outside the western box

danni zuvela: the view from elsewhere, GoMA

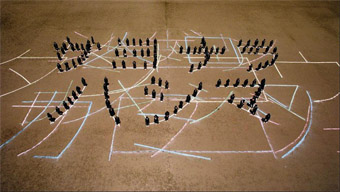

Spelling Dystopia 2009, Nina Fischer & Maroan El Sani

© the artists

Spelling Dystopia 2009, Nina Fischer & Maroan El Sani

Downstairs, in the dark of the Gallery of Modern Art’s black box Cinema B, a bevy of gorgeous, entirely naked Eurasian women cavort with a flock of bemused sheep in the stony Kazakhstani countryside. These slender beauties gleefully gorge on a roasted sheep’s head, starting with the molten eyes and then, flinging their waist-length black tresses with ecstatic abandon, writhe erotically with the animals amidst the straw, pee and liquid shit of a sheep-pen.

Set to a thumping ethno-electronic soundtrack, Almagul Menlibayeva’s sensual, telluric video Headcharge (2007) is as mesmerizing as it is perplexing. As Kathryn Weir cautions in her catalogue essay for The view from elsewhere, GoMA’s program of moving image art from Asia and the Middle East, the temptation for those schooled in Western avant-garde art traditions is to try to read this artwork in the transgressive tradition of the Viennese Aktionists, whose experiments, as Stephen Barber notes, “disassembled the human body and its acts into compacted gestures of blood…and meat.” However, as Weir goes on to note, beyond surface similarities of public nudity, freeform sexuality and “abject smears”, to place Menlibayeva’s highly specific video practice in this Western tradition is as much a misreading of the work as the other common responses—”exoticising fascination or complete misunderstanding”—to the art of ‘elsewhere’ explored in this extensive, challenging show.

Complex art such as Menlibayeva’s “Romantic punk shamanism”, which synthesises Central Asian and European references—specifically Kazakhstani cultural iconography with distinctly Western countercultural, psychedelic and Baroque flourishes—poses a unique challenge. The double gesture of familiarity and difference in this kind of work requires a viewer capable of stillness, observation, and “cultivating an openness to what is not known or cannot be known.”

The view from elsewhere offered Brisbane audiences a unique opportunity to cultivate that openness through the installed white cube show, Small acts, and the black box cinema program in which Menlibayeva’s dynamic videos were shown alongside realist documentaries and poetic short films from across the region. In Thai auteur Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s typically languid Primitive: A Letter to Uncle Boonmee (2009), a contemplative, searching camera rakes over the interiors of various wooden houses in a near-deserted village. Young soldiers dig up the ground outside one dwelling as the voices of three young men are heard repeating a letter to a man named Boonmee, about a tragedy in a small community, Nabua, which forced residents to flee their homes in panic. As a fearsome tropical wind seizes palms and banana trees and whips them into a wild frenzy, a swarm of bugs invades. Then the sky darkens, the camera tilts slowly to reveal a tracery of tree branches, and the bugs disperse. Weerasethakul’s earlier film, Like the Relentless Fury of the Pounding Waves (1996), shown with Primitive on the final Sunday of the program subtly explores four lives connected by a radio play, a “mysterious comedy and tragic drama!”, about the sea goddess Mae Ya Nang. As with countrywoman Sasithorn Ariyavicha’s meandering, reflective works (My First Film, 1991; Drifter, 1993; and Birth of the Seanema, 2004), this work is emblematic of the “dual consciousness” Mark Nash writes about in his catalogue essay, which sees international artists drawing on and developing aesthetic codes both culturally specific to Thailand, as well as histories of North American and European avant-garde and art cinema.

Cut Piece 2003, Yoko Ono

photo by Ken McKay © Yoko Ono

Cut Piece 2003, Yoko Ono

As the curators point out, video and performance art emerged roughly coincidentally, and the Small acts show makes explicit the links between historic performance art captured on early video and contemporary trends in video art, in which performance documentation features heavily. Nam June Paik’s pioneering Hands and Face (1961), featuring the artist passing his hands over his face in a kind of trance, frames the entry to the media gallery in which Small acts is housed. The viewer is then greeted with an installation of Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964, restaged 1996). In this seminal piece, Ono sits impassively as spectators are invited to cut pieces of her clothing away; while it’s hard not to notice the way male participants are quick to refashion her a décolleté (both in the early version and the later re-staging), the video also powerfully brings together other notions of sadism/masochism, desire/exhibitionism, and reciprocity in the art exchange.

In the next room, Kimsooja’s videos, A Beggar Woman, Lagos (2001) and A Homeless Woman, Cairo (2001) feature the artist adopting the forlorn poses of society’s most vulnerable members. With her back to the audience, lying or sitting begging in a public street, Kimsooja recalls the public struggles of non-violent activists, foregrounding her body as a political object and using video as witness. The majority of works in Small acts, however, reflect the easy availability of user-friendly, cost-effective digital technology and the way early video art’s political imperatives have given way, in a large part, to smaller aims constellated around self-expression. Of the documentation of simple performance gestures, particularly memorable are the sweetly domestic games of Guy Ben-Ner, and Taiyo Kimura’s absurdist acts, as they recall early cinema’s climate of wonder and discovery, and the period before genres such as ‘documentary’—or even ‘the trick film’—had fully crystallised.

Moby Dick 2000, Guy Ben-ner

© the artist

Moby Dick 2000, Guy Ben-ner

The documentary urge, discussed at length in the catalogue essays, defines both Small acts and the cinema program of The view from elsewhere. The show offers an opportunity to explore the outermost contours of documentary form, such as in Lida Abdul’s beautiful, unexpectedly ludic In Transit, where a rusting military airplane is joyously transformed into a plaything by a group of children; the haunting found-footage explorations of Ayisha Abraham and Yoo Soon-mi; and Kyrgyzstani artist Shaarbek Amunkul’s potent ethnographic studies. Legendary filmmaker Amos Gitai’s ‘archaeological’ exploration of a single street in West Jerusalem, in Bait (House, 1980), and News from Home/News From House (2005), which centres on the displacement of a Palestinian family, the appropriation of their property, and subsequent ‘lives’ of the house, is also a lesson in the power of non-fiction film.

In the light of so much pro-filmic reality, more constructed works such as Menlibayeva’s, Mona Hatoum’s exquisite Measures of Distance (1988), and Nina Fischer and Maroan El Sani’s study of Japan’s infamous uninhabited Gunkanjima (Battleship Island) Spelling Dystopia (2009), are a breath of fresh air. In particular, Inoue Tsuki’s remarkable A Woman Who is Beating the Earth (2007), about the hard rock fantasies of a woman struggling with an abusive relationship, stands out from the rest for its bravery, wit and raw poetic force.

The view from elsewhere was an expansive exhibition, involving numerous works and requiring multiple visits. It highlighted the unique ability of the relationship between the Gallery of Modern Art and the Australian Cinémathèque to articulate, with sensitivity and scope, the dimensions of contemporary moving image practice and how, in both gallery and cinema setting, the elsewhere of the title, in Mark Nash’s words, “is not just the elsewhere of the artist’s location, but that space which opens up within the viewer when they engage with the individual works.”

Small acts, curator Kathryn Weir, Media Gallery, GoMA, July 25-15 Nov 15; The view from elsewhere, curator Kathryn Weir, Australian Cinémathèque, GoMA, Brisbane, Oct 7–Nov 15

RealTime issue #93 Oct-Nov 2009 pg.