Nam June Paik: bad video, poor performance

Philip Brophy, 10th Anniversary Retrospective of Nam June Paik

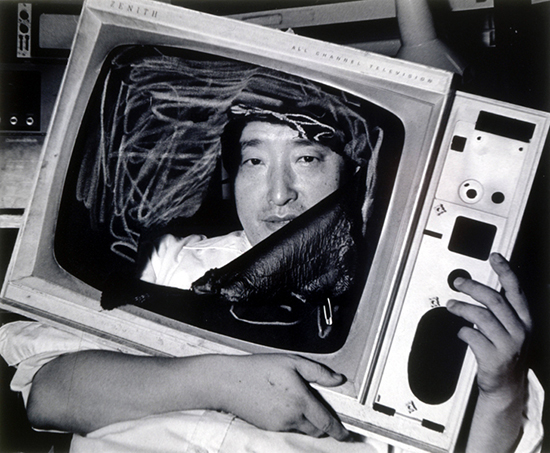

Nam June Paik in New York City, 1983

Photo by Lim Young-kyun

Nam June Paik in New York City, 1983

The key fuel which energised the 20th century shift from ‘art object’ to ‘post-object’ was performativity. Think Duchamp donning alter egos, Pollock painting in real-time, Klein directing paint-covered nudes, Nauman videographing himself. Of course, a host of ‘new objects’ were made in the process, defining new media along the way. Video art is likely the most notable outcome, born from half a century of furrowed brow mirror-phase enquiry, crucially citing the artist not only as performer, but ‘post-object’ performer akin to his or her ‘anti-material’ brethren.

Nam June Paik is routinely touted as the godfather of video art. It’s not a term he came up with, but one that he neither denied nor avoided. Paik—like Duchamp, Pollock, Klein and Nauman—exploited himself as matter and used himself as material. Specifically, he ghosted his presence within the comparatively ‘immaterial’ phosphorescence of the CRT video monitor and its ‘technostic’ transference of magnetic videotape. Conceptually reflecting on video’s innate presence as a form of new media, he further networked these strategies into a wide array of multi-media events, constructions and strategies. For this, he is undoubtedly an important historical figure. The two-part exhibition at the Watari Museum in Tokyo, 2020: Who is the one grinning ?+?=??, celebrates Paik’s legacy and works towards maintaining his place in history.

And so the Watari Museum should. The institution was founded as a private entity in 1990 by Shizuko Watari, following the establishment of Galerie Watari some 10 years earlier. The museum boasts a flashy bubble-era architect-designed frontage in Shibuya. It specialises in a robust representation of Japanese contemporary art informed by internationalist modernism and postmodernism. Nam June Paik staged some of his most ambitious works at both the Galerie and the Museum on numerous occasions, and this exhibition revisits those canonical works from its collection. As such, the exhibition promotes Paik’s history as braided into the Watari Museum’s supportive infrastructure—which is worth acknowledging in Japan where staging contemporary art has always been a vexed enterprise for difficult artists.

Looking another way

Now, much of what I’ve said above easily sidles up to orthodox historical assessments of radical modernist ‘post object’ new media production from the latter half of the 20th century. Let’s move past clean didactic check boxes to murkier tendrils of artistic evidence. Paik’s key role in the Fluxus venture—especially in promoting its internationalist multicultural spread—enabled him not only to travel on the movement’s dispersion of performativity, but also to apply its indeterminate, collective, interactive and open-ended processes to his solo works. But sharply considering this in the Watari Museum exhibition, a conundrum presents itself when forensically assessing the videos. Art history usually gets away with Chinese Whispers, lost documents, destroyed works and bad photographs. Indeed, the mythos of Fluxus is sealed in old black and white snapshots of men in suits doing messy, wacky things. Conversely, Paik’s work is there in all its videotaped RGB glory. In a YouTube era (a cliché that here I am forced to use) where historical artefacts get splattered online in random fragments—which can sometimes illuminate through the veracity of their innate materiality—watching Paik’s videos and performance documentations generates conflicting impressions.

The first lies in the cultural overlays which will always energise art beyond its mad authorial dictates. Paik (and his proselytisers) will make claims of radicalism, but in a post-war media realm, only a fool (or a curator) would persist in honouring an artist’s post-object/new-media vision while ignoring how the artist’s chosen technologies operate outside the art gallery. By inference, Paik is associated with the medium of television and video becoming what they are as if by his provenance, and as if technological society needs such visionaries. Despite the mantra-like trail of paragraphs which mythologises Paik’s ‘invention’ of things like television interventions, video synthesisers, global satellite broadcasts and electronic intercommunications, I see only default-position videographic aesthetics played out again and again. Roughneck chroma-keying, insipid colour-wheeling, and lo-fi parabolic patterning document less a renegade incursion of media protocols and more the absence of a responsive eye. Particularly throughout the 80s and 90s—two decades across which televisual, digi-cine and pixel-dependent aesthetics developed in leaps and bounds—Paik’s work looks like community TV slots from the late 70s.

