new music: challenge as fun

matthew lorenzon, mona foma, hobart

Brook Andrew, The Cell

photo courtesy of the artist and MONA, Museum of Old and New Art, Tasmania

Brook Andrew, The Cell

AS THE SUN SETS BEHIND THE MOUNTAINS OVERLOOKING SULLIVAN’S COVE, A GREY BALL, FOUR METRES IN DIAMETER, BOUNCES INTO THE AIR. ITS AERIAL EXCURSION IS FOLLOWED WITH LAUGHTER AND SHOUTS BY A CROWD OF ADULTS AND CHILDREN CLAMBERING FOR A CHANCE TO CHANGE THE GLOBE’S ERRANT PATH. THE SCENE WOULD NOT BE OUT OF PLACE IN A TELECOMMUNICATIONS ADVERTISEMENT, EXCEPT FOR THE STATIC, FEEDBACK, CAREENING SINE WAVES AND EXPLOSIONS BLASTING FROM A NEARBY STAGE IN RESPONSE TO THE BALL’S MOVEMENTS. JON ROSE’S INTERACTIVE BALL PROJECT EPITOMISES MONA FOMA. AS ROSE PUT IT, “PEOPLE HAVING FUN MAKING EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC.”

Providing a playful environment in which people can enjoy contemporary music is essential to MONA FOMA curator Brian Ritchie who seeks to share the visceral excitement he felt upon hearing Edgar Varèse’s groundbreaking 1931 percussion piece Ionisation at age 10. “It was the first piece of contemporary classical music I heard,” Ritchie recalls. “It absolutely blew my mind.” With the rhythmic pounding of Ionisation providing one of the quieter moments of Speak Percussion’s opening program, Ritchie’s curatorial rationale was put to the test.

Speak Percussion, MONA FOMA

photo Sean Fennessy, courtesy of MONA, Museum of Old and New Art, Tasmania

Speak Percussion, MONA FOMA

speak percussion

Entering Princes Wharf Shed No.1 at Sullivan’s Cove through the airy seaside courtyard, wandering to the main stage past the Interactive Ball Project, Indigenous artist Brook Andrew’s inflatable art work The Cell, the irresistible aroma of catering by MONA chefs, and a row of table-tennis tables, it was hard not to feel enchanted and receptive. “You have to make the environment comfortable, so people don’t feel excluded, like they’re on the outside,” Ritchie explains. Approaching Speak Percussion’s setup on the main stage, it became evident that Ritchie was not using a figure of speech. Six batteries of gongs, bongos, toms, bass drums, cymbals and assorted non-traditional percussion instruments encircled an audience lazing expectantly on pink, purple and black beanbags. Percussion ensembles have a long history of playing “in the round,” or spaced around the audience, but rarely include some of the best festival food and an artistic jumping castle so close at hand.

Moving around the space or perched contemplatively on their beanbags, the rapt audience sat through the epic four-hour program (spread over two days) with the informality of a rock festival and the hush of a concert hall. This is just as well, as Speak Percussion’s sound engineers did not compromise the performance’s amplification for a potentially rowdy audience. As a result, the gently undulating marimbas and distant-sounding gongs of Liza Lim’s City of Falling Angels invited close listening, drawing the audience into what Speak Percussion’s Artistic Director Eugene Ughetti describes as Lim’s “hyper-emotional” musical language. The world premiere of Flesh and Ghost, Anthony Pateras’ study in crescendi, explored the space between gently clattering glass and roaring cymbals. The shocking assault of Xenakis’ Persephassa was as physical as it was aural. Xenakis’ ear-splittingly loud bongo rhythms darted around the space, wrapping the audience in a pointy, threatening cocoon that, thanks to the otherwise welcoming atmosphere, scared away only a few children.

Fifteen performers, 450 instruments (which almost missed the ferry), and eight Tasmanian, Australian and world premieres later, Ritchie was willing to declare the “huge risk” of Speak Percussion’s program a success. “The audience were carried by it, they didn’t baulk. We purport to be something: edgy, presenting new music, and sometimes you have to deliver.”

glocal collaborations

Though Sullivan’s Cove was settled in 1804 to defend against foreign exploration, at MONA FOMA the precinct functions as a launch pad for the discovery of local and international musical traditions. In particular, collaborations between Asian vocalists and Australian instrumentalists provided two of the most exciting contributions to the festival’s timbral palate in performances by Chiri and Cambodian Space Project.

Chiri’s Bae Il Dong perfected the Korean Pansori vocal style by singing at a waterfall for seven years. Ranging from swallowed, rumbling bass tones through an explosive, fraying tenor range to a howling falsetto, Bae Il Dong’s vocal skill was complemented by Simon Barker’s Pansori-inspired drumming and Scott Tinkler’s trumpet improvisation.

Cambodian Space Project’s Srey Thy honed her voice through five years of singing in Phnom Penh karaoke bars. With an Australian backing band she finally brings the bold tone and gorgeous prolonged nasal stops (“m,” “n” and “ng”) of Khmer singing to Australian audiences. Srey Thy’s expert execution of Khmer rock and roll classics and original songs paid a worthy homage to 1960s and 70s Khmer rock and roll pioneered by the singers Pan Ron and Sinn Sisamouth.

