othering the cultural mainstream

mike walsh: 2008 vancouver international film festival

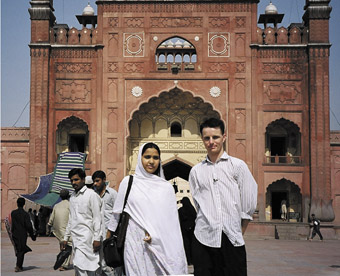

Donkey in Lahore

THE VANCOUVER INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL (VIFF) IS A PERFECT EXAMPLE OF THE WAY THAT FESTIVALS PERFORM TWO OPPOSITE FUNCTIONS: THEY ALLOW PEOPLE TO SATISFY THEIR CURIOSITY ABOUT THE FOREIGN AND THE UNFAMILIAR, WHILE ON THE OTHER HAND, THEY CAN ALSO BE INTENSELY LOCAL AND PAROCHIAL. THIS TRANSLATES TO TWO MAIN PROGRAMMING STRANDS. THE DRAGONS AND TIGERS SECTION ON NEW ASIAN CINEMA HAS BEEN RUNNING FOR 15 OF THE FESTIVAL’S 27 YEARS. IT GIVES VIFF ITS INTERNATIONAL REPUTATION, AND THIS YEAR DREW REPRESENTATIVES FROM MOST OF AUSTRALIA’S FILM FESTIVALS. IN THE SECOND WEEK OF THE FESTIVAL, THIS STRAND GIVES WAY TO THE CANADIAN IMAGES FOCUS, WHERE NATIONALISM IS PAID ITS DUES.

Given Canada’s status as a Commonwealth country whose nationalist impulses are generally constructed through finding ways to distance themselves from the overpowering presence of the United States, there are grounds for considering analogies between Australian and Canadian film production. This is no new idea, dating back to the influence of John Grierson in founding the National Film Board of Canada and providing the conceptual basis for documentary production in Australia.

When Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka wrote their history of the Australian film renaissance at the end of the 1980s [The Screening of Australia, Vol 2: Anatomy of a National Cinema, Currency Press, Sydney, 1988], they referred disparagingly to the possibility that the Australian cinema might become prone to “Canadianisation”, that is, it might become a place overtaken by Hollywood production. Closer to the present day we have the meagre domestic box office of both industries and similar government responses divided between location subsidies to attract Hollywood (we should be so lucky as to be Canadianised!) and tax credits to encourage the locals.

The films shown at VIFF this year encourage a further analogy between Australia and Canada based on a growing interest in the othering of the cultural mainstream.

deepa mehta’s heaven on earth

It was significant that directors whose reputations are tied to their cultural otherness made the most prominent Canadian films at Vancouver this year. Deepa Mehta (Earth, Water, Fire) is an Indian-born Canadian resident who makes most international middle-class viewers’ favourite Indian films. While she has moved her production activities back and forth between Canada and India, Mehta has constantly foregrounded the ways in which Indian cultures victimise women.

Her new film Heaven on Earth (you ought to be able to guess that the title is ironic) is no exception. Bollywood star Preity Zinta plays the decidedly anti-glamorous role of a battered wife in a Canadian-Indian family. There’s not a lot in the film to surprise you with the familiar narrative arc of (1) woman as victim, and then (2) victim finds her inner strength. One of the more interesting things about the film is how matriarchal families produce and reinforce positions of oppression for women. Chand, the protagonist, finds her strength to resist from the inspirational story given to her by her mother, but Rocky the brutish husband is a mummy’s boy who beats his wife with his mother’s consent and tacit encouragement.

While India is heat and colour, Canada is cold and blue. The power of the matriarchy is the constant between the two, suggesting that power over sons is a very different thing from power over daughters. Mehta suggests that maternal power over sons breeds a resentment, which finds its outlet wherever it can—and usually this means spouses.

atom egoyan’s adoration

Atom Egoyan (Exotica, The Sweet Hereafter) is perhaps Canada’s best known art cinema director given that he has never been tempted into genre filmmaking and enticed south of the border like David Cronenberg. Critics have made much of Egoyan’s Armenian-Egyptian background, though he has lived nearly all of his life in Canada. His new film Adoration returns him to familiar territory where a slowly tracking camera moves constantly across the surface of a brooding landscape. Conversations always appear pregnant with meaning as every utterance gestures towards something more.

A schoolboy creates an online sensation by revealing his father’s terrorist attempt to blow up an airliner. Things are rarely what they seem however, and terrorism becomes a symbol for more intimate forms of dysfunction. Egoyan’s narratives (think of The Sweet Hereafter) often work through reference to some primal trauma, and this is no exception. For Egoyan’s characters, the present is generally a way of working back to the past. His films are the fictions of inwardness and, for them to be effective you need to find the right wavelength for encountering their specific form of stylisation.

There is a lot of blather in the film about online discussion of morality, about the lack of an imaginative understanding of the sufferings of people from Middle Eastern cultures, but the terrorism that Egoyan sees as the model for all trauma and revolt is that inflicted within families. At this level, perhaps his film enters into a conversation with that of Deepa Mehta.

So what’s the bridge back to my analogy between Canadian and Australian filmmaking? For all of the rhetoric of cultural nationalism, all of the Daryl Kerrigans and Crocodile Dundees, of telling our own stories, the most fruitful strand of Australian cinema comes from the engagement of Australia and distinctly separate cultures. I’m thinking here of the tradition of Film Australia docos in Papua New Guinea, the South Pacific and Asia.

australia & other people’s stories

The contemporary inheritors of this tradition can be found in the work of George Gittoes in the Middle East, or in recent films such as Benjamin Gilmour’s Son of a Lion made in Pakistan. The Australia represented by (if not in) these films is not the inward looking one conjured up by the rhetoric of a nationalism obsessed with its own stories. Rather it is the Australia that has finally started to look outward at its region, to insist that Australia must engage with the people of the Middle East on a personal basis and not just through superpower politics.

The case in point at VIFF was Faramarz K-Rahber’s documentary Donkey in Lahore. The Australian-Iranian documentarist, who is based at Griffith University, follows a Queensland goth puppeteer in his unlikely pursuit of Amber, a young Pakistani girl with whom he fell in love during a brief stay in Lahore. Brian (or Aamir as he renames himself after his conversion to Islam) is an unlikely hero but clearly a romantic in every sense of the term. He takes in his stride the repeated kicks in the head the world delivers to him, reasoning that sooner or later, it is only reasonable that brute reality will have to lie down in the face of his ambitions.

The most interesting thing about the film is the way K-Rahber starts to function as a go-between for Brian/Aamir in Pakistan and an interpreter of his actions for viewers of the film. The film neatly reverses the cultural politics of much traditional anthropological filmmaking where Anglo-Australian filmmakers occupy a high ground of knowledge and truth, explaining the quaint ways of the natives.

Donkey in Lahore gained additional stature from the comparison with The Convert, a Thai film in the Dragons and Tigers section. This documentary also tells the story of a woman who converts to Islam in order to marry. The problem here is that the filmmakers simply don’t have much that is very interesting at which to point the camera. This is a problem compounded by the fact that the couple who are the subject of the film obviously participate in the shooting of it. Rather than the growth of a productive (if potentially painful and embarrassing) relationship between filmmaker and subject, there is a closeness here which seems to preclude insight, as if you don’t want to pry too closely into the troubles of someone close to you.

So, maybe this is the conclusion to bring away from Vancouver: to praise not the telling of our own stories, but the curiosity to stick our noses into the stories of those who are different from us.

Vancouver International Film Festival, Vancouver, Sept 25-Oct 10, www.viff.org

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg. 18