on the dyingness of things

jana perkovic: melbourne international arts festival

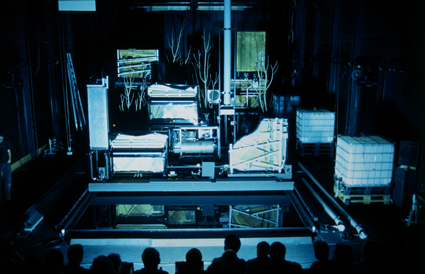

Stifters Ding

photo Mario Del Curto

Stifters Ding

WHAT IS A ROSE BEFORE IT HAS A NAME? WHAT IF OUR ABILITY TO INTERPRET AND INTERVENE, OUR AGENCY TO DECIDE WHAT THINGS ARE, RECEDED AND WE COULD SEE THE WORLD WITHOUT ADJECTIVES, UNMEDIATED BY INTENTION? TO WHAT EXTENT ARE WE MADE IN TURN BY THE WORLD WE THUS CREATE? AND WHAT IS THE AGENCY OF THINGS? BETWEEN CARNIVAL OF MYSTERIES, HOTEL PRO FORMA, HEINER GOEBBELS’ STIFTERS DINGE, DAVID CHESWORTH’S RICHTER/MEINHOF-OPERA, SOME VAST GROUND ON THE TOPICS OF SYMBOLISATION AND REPRESENTATION WAS COVERED. IT SOUNDS PREPOSTEROUS; BUT THIS IS HOW.

richter/meinhof-opera

David Chesworth’s Richter/Meinhof-Opera was a highly anticipated take on the Red Army Faction’s Ulrike Meinhof. Announced as a 45-minute, pocket performance artwork (opera it wasn’t), it was an even shorter, quieter beast than expected. Tackling a potentially inexhaustible subject with an absolute minimalism of input and effect, it treads that usual fine line between the open-ended and the non-committal. It barely skims the complex story of Meinhof, respected journalist who joined a terrorist organisation, and whose simultaneous canonisation as left-wing martyr and demonization as Communist murderer still divides Germany. The only trace of the other members of the RAF is a record player, playing an Eric Clapton track, exactly as it did when Baader committed suicide in his prison cell. This is a rare instance in which the music goes beyond atmospheric soundscape; the other is a string duet, which mellifluously contrasts with the rest of the work, enhancing its thinness somehow. A few of Meinhof’s best-known quotations are projected onto ACCA’s shard-like walls, while centre-stage stands Gerhard Richter (Hugo Race), who famously painted RAF members’ death portraits in 1988, and was accused of mythologising terrorism.

The intended core of this work is the enormous disjuncture between direct action, advocated by Meinhof (often paraphrasing Brecht), and the indirectness and detachment of representational art, which often gives life to such ideas. The inability of our own cynical, ideologically unconvinced contemporary era to present the full spectrum of Meinhof’s time is another big theme. However, to say that Richter/Meinhof-Opera ‘explores’ them would be to give it excessive credit. Between Richter’s moody, detached canvases, the monochrome photos of the stylish Faction (which overwhelmingly comprised young women) and the occasional discursive duet (the libretto is a slim pastiche of quotations), the myth of RAF is presented as a matter of aestheticising or not; and the issue of direct action as a matter of professional ethics (to identify or not with one’s subject matter). Cold War politics lie forgotten, and ideas are not so much revealed as hinted at.

Even Richter, whose engagement with RAF is the focal interest of the opera, remains shorthand for the generic Artist. Evading all the big questions on this big topic, Richter/Meinhof-Opera feels and looks as if in development, like a sketch for a bigger work.

stifters dinge

Those who work with things (sculptors, architects, furniture makers) are often perplexed by the readiness with which more idealist disciplines (theatre, poetry) turn this material into signs and ideas. The result is frequently naive mystification, or embellishing fetishism: we have all seen signed urinals, soup cans, as well as their less rounded children—from derelict buildings employed as metaphors to artsy tapestries. What makes Heiner Goebbels’ Stifters Dinge so remarkable is that it does none of this, and has its audience enraptured. Its form is sui generis: a peopleless performance, or perhaps just a giant moving contraption. And yet, its workings are magical, for idealists and materialists alike.

