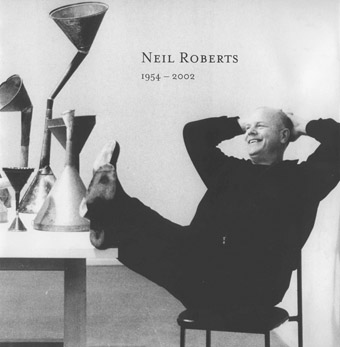

Obituary: Neil Roberts

Deborah Clark

Neil Roberts was a wonderful artist. He made works that were imaginative, challenging, playful, and always thoughtful. His art is lyrical and elegant, but in its spare beauty there is strength and integrity. All those qualities of his art were so absolutely present in Neil’s life, and in the way that he related to the world and to all of us. He was a wonderful artist because of that—he was true to himself in his art making. And he was a wonderful artist because he saw himself as part of a community of artists, and because he made us see ourselves that way too.

Neil Roberts was a wonderful artist. He made works that were imaginative, challenging, playful, and always thoughtful. His art is lyrical and elegant, but in its spare beauty there is strength and integrity. All those qualities of his art were so absolutely present in Neil’s life, and in the way that he related to the world and to all of us. He was a wonderful artist because of that—he was true to himself in his art making. And he was a wonderful artist because he saw himself as part of a community of artists, and because he made us see ourselves that way too.

Neil came to the Canberra region nearly 20 years ago, in 1983. How lucky we are to have had him here for so long. Klaus Moje, the inaugural Head of the Glass Workshop at the Canberra School of Art, invited Neil to join him in a program of innovative, adventurous teaching in the workshop, and in his two years at the School, Neil had a profound effect on his colleagues and his students. Though he subsequently chose the sometimes precarious life of an independent artist, he always had a strong commitment to teaching and was an important mentor to countless artists, many of whom are here today. Neil had been trained as a glass blower at the Jam Factory in Adelaide and then at the Orrefors Glass School in Sweden and the Experimental Glass workshop in New York. His practice shifted over time from that of an artist who worked in glass to a sculptor whose practice describes a kind of unfolding, a cycle of collecting and reflecting, forming bonds between objects, between objects and language; re-making, re-thinking, taking chances.

When Neil and eX de Medici turned the old glass factory in Uriarra Road, Queanbeyan into a studio, home and the sometime gallery Galerie Constantinople in the late 1980s, it became a focus for exciting and idiosyncratic art and for the huge network of friends and colleagues who lived in the region or visited from interstate and overseas. A visit to the factory was always a treat, whether it was a performance night, the opening of one of those fugitive 3-day exhibitions, a special party for a friend, or just a lazy afternoon with cups of tea in the sun. Neil’s working space tells so much about him—his love of ordinary objects, his sense of order, his respect for tools, for objecthood, for the thingness of things. In the last few years the space was transformed, and the zone of comfort that he and Barbara Campbell created there seemed like a natural evolution from his space to their space.

As well as the richness of his life and work at home, Neil was an artist out in the world. He keenly sought knowledge, adventure, and exchange with colleagues in Australia and overseas. His many rewarding professional experiences included artist’s residencies at the Australia Council Greene Street studio in New York, Art Lab in Manila, and the University of South Australia Art Museum. Neil loved and thrived on his engagement with artists, writers, curators, academics and any other curious people and his experiences with them, and with their work, were distilled into his thoughtful, beautiful art. A Filipino friend said about the work Neil made in response to his time in Manila that, “maybe it takes an outsider to realise the treasures inside ourselves”.

Everyone here, and others mourning elsewhere, has a special relationship with some particular work of Neil’s. For me, at ARX in 1989, when I saw Neil’s brilliant neon words ‘Tenderly, gently’ writ against the Perth skyline of the butch Bond tower and the corporate madness of the times, I knew I was seeing something special. It was an exquisite and poignant work of art. In a very real sense his work was always about masculinity: its culture, its rituals, its nonsense, and the fantastic possibilities of its transformation.

Neil’s art had that kind of arresting impact on many people. Flood Plane, his commissioned work for Floriade in 1990—an irrigation machine on Nerang Pool, strung with neon words from an Adam Lindsay Gordon poem, was breathtaking. And his work for the Canberra Playhouse, with its delicious play on words, is a constant source of delight for city strollers. Neil was enormously respected and valued in his adopted town and region, and he was the inaugural recipient of the ACT Creative Arts Fellowship in 1995, and the Capital Arts Patrons Organisation Fellow in 2000. Neil’s survey show last year at the School of Art, The Collected Works of Neil Roberts, elegantly curated by Merryn Gates, re-assembled some of his most poetic works; works which resonated with the gentle wit of Robert Klippel, and the formal grace of Rosalie Gascoigne, both artists he admired enormously. The Collected Works were about found, and lost, objects—in these, as in everything he did, Neil looked for the human traces in things, the fragments which reveal things to us, the unseen possibilities in history and in our own stories.

Many people have treasured objects given to them by Neil—postcards, toys, badges, photographs, rolling pins, words, and letters, and will forever treasure the dialogue they had with him over years. His genuine curiosity, attentiveness and compassion made him a unique friend. My son Frazer, when confronted with the awful reality of Neil’s death said “I didn’t think it would happen to someone I know, who carried me on his shoulders”. That feeling of disbelief has been echoed across the broad community to which Neil belonged—he carried many of us on his shoulders, lightly and cheerfully; he gave us huge support, in times of grief, and in times of hope. He valued people and he loved his friends, and we valued him and loved him too—an exceptional, stimulating and inspirational artist, and a lovely, gentle smiling presence.

And we had reckoned on him growing old, and always being there, carrying us on his broad shoulders.

Neil Roberts died accidentally on March 21, 2002. This eulogy was delivered at his funeral. Deborah Clark is the Editor of Art Monthly.

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 12