point in theatre. “Theatre is obsessed with explaining every moment and its causation in a way that doesn’t interest me much,” she explained. “I’m not in the least bit interested in narrative in the theatre. I really don’t come to the theatre to be told stories that the playwright already knows.” These insights may seem outdated now but in the 90s they were still challenging. She veered away from the naturalistic, political dramas of her early career and wrote a series of non-naturalistic texts, such as The B-Files, in which, as I wrote, “any sense of gender essentiality or an individual authentic self are undermined during the fluid investigations of identity.”

Born in South Africa of Jewish and Protestant parents, brought up in England, Levy saw herself as “stranded between all those points with all of them trying to claim me as theirs. The idea that there is a pure culture in our contemporary world is totally untrue. Our society is impure — no wonder cultural identity is what everyone is talking about.” She was driven to jettison both ‘narrative’ and ‘character’ as being too overdetermined for her shakily determined world. “Naturalistic characters always come on the stage with too much baggage. They rarely allow the audience space to project onto. That’s why I prefer working with persona.”

These shifts in focus in theatre — from dramatic narrative to ‘distilled images,’ from deep character to swiftly transforming persona, from coherent identity to fluid multiplicity, from representation to presentation etc — were not new. Artists in Europe, Britain and the US had been moving in this direction for a couple of decades. By the time of my interview with Levy it was becoming clear that, as she put it, drama was a “dead and dying form that sits very uncomfortably with any kind of expression of the contemporary world.” However, in looking back at the shows I watched and wrote about for RealTime over the following 14 years, it seems to me that this uneasy terrain was still the one being explored and fought over in most of the works; and that the ones I found the most interesting included within their dramaturgy the terms of the conflict they engaged.

