Narcifixion: Watching the narcissists

This is a review that started out as a brief response, but its subject matter felt too important to treat lightly, a risk that Narcifixion itself takes as a stylishly propulsive entertainment with a simple message – in effect, ‘beware screen-driven narcissism, it’ll destroy you.’ I found myself wanting to honour the makers by detailing the logic, as I see it, of the work’s construction and the nature of its vision.

Mashing “narcissism” with “crucifixion” for his title, choreographer-director Anton readies his audience for Narcifixion’s account of self-crucifying self-possession. It’s a common belief that we’re living in an era of rampant narcissism brought on by the unfortunate co-emergence of me-first neoliberal capitalism and social media platforms. On the other hand, narcissism is a necessary and highly complex component of psychological development and survival, manifesting in many ways, good and bad and, in extremis, a serious affliction.

I wonder, therefore, where ‘on the narcissism spectrum’ each of us sits: from apparent zero in some to the uneasy balancing of self and other in many of us, to the deceptive cover that is passive aggression, to the “controllers,” to narcissism’s full-blown realisation in attention seeking, power grabbing egotism driven by fear, conscious or not, of utter inadequacy? What will Narcifixion tell me?

Sorry to miss the performance in-theatre, I nonetheless had the advantage of watching a live stream of the final performance as well as a subsequent re-viewing. Save for distant images of a very wide stage, the work on screen was delivered with a finely lit and shot intimacy highly apt for the subject and for observing the precision and dynamism of the dancing.

NARCIFIXION AT WORK

From darkness, green warning beacons signal furiously, their agents barely invisible. From silence, one voice and then two intone ‘me’ in an impassioned string of distorting variations against a sustained grainy drone that soars into Vangelis-Blade Runner organ-synth that says sci-fi, confirmed with a flood of blue light revealing the two signallers (Anton, Brianna Kell) beneath an ominously pulsing electronic eye that presumably surveils them. Identically uniformed in flexible plastic tops and glass-visored helmets, the pair move in neat synch, the flow now and then interrupted by seeming mechanical faltering. Something is not right with these perhaps less than human beings, cyborgs maybe, and presumably the narcissists implied by the work’s title.

They soon appear real enough. To a trumpeting fanfare and bathed in red light, they formally remove their helmets and wrap-around shades, briefly mirror each other with smiles, muscular posturing and outstretched fingers that agonisingly strain to touch the other. Failure results in jerky agitation. Peeling off their tops (like swaying, skin-shedding snakes), they are even further freed of the outward shell of purpose but, curiously, sink to the floor.

Immobilised, face-down they gradually revive in an elegant micro dance of fingers, new life that quite gradually extends to arms, to bodies sitting, swivelling, to bodies, unfortunately, on backs like upturned insects racked by passing tremors. The further the pair is removed from the protective anonymity of uniform, of routine, the more naked they are, the worse their condition — narcissists short of the fuel provided by admirers?

Seemingly half-conscious, the couple rise. Ambiguous poses (some heroic, some like beach fashion modelling) slip into supple movements, increasingly one-hand-led, and escalating manically — replete with indeterminate signalling and sporadic jerkiness — until pulled to a halt. They peer serenely into the palms of their raised hands as if into unseen mirrors, and then, in a gentle turn and sway, hands lowered, look down on them as if gazing into water like the Narcissus of myth.

The selfish pleasure of narcissism demands constant refuelling; if not met anxiety ensues. With shocking suddenness, the pair’s hands turn on them, striking, pulling, spinning, vibrating them, until two becomes one, a four-armed, strobed, panicked creature fixated on mirror-palms that yield no sustaining sense of self. Exhausted and entangled, body against body, in a slow circular walk the pair refuse eye contact and touching comes to nothing in a sad little disengagement.

A new phase ensues, one of individual endeavours. He tries to communicate with her. First, it’s casual, a smile, an ‘Aaaah,’ then an indecipherable deep-throated utterance, then a cocky little circular dance — an invitation? The display grows grotesque, his t-shirt pulled up, a cartwheel, high kicks, failure to connect, a tantrum — narcissistic rage. Exhaustion.

It’s her turn. She carries a silvery, transparent plastic sheet the height and width of her body. It mirrors her gaze and movement in a slow, intimate dance between self and an image inviting curiosity and attraction, but then fixes stiflingly to her. The dark clattering of the amplified material is claustrophobic. There and not there, she is eventually nothing more than a fading image. Her mirror dance a narcissistic dead-end: a mere image cannot sustain self.

