Opening the cage door

Josephine Wilson

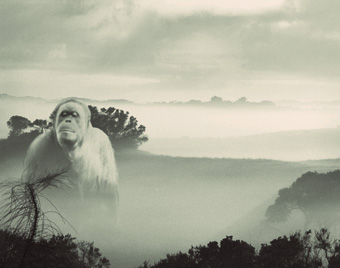

Lisa Roet, Pri-mates

Once upon a time Tony Bennett coined the term ‘exhibitionary complex’ to characterise the institutional shift of objects and bodies from the purview of the sovereign prince or lord into the public gaze. According to Bennett (following Foucault), the emergent 18th and 19th century museums and galleries performed the function of allowing people, “en masse, rather than individually, to know rather than be known; to be the subjects rather than the object of power; interiorising its gaze as a principle of self-surveillance, hence self-regulation.” One of the things we learn from our galleries, museums and zoos is nothing less than the order of things, ourselves included.

Don’t get depressed. Things can change. Take zoos: nowadays we construct simulated rain forests for the gorillas, a savanna for the African beasts, rocky pools for the turtles. We ask that our zoos in some way resemble the imaginary origins of our captive species (never mind most have never seen these far-away first homes). We tolerate enclosure as long as the frame is obscured, blended, masked by fake boulders and clumping bamboo. We continue to travel through gates and doors to see our wild things, but we can no longer ignore the subjectivity of our objects; hence, we tolerate the odd glimpse of the meerkat and suppress our frustration at animal-centred timetables (What? The tiger is sleeping again?).

But what about the gallery? Is it still a concrete cage for art and its objects?

Such questions arose as I traversed the exemplary space of the Lawrence Wilson Gallery in search of Lisa Roet’s exhibition Pri-mates, fantasising, like a latter-day Jane Goodall or Dianne Fossey, an encounter. Is there anything more tremulous, poignant, more poetic and dramatic, more beloved of Hollywood anthropology? It appears that our imagination—damp domesticated cliché that it is—still requires pockets of virgin forest and impenetrable wilderness, where we can meet the unseen and the unknown. The essence of ‘the encounter’ is that it be unexpected and in many ways unrepeatable. Though increasingly rare (I hesitate to say endangered) art can be such an encounter, as when, at a young age I saw the Bridget Riley exhibition at the Art Gallery of Western Australia: you mean, that’s what art looks like?

When it comes to encounters with the Other, we try to be alert to the fluidity of boundaries, the violent history of frontiers, and we prefer to use words like dialogue and exchange. And if we are not yet vegetarian, we are definitely thinking about it.

At the doors of Lawrence Wilson I am greeted by a video monitor showing an image of a human hand reaching through a cage bar towards an ape’s hand (or is it a monkey?). The reference is obvious. I am annoyed. I want an encounter, not an art-historical moment; I want a disturbance at the edge of the frame, a fracas, a disordering of subject and object, not an easy key to reading the work.

I pick up a sheet at the desk and read; “Pri-mates deals with investigations into the genetic similarities that exist between humans and primates, issues of language and communication and the point at which humankind is both alienated from and joined to the animal kingdom.”

Roet is fascinated by primates. Fascination is dialogic; to ‘fascinate’ is to ‘cast a spell over by a look.’ Her process is exemplary; residencies in zoos, visits to Borneo, long periods of study, interaction and engagement.

I linger at the works on paper—the feet and hands of chimpanzees. There is an essay here: on monkeys, mimicry, finger-puppets mark-making, creativity, but I am not equipped to write it. Perhaps Roet’s attraction to charcoal lies in the fantasy of recuperating primal creative drives (the child learning to grasp and strike the paper, the history of mark-making in art.) The huge drawings of fingers/toes are at once grotesque and beautiful. They conjure the whole history of things; the bleak scientific study of the fragmented ‘primitive body’, the anthropological and scientific scalpel cutting and bottling and labelling, the gaze of the student studying classical form (the hand of David). I move on. The bronze casts of chimpanzee’s heads recall photographic studies of babies attempting verbal communication. These works fascinate me. They are profoundly ambivalent; at once a study of a nameless other whose individual subjectivity has been subsumed in the name of genus and species, and an indictment of the anthropocentric limits of post-human portraiture.

Will there ever, I wonder, be an ape in the Archibald?

In Kate McMillan’s Disaster Narratives there is no fantasy of mutual recognition. Vision is not privileged in this exhibition, because on one level there is nothing to see. Superficially epic and classical in its aesthetic, Disaster Narratives draws attention to the ways we have encountered the art frame, and the potential emptiness of that encounter if the surface image or content is the organising or dominating principle. The huge central photographic image conjures a particular painting (Dejeuner sur l’herbe), but it also references the enormous history paintings found in some museums. The shell wedged high up in the wall exemplifies the exotica illuminated in a table case in a natural history exhibit. Yet the huge photographic image is also wallpaper—a billboard, and the single shell excised from taxonomic security is surely a private mnemonic, a reminder that outside of the cage, the images roam free. Hence the small static video image is both avant-garde and banal; on the one hand a refusal to reward the viewer with a ‘feed’, on the other an invocation of the endless tedium of domestic television. The ominous interiority of the large video projections of tunnels belongs just as well to a contemporary art space as to a late-night offering of Hollywood gothic-horror.

So what is the real story here? Who would know? A local viewer might confirm that the distant island in the video is Rottnest, formerly a prison for Aborigines, now a holiday destination. A well-travelled member of the audience might recognize the photographic wallpaper as Rubble Hill, a park built upon the destruction of Berlin. Someone else might know that Mao secretly built tunnels beneath Beijing, just in case of an emergency. In its very inability to narrate, this work enacts ‘the disaster’, which in Blanchot’s writings is that which is outside of the human, that which by being outside cannot be represented.

Meaning here lies beneath the surface, but it cannot be exhumed. Postmodernism eschews depth, yet this work is not about mere juxtaposition. It is not playing with us. The tone is serious. Mournful. Disaster Narratives reads like a very private, very formal essay on grief and mourning written through the formal hieroglyphics of art history. A disaster takes the subject to the edge of experience and abandons them there. Rather than being wilfully obscure, ironic, or “leaflet-dependent”, as one reviewer put it, I think of this work as leading the animal right to the door of the cage and opening it. Where, upon looking out, the terrified animal realises it is incapable of crossing the threshold.

Perth International Arts Festival: Lisa Roet, Pri-mates, Lawrence Wilson Gallery, University of Western Australia, Feb 13-April 20; Kate McMillan, Disaster Narratives, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, Feb 12-March 21

RealTime issue #60 April-May 2004 pg. 37