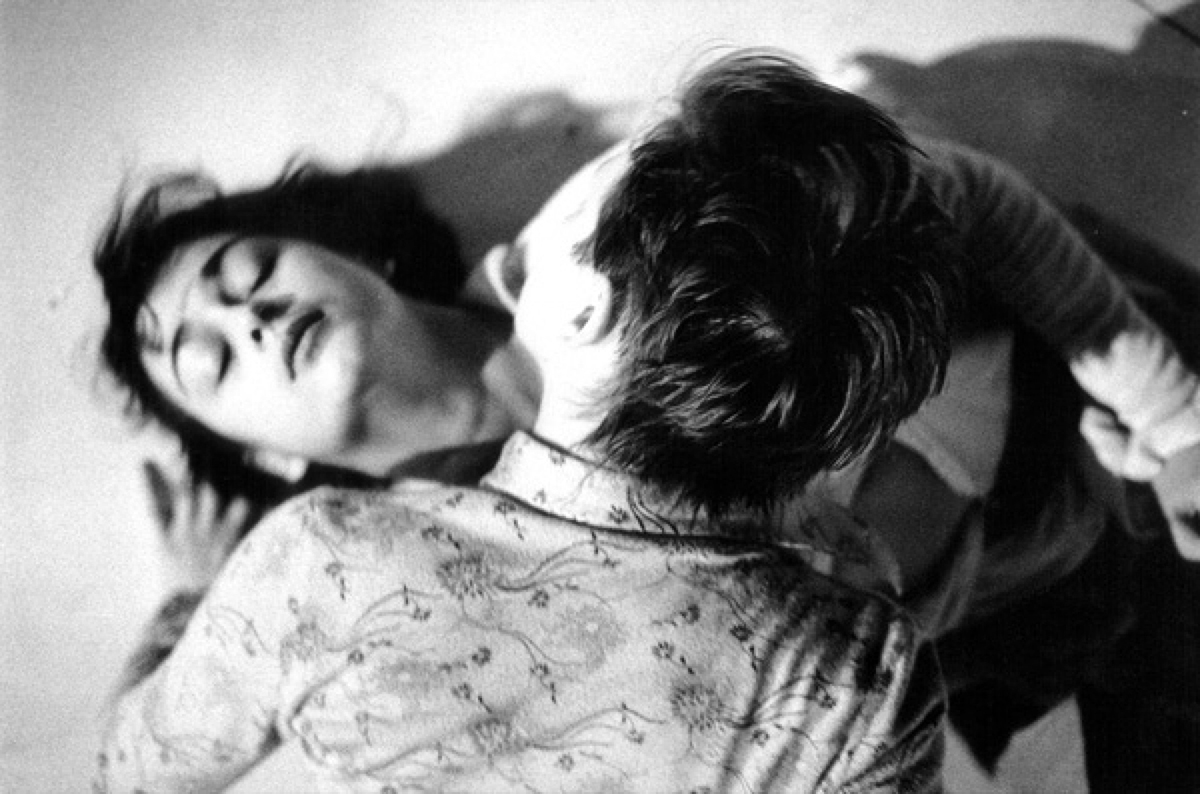

No-one is Watching, Meg Stuart & Damaged Goods (1996), photo courtesy the artists

Meg Stuart, No-one Is Watching; Saburo Teshiwagara, I Was Real — Documents

It’s not surprising that my first two examples come from that liminal world where dance approaches theatre (“Tanzteater,” Pina Bausch called it in the 80s), avoiding theatre’s ‘dead and dying form,’ bringing to it fresh investigations of the human through a heightened sense of the power and fragility of the body in space, and the perspectival shift of alternating stillness with barely controlled action-image. “Meg Stuart and Damaged Goods’ No-one is Watching takes place in an epileptic world,” I wrote from the 1996 Adelaide Festival. “The psyche, the society, the civilisation has been seized and is convulsing. Attempts are made by one or occasionally two of the figures within to connect with another, to express an emotion which has something to do with tenderness. Unfortunately, at the time, the intended receiver is not watching, possessed by a force that has little to do with love.”

The performance balanced on the fine line between the representation of a human condition and the shock of clear and present actions. “The dance for me was at its most powerful either in the fragments of states of being when no complete image was achieved or in the moments of suspension of action when the stage was filled with the memory of past events, or with the threat of what was to come. It was least interesting when dance became representational and traded off the audience’s empathy with what was being represented. It is always hard to watch madness being acted.”

Even the title of Saburo Teshigawara’s I Was Real — Documents (London International Festival of Theatre [LIFT] 1997) flirts with the desire for personal narrative (is this to be a story of someone’s life?), the promise of the real in an arena of pretence, and the confusion between represented past events with palpably present actions. “Documents of the time when I was real — for I am no longer?” I mused at the time. My memory of the piece now (and it has had a lasting effect upon me) is of its spareness, its sense of extended time and space, its magical configuration of human figures seemingly out of emptiness. “There are many dancers in Teshigawara’s company but the stage never seems crowded, the tendency always is towards emptiness, or clear focus upon one or two items. As a viewer, I am gently given the choice of entering and following, so that imaginatively I am travelling too.”

The work began simply and instilled its surreal world without effort. “Four men enter, put on berets then leave, enter, put on berets then leave, enter, put on berets then leave — no, one stays behind, fascinated with the moment of picking up the beret, bends, holding pose. This is the telescopic process that dream and memory utilise.” Teshigawara’s dancers were not dancing in any way that was familiar as dance. They were humans occupying space and forming images that triggered fleeting memories, and that suggested for performance ways of being present without needing justification from a rational narrative context.

Jan Fabre, I am Blood

Jan Fabre’s I Am Blood (Melbourne Festival, 2003) proved to be the extreme measure of the disturbance that the postdramatic could stir in the defenders of a coherent dramatic world view. I entitled my response to the show “The Anxiety of Formlessness,” and quoted the reviewers from the Melbourne dailies who reacted in horror, accusing it of lacking “any sense of selectivity, of form and structure, resulting in an indulgent presentation” (The Age), so that it presented only “a spectacular display of chaotic nastiness…poorly choreographed…a bloody shambles” (The Sunday Age). I agreed that I am Blood, and the shows by Teshigawara, Needcompany and Romeo Castellucci, works that I had written about for RealTime over the preceding years, “are not easy to absorb, impossible to fit into any recognisable structure. They feel carefully fashioned but without any underlying form; and maybe (horror!) this equates to surface without soul.”