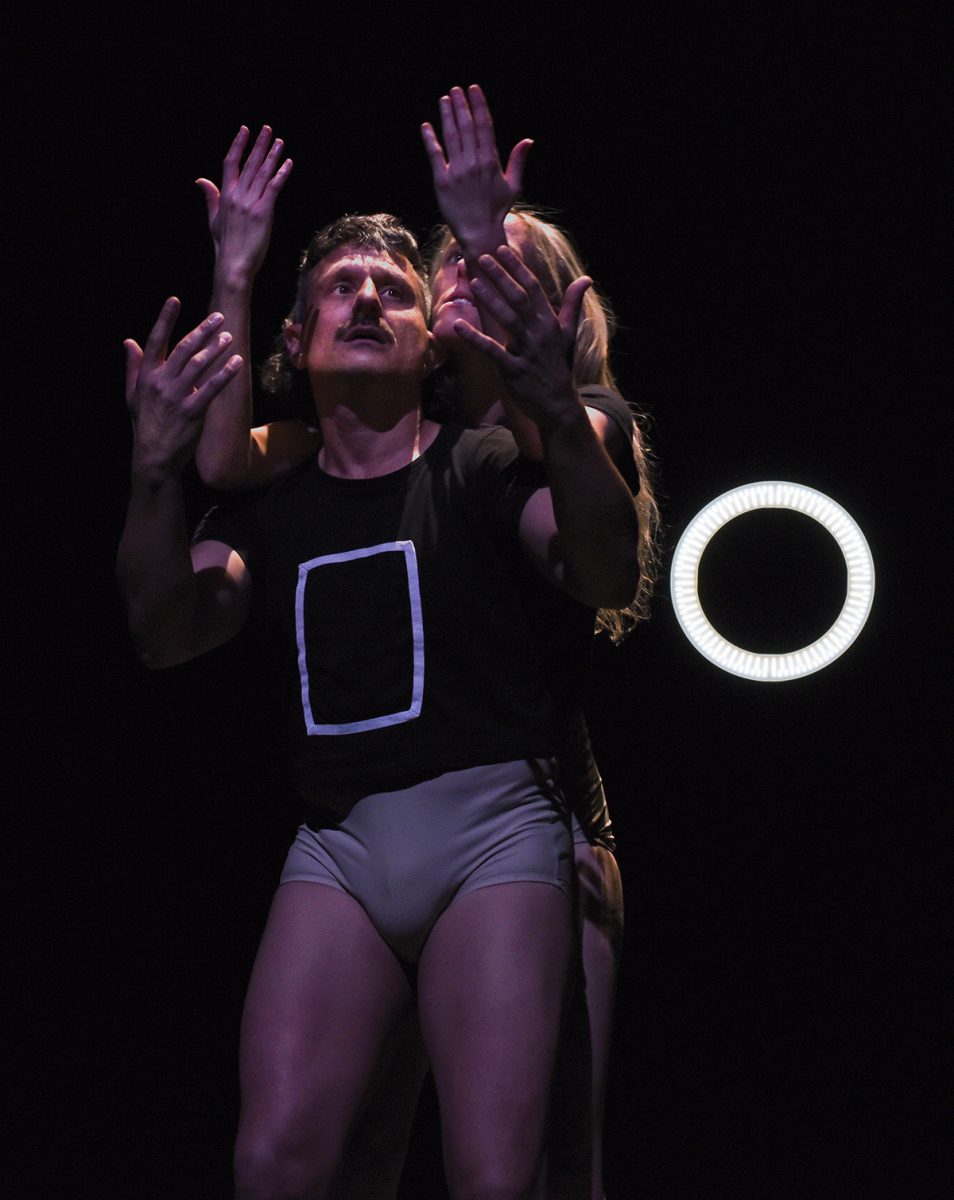

Another attempt to secure that self is announced with a darkly underscored, cicada-like beat. Standing before the ‘eye’ each neatens their hair, checks the other’s face, and together step into a spot-lit space, suddenly aware of an audience. Like fashion models they venture into a rehearsal of stylish strutting and then loping across the stage, hyper-smiling, pulling off t-shirts (branded with a square version of the ‘eye’) and settling into a ludicrous show girl promenade and, as the music dips away, embarrassingly exhaling overt groans of pleasure and self-congratulation, climaxing in an ‘Aaah!’ of joint approval, heads exultantly thrown back.

