On the surface of memory and history

Matthew Clayfield, Miguel Gomes' Tabu

Tabu

With the hype that accompanied it long behind us, it seems fair to say today that Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist (2011) was little more than a parlour trick: a blatant retelling of Singin' in the Rain that convinced moviegoers it was original; a picture with wall-to-wall music and diegetic sound that convinced them it was silent. It was trickle-down formalism: the inevitable middlebrow stalagmite formed by the steady dripping over time of more ambitious and avant-garde films like Guy Maddin's Eisenstein-Lang mash-up, The Heart of the World (2000), and Steven Soderbergh's cold, airlessly note-perfect recreation of the Classic Hollywood Cinema in The Good German (2006).

Miguel Gomes' Tabu (2012) sits somewhere between Hazanavicius and his betters, but is nevertheless still a parlour trick. Without necessarily meaning to, it makes history disappear, and it is for this reason that it is both a much more interesting and much more problematic film than the Oscar winner that preceded it.

The film is broken up into two parts of roughly equal length. It opens with a prologue: a 1920s silent film about a heartbroken adventurer who, haunted by his dead lover, seeks refuge in the wilds of Africa. The film is being watched by Pilar (Teresa Madruga), a lonely middle-aged woman living in contemporary Lisbon. Pilar's loneliness is as acute as Rui Poças's photography is dismal and grey: her only contact is with an overeager suitor who falls asleep at the movies (Manuel Mesquita); her confused and aging neighbour, Aurora (Laura Soveral); and Aurora's Cape Verdean maid, Santa (Isabel Cardoso).

Tabu

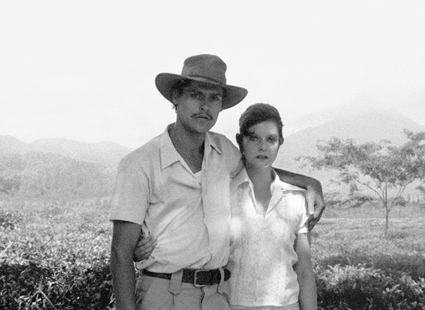

Aurora grows ill and asks Pilar to track down one of her former lovers. Pilar does, but is too late: Ventura (Henrique Espírito Santo) never gets to reunite with the love of his life. And so the second part begins: Ventura tells Pilar and Santa the story of his doomed affair with Aurora (Ana Moreira) in an unnamed African colony years earlier. From austerity-hit Lisbon to the sun-drenched foothills of the fictional Mount Tabu, it's Out of Africa or The Short, Happy Life of Francis Macomber meets a Douglas Fairbanks romance-adventure, and while both parts of the film are shot in black-and-white the entire palette suddenly changes.

Like The Good German or Pablo Berger's silent bullfighting fairy-tale, Blancanieves (2012), The Artist was marked by an essential parallelism between its form and the setting of its narrative. Tabu's second part takes a different, rather more ambitious route. There is a distinct gap between the place and period Ventura is recalling—Portuguese Africa at the beginning of the 1960s—and the much older style in which it is being rendered. What's more, unlike Soderbergh's or Berger's, Gomes' rendering is intentionally unfastidious. Yes, when the characters move their mouths to speak, we hear no dialogue. But rather than The Artist or Blancanieve's title cards we get Ventura's style-inappropriate voiceover. Then when the characters open their mouths to sing—early doo-wop tunes, mostly—their lips and the lyrics are perfectly synched. So what is going on here?

The most likely explanation is that Tabu's second part is not the filmmaker's cinematic fetish object—or, at least, not completely—but rather to a significant extent Pilar's. It is a product of an imagination highly but imperfectly influenced by cinema: as in a dream, the films Pilar turns to escape her humdrum existence influence how she imagines Ventura's story.

While this reading might go some way towards explaining why the film seems reluctant to deal with questions about colonialism and its legacy—because they fall outside of the character's frame of reference—it need not go any way towards justifying it. In a European art cinema landscape that has grappled mightily with these questions—think Herzog, Denis, Haneke and the Dardennes, just to name a few—a film that approaches them with purely aesthetic answers is to be viewed with some degree of suspicion.

Tabu

Indeed, as idealised by Pilar and aestheticised by Gomes, Aurora's past can't help but come across as somehow preferable to the dreary present, even as black women serve lemonade on the patio and black men move the ping pong table that the white men have left out in the rain. If these glimpses of servitude are intended to come across as somehow damning, they fail to without a lot of heavy lifting from the viewer who must constantly struggle against the niggling feeling that the film is somehow longing for the colonial period. Yes, the appearance of these servants retrospectively situates Santa's life in Lisbon on a spectrum of experience that covers both the colonial and post-colonial periods. But these are hardly the Greek chorus of blue-collar cleaners that populate Sally Potter's Yes (2004), those unseen but all-seeing reminders of the system of oppression that allows these imperial follies to take place. They are, rather, akin to scenery.

What is being explored here, first and foremost, is a romance between two privileged whites: colonial Africa is a setting like any other, seismic events potential plot points, history a mere surface. Along with films like Claire Denis' White Material (2009), I occasionally found myself comparing Tabu unfavourably to Quentin Tarantino's Inglorious Basterds (2009) and Django Unchained (2012). Tarantino shares Gomes' impulse towards homage and bricolage, but to degrees of success that are open to debate, also seeks to channel that impulse towards at least some kind of historical inquiry. Tarantino may be the least theoretical, least philosophical filmmaker working today, but he nevertheless uses his ultra-cinematic style to place certain problems front and centre. Tabu, in striking contrast to this, uses its style to brush such problems aside.

Tabu, director Miguel Gomes, distributor Palace Films; http://www.palacecinemas.com.au/movies/tabu/

See also Philip Brophy’s take on Tarantino’s soundtracking of Django Unchained in RT114’s Audiovision

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg. web