My response was to meditate not upon the elements of traditional drama that the show was missing but upon what we saw before us and what it might provoke in us: “The show seems as much as anything to be a meditation upon the act of shedding and covering. The bodies cover themselves with armour, wedding dresses, ordinary clothes, only to take them off again and again revealing the vulnerable flesh (and blood) underneath. Steel tables are alternately used as platforms for human display and surgical benches for bodily desecration. I think of the jeeps and tanks and helicopters in Iraq, supposedly providing armoured protection to the ‘invulnerable’ US troops, but ripped away increasingly by bombs and missiles to expose the flesh of the soldiers underneath.” There was careful dramaturgical choice here in its “images and sequences of exquisite formality, set against sequences of seeming chaos.”

In his response to the irrational juxtaposition in shows such as this, Hans-Thies Lehmann coined the term “the aesthetics of poison.” He intended the term in a homeopathic sense: “An image of beauty, craving and desire is presented, but with the addition of a disturbing element, a vivid poisonous green tinge of colour…(which) spoils my enjoyment, while at the same time stimulating it to reach a different level of reflection.”

Being a Writer for RealTime

I had avoided reviewing theatre before I started with RealTime. How could I as an artist struggling to get my own stuff on the boards presume to assess the work of my fellow-artists? Keith and Virginia had from the outset cleared me from that concern: writing for RealTime was not to be a judgement of the work but a writerly response to it, allowing the show’s affect upon me to challenge me to write to it and thereby to open out into new associative musings. I learned on the job, mainly through the models provided by Keith and Virginia and other key writers in their own articles through the 1990s, particularly in the hothouse that was the RealTime daily response to the proliferation of the shows at LIFT97.

“I am aware of the ‘narrow grooves’ of my responses to the body of LIFT,” I wrote at the time, borrowing the metaphor from Paul Carter, “and of the danger that will drain its spirit. I see the inflexible fences I build across the irregular surface of a show, enclosing it in a way that is never healthy because it halts the drifting quality of a work of art.” It was the co-presence of other writers writing on the same shows (and others) that heightened my awareness. “As I read the articles of my fellow writers on the same event, I am led to reflect again upon what I might have written (or might have seen). ‘How do I see?’ has been ‘How do I write?’ for all of us as we steer clear of trenches already dug. We are saved by the diversity of cross-opinions. In fact, the writing of Linda [Marie Walker], Zsuzsanna [Soboslay] and Virginia [Baxter] often has for me the quality of a drift lane, not digging anywhere too deep, more interested in the ground beneath their feet as they travel.” Two thoughts arise from this experience.

1. Community

First, I felt again the power of community in art at the five-hour conversation between writers for the paper and artists at RealTime in real time at Carriage Works in October. I felt it for the first time as a writer at LIFT97 when our group of Australian writers joined up with several British writers to respond to the festival. More than anything, it was the opportunity to publish alongside one another a variety of responses to many of the shows: four different responses, for example, to Deborah Mailman and Wesley Enoch’s overwhelming 7 Stages of Grieving set alongside one another, each one a gem of writing, each finding new insights into the show to bring forth. What more could an artist want?

When occasionally I found myself disliking a particular show and trying to write to that response, I would discover in the same issue, several other articles discovering in the show delights and insights I had completely overlooked. One of the British writers (Gabriel Gbadamosi) attacked the Australian writers for their “hunger for an aesthetic” in our mainly positive responses to the German show Stunde Null. Whereupon, the following article by Keith included, in his positive response, a comment on Gabriel’s “quotable, cutting, epigrammatic style more in line with conventional British theatre reviewing.” These good-natured disagreements and agreements created within the paper the kind of productive dialogue out of which new ideas and new work can arise. Such a community of arts writing is to be treasured as our culture atomises by the day. In RealTime, the possibility was fulfilled.

2. Art and writing

The second thought has to do with the interplay between art and writing about art; or more specifically, the effect that a show could have on the very writing style of the responder. This was true throughout RealTime’s history — films, visual art, sound installations, performances: all drew from the writers writing that may not have been possible without the show as stimulus. In other words, what RealTime encouraged was not to trap every artwork in the tight, narrow language of ‘the review,’ or even ‘the academic interpretation,’ but to broaden the scope of the language of response in the light of the artwork’s unique act of communication. Many of the writers come to mind, but as an artist my joy has been that my own works have stimulated, for example, Jonathan Marshall to such powerfully poetic prose in his responses to two of my works, The Inhabited Woman and The Inhabited Man.