Such rare if empty success, free of now anticipated breakdown, prompts more exaggerated exertion, with a growing sense of omnipotence. A dark drum beat glides deep into a throbbing pulse introducing a protracted, bigger than life, hyper-articulated disco sequence that progresses with supreme confidence, faultless synchrony and increasingly expansive moves, dance as pure narcissistic display, with none of disco’s double offering of individual interiority and crowd communality.

The hand as mirror motif makes a brief appearance, integrated into the dance, before the desire to break out of the single self, to once more touch, recurs exactly as it first did, bodies awkwardly angled towards each other, fingers fluttering in near connection, stilled bodies helplessly vibrating. The pair break out, walking then dancing into proud recovery. But this too is doomed. They wind down, depleted, the world darkening around them, hands outstretched but palms now turned down, reaching out as if blindly into nothingness as a haunting oceanic swirling thins out into silence.

WORRYING AT NARCIFIXION

It’s a grim ending, this in-effect blinding, a cruel fate for a pair fixated on sight, on the gaze received from their mirror selves and imagined admirers. Are we complicit in this cruelty? While we’ve scrutinised and laughed at the pair’s self-crucifying behaviour, there is no way out for them in this scenario, or for ourselves.

Anton writes, “This union of words (Narcifixion) is a warning against getting too caught up in your ‘virtual’ identity.” But is this sufficient? If narcissism is a closed circuit, so is Anton’s critique of it, a vivid, exacting portrayal of a compulsive condition and its escalating pathology as the pair seek out new ways to reach impossible fulfilment, but throughout within that closed loop of grandiose effort and abject failure. What if one of the pair were eventually ‘unplugged’ instead of doomed? Which points to one of the stranger dimensions of the work, the absence of a dynamic between the two figures.

Anton describes Narcifixion as “a dance for two singular characters caught in a constant state of exhibiting and observing themselves.” Just how ‘singular’? Except for the conventional gender distribution of the two solos (the male as extrovert mate-seeker; the female locked in her mirror gaze), these narcissists are otherwise undifferentiated, save in appearance, dancing in exacting tight-knit harmony, in a duet of sameness without opposition or counterpoint (might one narcissist sooner or later strive to outcompete or demolish the other?). Is then the narcissism of our era exactly the same for one or two or three or more of us?

This absence of differentiation underlines the unresolved hybridity of a work that looks like dance theatre (the elaborate sci-fi-ish set-up of the opening, not returned to, the intensifying pattern of release and breakdown, the contrasting solos that have no other ramification) but inclines to a series of lightly themed, abstracted states of being, a relentless dancing for dance’s sake, which can at times be thrilling; at others it feels that Narcifixion could just keep going on.

Driven by the compelling logic of intensifying self-obsession and self-destruction, realised with meticulously executed dance, comic self-aggrandisement and the pathos of failed connection, Narcifixion is cogent and variously funny, acerbic and affecting, but too narrow in its vision of the condition it harshly critiques. What, in the end, are we meant to feel about its narcissists? That they deserve their doom? That we’re superior to them — because Narcifixion has refused to implicate us? That we see no way out?

I appreciate having been provoked by Narcifixion, and enjoyed the opportunity to view it more closely a second time. Viewed onscreen, the production’s eerie, no-where ‘set,’ comprising only highly effective lighting (Steve Hendy) and spare costuming (Brooke-Cooper Scott), was reinforced by composer Jai Pyne’s texturally rich, dance-triggering score and its chilling silences. Anton and co-choreographer Brianna Kell danced admirably as if their narcissists’ lives depended on it, in manic survival workouts with locked-in look-at-me smiles demanding infinite reward.

—

FORM Dance Projects & Riverside Theatres, Dance Bites 2021: Narcifixion, director, choreographer, performer Anton, choreographer, performer Brianna Kell, composer Jai Pyne, lighting designer Steve Hendy, costume Brooke Cooper-Scott, livestream team Denis Beaubois, Martin Fox, Dom O’Donnell, education consultant Shane Carroll, producer Anton; Riverside Theatre, Parramatta, May 13 – 15 2021

Top image credit: Narcifixion, Anton, Brianna Kell, photo Heidrun Löhr