Drawn in by the playground of Princes Wharf Shed No.1, the audience was then encouraged to strike out across Hobart to the city’s many historically fascinating festival venues. Walking or, if you are lucky, riding one of Arts Tasmania’s free Vanmoof Artbikes past the heavy 1820s stone buildings of Salamanca Place, c1900 Federation houses and modernist Government buildings, you’re left to ponder the importance of place to art production. Again, contributions from Asian performers and artists provided the festival’s most striking engagements with context.

Hong Kong New Music Ensemble’s hypnotic Sound Cloud (Gong III) installation and performance filled the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery’s Bond Store with dozens of Arduino-powered blinking lights and piezo buzzers. As the 1826 warehouse was originally used for storing tobacco and spirits, it was fitting that composer Samson Young used the space to evoke Chinese miners’ experiences of smoking opium in the late 19th century Tasmanian tin fields. As piezo note clusters gently undulated, the slowly blinking lights signalled flute, violin, clarinet and sheng performers to play sequences of pre-determined notes, their vibrato melding with the gentle harmonic beating of the piezo sound cloud. Encouraged to wander through the space, the audience made the most of the profoundly differentiated sound experiences of the furthest corners of the dim, dusty, low-roofed warehouse. Even humming along on its own, without performers, the installation was eerily hypnotic. One boy, perhaps channelling the claustrophobia and very real dangers of 1870s mine shafts, exclaimed “it’s death-defying in there,” adding that he “even saw a ghost.”

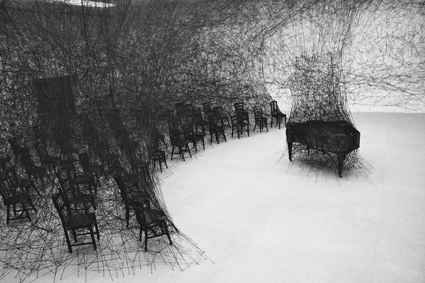

Chiharu Shiota, Biel Klavier

photo courtesy the artist

Chiharu Shiota, Biel Klavier

Japanese artist Chiharu Shiota’s In Silence presents a desecrated piano within the desecrated, heritage listed brick church that is the inner-city gallery Detached. Black wool is woven around the charred remains of the piano and high up into the vault above it. Shiota’s installation springs from a childhood memory of seeing a burnt-out piano in the remains of a neighbour’s house fire, a sight that has made her feel “overcome with silence” ever since. While the sight of the silenced piano carved a sacred, silent space in Shiota’s imagination, her woollen desecration of the church, no matter how still and picturesque, shows memory’s power, as an active, disruptive noise, to silence the present.

shards of glass

In contrast to Shiota’s burning stillness, Tasmania’s saxophone quartet 22SQ complemented the silent geometricity of Hobart’s Baha’i Centre with their exquisite control of dynamics and rhythm in works by Philip Glass. The SSQ2 performance was followed by Brian Ritchie’s interview with the composer. Like many of his 60s contemporaries, Glass looked away from institutionalised art music and towards Hindu and Buddhist philosophies to find new ways of composing and listening. In the interview it was evident that his earlier interest in the musical implications of those philosophies had passed over to their pedagogical traditions. Glass regaled the audience for half an hour on the importance of gurus in education and the importance of learning counterpoint. When a woman asked “Why do I love your music?”, Glass abruptly responded “What do you care?” In a way, he had already given her the answer, but it might not have been the one she was looking for. Far from a thesis on the importance of repetition to the human psyche his answer was (in my paraphrase): “Because I studied under Nadia Boulanger and Ravi Shankar, and because I studied counterpoint for two to three hours a day for three years.” While Glass took comfort in yarns about Shankar and India, those who sought comfort in Glass would have been disappointed, both in interview and performance.

If, as Brian Ritchie told Gail Priest (RT100), “music is the comfort food of the arts,” then the audience was out to gorge itself on Glass’ performance of his own solo piano works at Federation Hall. His expressive rubato (speeding up and slowing down) was a welcome departure from others’ metronomic interpretations of his works, though his faltering polyrhythms and fudged passages often snapped listeners out of their contemplative reveries. Observing that “not much has changed” since its composition, Glass concluded with a moving performance of the anti-war poem “Wichita Vortex Sutra,” accompanying a recording of the poem read by its author Allen Ginsberg. Indicative of Glass’ performance as a whole, “Wichita Vortex Sutra” did not strike me so much as a rousing call for peace as a dejected ode to the past.

inspiring exploration

Back at Princes Wharf the paroxysms of art-joy continued. Fabio Bonelli (aka Musica Da Cucina) painted a musical image of his two aunts living in Sondrio—a town in Italy that doesn’t see the sun for several months a year—using funnels, cups of water, silver forks and a clarinet. Pateras/Baxter/Brown barraged the audience with their prepared instrument sagas. Owen Pallett deftly manipulated violin loops to create clever, Mozartian, episodic pop miniatures. Amanda Palmer sang about her map of Tasmania. South Australia’s The New Pollutants performed a chilling live score to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis with vocalist Astrid Pill and cellist Zoë Barry. Neil Gaiman read a story with live accompaniment by FourPlay, and audiences queued for hours to see BalletLab’s trio of dance works. By inspiring the audience’s exploration of new musical experiences, not demanding it, MONA FOMA hit its mark.

MONA FOMA – Museum of Old and New Art Festival of Music and Art, curator Brian Ritchie, MONA, Hobart, Jan 14-20; www.mona.net.au

This article was originally published online March 7, 2011

RealTime issue #102 April-May 2011 pg. 5