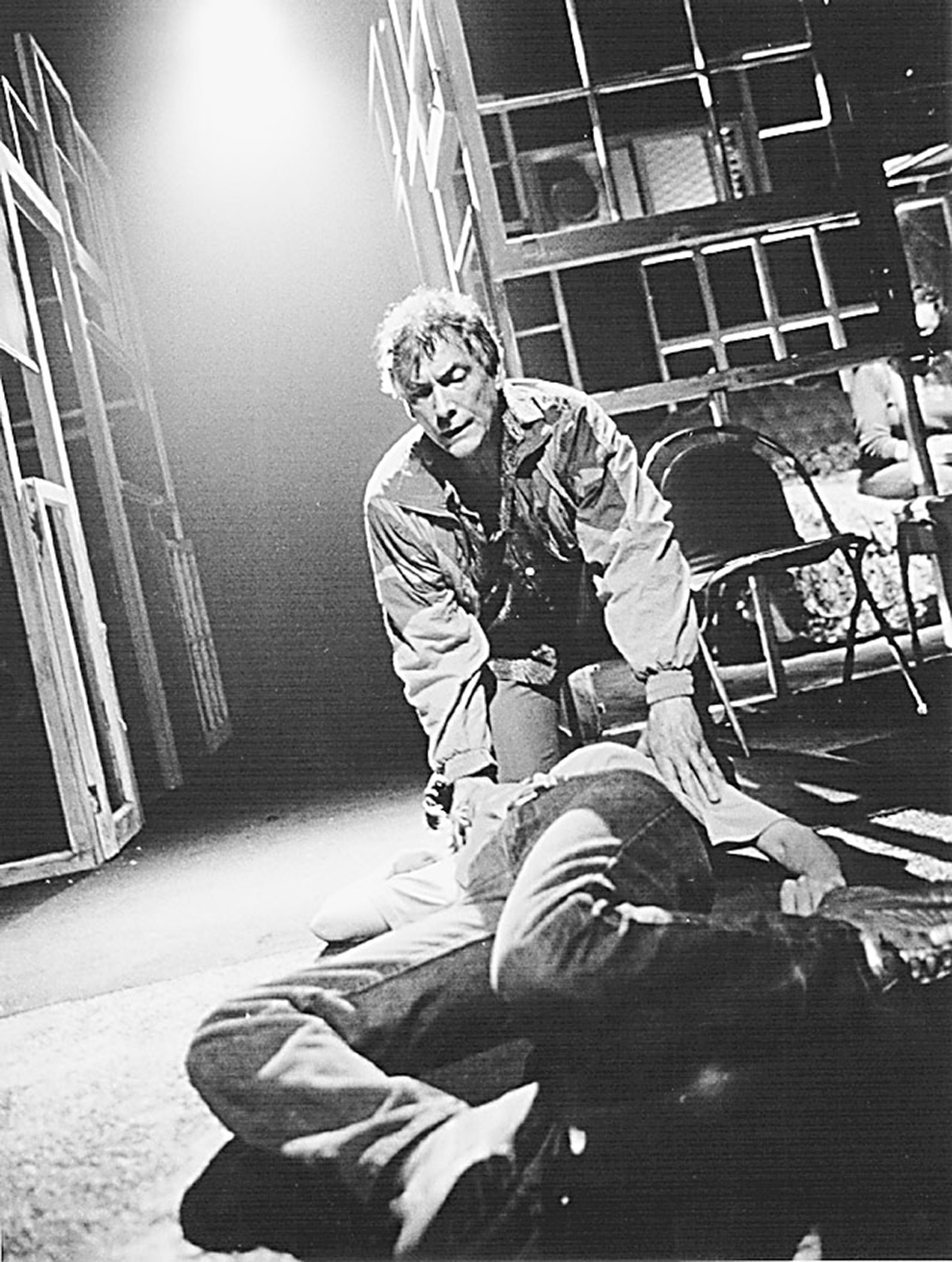

Ian Scott, Anne Browning, Slow Love (2002), Chamber Made Opera, photo courtesy the artists

My favourite example, however, has to be “From the cutting room floor”, the response penned by Virginia and Keith to the production of my play Slow Love at the Adelaide Festival in 2000. The play consists of hundreds of very short images separated by hundreds of blackouts. It is fragmentary and impressionistic and was my attempt at what I called “epileptic writing.” Their written response is a remarkable piece of epileptic writing in its own right. I delight in the article not because it simply praises the show; they include across the range of their fragmentary thoughts their own responses, the moments that remain with them, the lacks in show and production that they felt throughout, the associations they make to the wider culture, the responses of other writers, quotes from the show etc. It is an article that responds to the show by putting itself in the frame of mind that infuses the show itself. As co-writers, they transformed their style of writing; they allowed the art to create the language with which to write about it.