Stifters Dinge’s dramaturgy is a sequence of apparently unrelated mechanical events: light changes, mechanical actions, sound clips and video projections. These are organised around a host of motifs: principally, the writings of Adalbert Stifter, a 19th century Austrian novelist whose prose is notoriously thickly furnished, upholstered, landscaped. (Literary lore has it that modernisation was already making advances into the order of things, and that 19th century naturalism was a kind of urgent stock taking.) Other motifs are the Renaissance dicovery of geometric perspective (chiefly Paolo Uccello’s paintings), utilitarian traditional music (Greek, Papuan, Colombian), voice recordings of Malcolm X. With technical perfection, the sequence of mechanical events coalesces into a world, all whilst remaining first and foremost mobile matter, without metaphors or superimposed meaning. The work builds into a deeply satisfying and meaningful totality by making us aware precisely of the bottomless materiality of its devices. When dry ice bubbles up in the three shallow water pools, seeing the trick does not stop the entire audience from holding their breath in awe. Stifters Dinge purges the stage of illusion and interpretation, but the ‘things’ that remain are neither threatening nor banal. Rather, they assume almost sacral fullness.

carnival of mysteries

Carnival of Mysteries, conversely, is an image of a carnival world. It has it all: tents, noise, nudity, candy floss, its own (inflated) currency and many short acts of varying skill and engagement. It is as entertaining and uneven as any carnival. It is also no more dramaturgically cohesive, nor exploratory: neither does it try to bring a superior level of artistry to the content, nor interrogate the form (in the vein of One-on-One Festival; RT99, p10). With many times more mini-shows than can be experienced in the allotted two hours, it is a somewhat frenzied experience, lacking the relaxed atmosphere of a fair. But the intensity does not translate into superb artistry, at least not in the fraction of the shows I witnessed. Should we be deconstructing it critically, suspending critical judgement, or witnessing it referentially? If Carnival is the answer, what is the artistic question? Is it a lowbrow event for a highbrow audience, with highbrow performers? Is it a replacement for Spiegeltent, which used to be the place at MIAF for circus, burlesque and other kinds of friendly lowbrow? A ‘carnival but of another kind,’ it is both too close, and once removed.

Tomorrow, In A Year, Hotel Pro Forma

photo Claudi Thyrrestrup

Tomorrow, In A Year, Hotel Pro Forma

tomorrow, in a year

Hotel Pro Forma’s Tomorrow, In a Year, an ‘electro opera’ about the life and work of Charles Darwin, was the most controversial show of this year’s MIAF (its response coming close to the outrage caused by Liza Lim’s The Navigator in 2008 (RT87, p8); opera is clearly fraught cultural ground in Melbourne). It is a conceptual work, with no plot to retell. It explores the thematic links between four moments in Darwin’s life—including the death of his daughter (potentially linked to his marriage to a first cousin)—and the implications of his theory . The endless mutability of the natural world, whose laws form us despite our pretended detachment, and whose laws we can never break, is the terrible heart of this work. It opens with potentially bewildering, undifferentiated stage sludge, an image of the original primordial soup of life; it ends as accelerating hydroponic chaos, or perhaps complex order?

The stage imagery is poor: only two planes of horizontal movement, no interaction between the performers, green laser beams and much dry ice. Using botanical drawings and video footage of water, Hiroaki Umeda’s algae-like choreography and the occasional verse about geological time and entombed carcasses, it explores a complete intangible: the fact that the material world is bigger than a human being, that we do not become through it, but are crushed by it.

But unlike Chesworth’s non-committal opera, it is fully exploratory. A note of the Romantic sublime runs through the work, unnoticed by those who bemoan its coldness. It unearths a potential Western counterpoint to the Japanese concept of ‘mono no aware’: the awareness of the dyingness of things, of the essential inability of matter to last. Just as cherry blossoms are less pretty than tragically transient, so is Tomorrow, In a Year not so much beautiful to watch as it is a despairing attempt to grasp cosmic complexity.

In the absence of meaningful stage action, enjoyment of this opera is strongly predicated on appreciating the music, by the Swedish electronic duo The Knife, which forms its narrative, emotional and intellectual core. It is a complex composition of natural and electronic noises, bel canto, house beats, borrowings from Purcell, early polyphony. And yet this collage of pop and found remains staunchly anti-metaphorical, a postmodernist pile of stuff asking to be understood literally: when Kristina Wahlin sings that “epochs collected here,” she is relating a geological fact, not a poetic truth.

While the work has been hailed as showing the future of the operatic form, it seems to succeed largely in musical terms. Visually, it attempts an abstract variation on a nature documentary, with results too reminiscent of late 1990s raves to be genuinely eligible for the label ‘innovation.’ Knowing that cyborgs, virtual reality and Dolly the Sheep were all the rage circa 1998 provides some dramaturgical solace, but does not compensate for Tomorrow, In A Year falling short of its promise.

2010 Melbourne International Arts Festival: Richter/Meinhof-Opera, direction, music, sound design David Chesworth, text David Chesworth (after Tony MacGregor), performers Kate Kendall, Hugo Race, lighting Travis Hodgson; ACCA, Oct 14-16; Stifters Dinge, concept, music, direction Heiner Goebbels; Malthouse, Oct 8-11; Carnival of Mysteries, creators, directors Moira Finucane, Jackie Smith, production design The Sisters Hayes; fortyfivedownstairs, Oct 6-30; Hotel Pro Forma, Tomorrow, In A Day, directors Kirsten Dehlholm, Ralf Richardt Strobech, music The Knife; Arts Centre, Melbourne, Oct 20-23

RealTime issue #100 Dec-Jan 2010 pg. 10