On the second floor, a large space contains Paik’s Earth Theory (1990), previously installed here in 1993. It’s a faux tree sprouting a slew of various sized monitors. Some are synched, playing the same tape; others play separate non-synched tapes. The content seems archival even for the time, playing as it does fragments of footage Paik would have produced across the preceding decade. One monitor here is allowed sound. In keeping with Paik’s idea of television being media maybe moreso than video per se, it appears to contain fragments of the type of ‘conception and co-ordination’ he did for the ambitious intercontinental real-time live tie-in/broadcasts like Good Morning Mr. Orwell (1984) and Wrap Around The World (1988). Here, one piece really stands out: Transpacific Duet (1988), which features casual audio-visual flipping and mixing of Ryuichi Sakamoto in Tokyo (performing his version of the Okinawan ballad “Chin Nuku Juuishi”) and Merce Cunningham improvising dance movement in New York.

Cage Forest / Forest of Revelation (1990), Nam June Paik

Paik, Sakamoto, Cunningham

Sakamoto’s song originally appears on his album Neo Geo (1987): a gaudy hi-tech decimation of a truly beautiful song, its only saving grace is the embarrassing tastelessness of its 80s production. But for Transatlantic Duet, all the Trevor Horn drums and Spandau Ballet slap-bass are absent: it’s just Sakamoto on synth pads and three beautiful Okinawan madams warbling while striking their shamisens in slow-metered clockwork. Against this minimal melodiousness, waves and washes of voltage-controlled filtering of abrasive noise and crackling straight out of the IRCAM textbook sweep throughout the ethnographic fluttering of the delicate Okinawan modal. Cunningham executes one of his amazing ‘I’m-not-really-here’ explorations of space with his lilting metamorphosings of positions. Observing his movement is like watching an hour of 10 people waiting for a bus, all compressed into a single corporeal movement. The mix between these two events is magical. It’s also strangely prophetic of Sakamoto’s collaboration with Alva Noto for records on Raster-Noton (2002-2011) and portions of the score to Alejandro González Iñárritu’s The Revenant (2015).

Having later re-watched the complete satellite events of Good Morning Mr. Orwell and Wrap Around The World (presented earlier in the first part of the exhibition), I can only say that Transatlantic Duet is an anomaly: the rest of both shows is mired in dated Downtown NY insularity and hipness. But what I’m most struck by is how this transcultural merger of what Paik termed “global disco” unwittingly produced a complex intermedial audiovisual work unlike anything else evidenced on the spray of monitors at the Watari Museum.

Returning my experience

The second confounding factor in Paik’s technological self-hagiography lies in the bald badness of his performance. On the third floor, a variety of works illustrate Paik’s longstanding performance relationship with Joseph Beuys, technically spanning 1961 to 2006. Various monitors play famous works like Coyote III at Sogetsu Hall in Tokyo. In it, Paik doodles at the piano playing classical excerpts, while Beuys stands at a microphone intoning concrete poem-like grunts and phonetic syllabic stabs. The piano playing is pedestrian, and Beuys has to be the worst performer I’ve ever seen: entirely self-conscious while megalomaniacally convinced of his intellectual grandeur. It’s like watching your dad doing karaoke and being really really serious about it. It’s neither engaging post-poem-performance nor charismatic spectacle. Is this a subversive hallmark of Fluxus performativity—being so bad that one is transported to a liberated plane of unhindered possibilities? I can buy the theory, but I’m returning my experience.

On another monitor with headphones, Paik performs Farewell To Our Beuys (1986) at Watari Museum. The piece is a requiem for the deceased Beuys, Paik’s compatriot in forming their ‘Eur-Asia’ conceptual continent based on their Fluxus-derived performances. Paik slowly moves around a grand piano and hammers nails into it, symbolising it as a coffin and finally planing the lacquered keyboard lid. All the time, he’s checking that the camera is in the right position to ‘document’ this incredible event, as if history is being made. It sure isn’t. He can’t even hold a hammer or planer properly, and he certainly isn’t listening to what he’s producing. Most offensively, he patronisingly directs a seemingly conservative woman from the audience to help him, getting her to ‘listen’ to the amazing sound world arising from this intervention into the history of classical propriety in the name of his and Beuys’ performative legacy. As the sloppy thuds reverberate the piano strings inside, the polemic rings hollow. A high schooler, a drunk or even your karaoke dad could make more interesting sounds banging up a piano. This heightened artlessness I see time and again when contemporary artists ‘revisit’ the performative world of the post-object. I also hear it when many a classically-trained musician attempts improvised sections in a scored composition.

Digesting all these works at the Watari Museum—particularly the post-object new media works moving beyond Paik’s earlier fascinating deconstructions of TV cabinets and CRT monitors—I can cerebrally and historically comprehend his playful concepts of “feed back & feed forth” and “Present > Infinite.” But I can also perceive and audit a surfeit of bad video and poor performance.

–

10th Anniversary Retrospective of Nam June Paik, 2020: Who is the one Grinning ?+?=??; Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, 17 July–10 Oct, 2016; 15 Oct, 2016-29 Jan, 2017

RealTime issue #137 Feb-March 2017