Politics and art/Politics in art

The conversation at the end of the afternoon at RealTime in real time ended on a rather sombre note — participants filled with trepidation about the future of art, especially performance, in these days when the political scene admits less and less room for Art in considerations of state. I thought back to other periods in my life when this had seemed to be the case: the Menzies years, the Fraser years, the Howard years, even the Hawke years. And my mind was drawn to certain of the shows that I have seen for RealTime, and the ways in which they have pushed politics to the forefront of the art in the face of lack of heed or outright hostility towards Art on the part of the politicians in power.

In 1996, shortly after THAT election when Howard defeated Keating, the Maly theatre from St Petersburg arrived at the Adelaide Festival with Claustrophobia. “On the night of the election,” I reflected (March 1996), “we were urged by politicians of both sides to count our lucky stars that we lived in a smoothly functioning democracy where a change of government can take place peacefully and without a drop being spilt. Well, yes. But something in me screams that we have allowed the reactionary party to crunch into power without a bang and with hardly a whimper.” Enter the young performers from the Maly, caught at a point when Russian society was going through its own painful transition from Communism to…what? “The overwhelming feeling,” I wrote, “is of a trapped generation, weighted down by the past, trapped in the present.” The point is that this lost generation took it on: tried to find a way artistically to express the disconnect between them and those in power, “beating out through the walls only to climb back in again to continue the fight.”

I remembered, too, the determined commitment of Australia’s Not Yet It’s Difficult (NYID) with their terrifying version of state control in K, and their chilling depiction of surveillance techniques in Scenes of the Beginning from The End. I subtitled my article on that company “The Danger Zone,” and marvelled at its consistently “merciless exposés of certain tendencies in contemporary civilisation.”

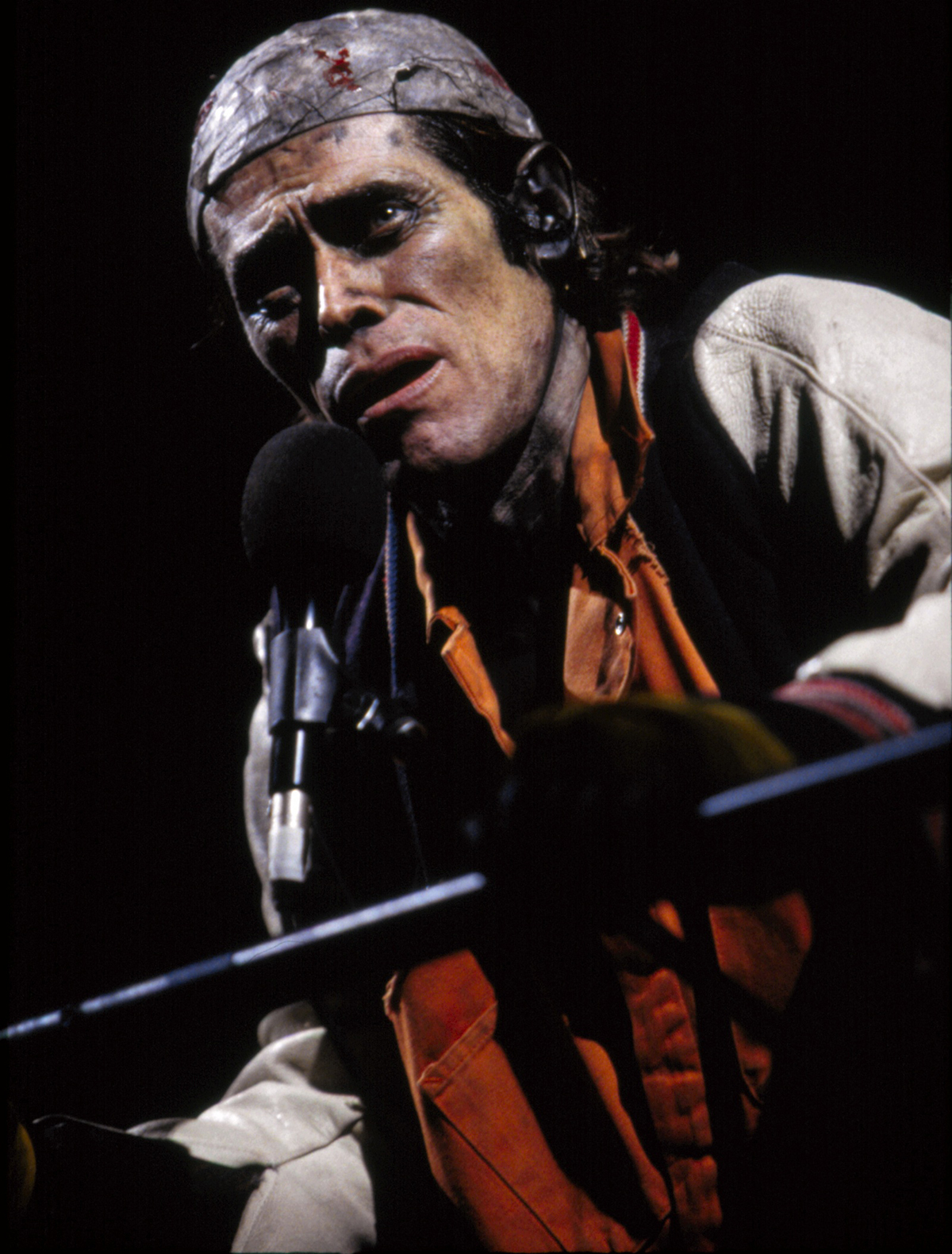

Willem Dafoe, The Hairy Ape, The Wooster Group, (2002), photo courtesy the artists

I wrote about The Wooster Group’s The Hairy Ape (“Terror, Theatre and The Hairy Ape,” February, 2002) five months after the attack on the World Trade Centre. The group’s version of O’Neill’s play highlighted the insurmountable disparity between those who work to keep the wheels of society moving (the ordinary workers), thinking that they therefore move the world, and those who wield the real power invisibly behind doors in board rooms and drawing rooms. I read the production through the lens of a remarkable book by Anthony Kubiak called Stages of Terror. “The book is an attempt,” I wrote, “to write a history of theatre as terror. More than that, it argues that theatre’s ability to name that terror at the base of life has always been one step ahead of the society in which it has played. That the culture of perception which it has engendered in all its forms has, far from mirroring its society, found ways of developing for that society an understanding of the terrifying interplay between power, production, coercion, ideology and identity—an interplay that is based upon the application of terror and its close allies, violence, pain and panic. This may seem to be a bleak reading of theatre and of history itself. I don’t think so. It is bracing to witness with clarity the powers that cloak themselves in all sorts of coercive masks within our society and it is true that theatre above all is the artform that can, that has and that should reveal those masks — even if it does so (as in Restoration comedy) by applying them even more rigidly.” The Hairy Ape revealed the masks cloaking the State terror.

So too did Schauspielhaus’s Stunde Null which I saw at LIFT in 1997. It was among other things a play about a school for politicians, who act like children and are treated as such as they learn the gobbledygook language of politics. “What do politicians really expect us to believe?” I asked. “They lie, they know they lie as they lie, and they must know we know. And the media is complicit in this constant rending of language and meaning. They make the show of attempting to reveal, they push so far but they never never tip the bucket. Someone needs to tip the bucket. Stunde Null does so.” And it did so through laughter, unstoppable laughter. “Politicians have been attacked with laughter and corroded with irony since Aristophanes. Laughter in that form is a revolutionary force. It refuses to accept the world on the terms that the politicians or the daily media present it to us. It turns the world upside down, allows us another way of looking at it.”

And this in the end is my feeling about theatre in a time when politics takes no notice. What all these companies did was to force politics to take notice because they spoke to politics, rejected being a ‘mirror’ for society, refused to turn inward, remained aware that theatre’s blinding vision is a revelatory force. “Just as pain and terror both cause and effect each other,” wrote Kubiak, “so, in its articulation of terror, theatre operates as both cause and resistance to that terror and oppression.”

–

Read about Richard Murphet here.

Top image credit: I Am Blood, Jan Fabre, photo courtesy the artists