OzAsia Festival 2018: Beyond borders

Partway through my interview with Joseph Mitchell, now overseeing his fourth OzAsia Festival as Artistic Director, I observe that more and more dance, theatre and cross-artform work from Asia is being programmed by Australian festivals and flagship companies, often off the back of seasons at OzAsia. He seems genuinely pleased. “I’m glad you noticed that, Ben,” he says in his briskly efficient but always impassioned manner, “I really appreciate it.”

Since Mitchell took over from Jacinta Thompson as OzAsia Artistic Director in 2015, the landscape for Asian performance in Australia has undergone significant change. Before OzAsia, the only major celebration in Australia of Asian art was Brisbane’s Asia-Pacific Triennial, commenced in 1993 and principally a large-scale visual art exhibition but also including cultural performance and performance art. Commencing in 2007 and once the country’s sole festival focused principally on Asian performance, OzAsia now rubs shoulders with Melbourne’s Asia TOPA Triennial of Performing Arts, first staged in 2017, and, in Sydney, Performance Space’s annual Liveworks Festival. Meanwhile, organisations such as Contemporary Asian Australian Performance (CAAP, formerly Performance 4a) and Playwriting Australia, through its multi-year Lotus initiative, are fostering a new generation of Asian-Australian artists like Michelle Law and Katrina Irawati Graham.

This year’s OzAsia will be held a month later than usual but there’s an early program announcement to whet the appetite: three Australian premieres in dance, theatre and opera spanning South Korea, Japan and China, plus two major contemporary art exhibitions at the Adelaide Festival Centre and Art Gallery of South Australia. For the first time, the festival will also host the Jaipur Literature Festival, a South-Asian institution and purportedly the largest free literary festival in the world. The works announced so far attest to Mitchell’s adventurous programming and commitment to representing the formal and conceptual breadth of contemporary Asian performance. He explains that, unlike in previous years in which a geographical focus shaped his programming decisions, 2018’s festival has been more broadly conceived to showcase the global influence of Asia and its diasporas.

“In my first festival,” Mitchell tells me, “we had a country focus on Indonesia but for the last two I’ve tried to veer away from specific identities because I really think our message is solely that we’re a festival celebrating contemporary arts from across Asia. So this year our program, which we’ll release in about four weeks, is very broad. We’ve got work from East Asia, South Asia, South-East Asia and across the Middle East and the Arab world as well. So we’re looking at a broad continental perspective as well as works that are borderless or come from other regions of the world but that are driven or inspired by, or in some way taking consideration of, the impact of contemporary Asian art.”

Eun-Me Ahn, Dancing Grandmothers

I begin by asking Mitchell about Dancing Grandmothers by prolific South Korean choreographer Eun-Me Ahn. Watching clips online, I’m put in mind of other contemporary dance theatre works by the likes of Jérôme Bel (2015’s Gala) and 600 Highwaymen (2013’s The Record) that foreground and celebrate non-professional and mixed-ability performers. “Dancing Grandmothers definitely continues that narrative,” agrees Mitchell. “Eun-Me Ahn asked herself, how do I create an ode to the women who founded Korea? So she jumped in a car with a video camera and drove all around South Korea trying to capture a sense of how South Korean women express themselves through their bodies. She took that footage back to her company of 10 dancers who created a response to it, which forms the first part of the work — a fun, frantic 45-minute sequence on its own. But then you are shown some of the footage Eun-Me Ahn took and you see the grandmothers dancing in their small villages and the like.

“After that, the 10 grandmothers” — Mitchell explains that the group changes every time the show goes on tour — “and the 10 company dancers come out on stage and the 20 of them all dance together, fuelled by disco-inspired Western-Korean pop music. It’s a really quirky series of songs with crazy lights and projections, which reflects Eun-Me Ahn’s personality, but also the vibrancy and energy of these women. Finally, the audience is invited up on stage, and the work becomes a huge disco rave with the grandmothers in the middle of it all. The work is a wonderful celebration of these women, most of whom have never before had the chance to leave Korea and explore the globe.”

Hotel Pro Forma, War Sum Up

In addition to dance, this year’s program also continues Mitchell’s interest in presenting contemporary Asian opera via War Sum Up, a 75-minute electronic opera directed by the renowned Kirsten Dehlholm from Denmark-based company Hotel Pro Forma. Mitchell describes the work as a “powerful, short, sharp, visually striking and musically robust 21st century opera.” He explains, “It forms part of a bigger framework we kick-started last year (with Japanese composer Keiichiro Shibuya’s ‘vocaloid’ opera The End), where we’re thinking about opera not in the context of the traditional Chinese canon but from a global 21st century contemporary perspective. War Sum Up,” Mitchell continues, “is a good example of what I was saying before about moving beyond a geographical definition of Asia and thinking more about what is the influence of Asian contemporary culture globally in the 21st century. With this work, you’ve got a Danish director, a Latvian choir, Japanese Manga for the design, and the libretto, sung in Japanese, is based on traditional Noh texts.

“As a piece of staging,” Mitchell says, “it’s highly visual and the musical range is extremely dynamic. While it’s an opera, there’s no live orchestra, it’s all electronic music, and the actors have microphones, which are used for all kinds of effects and distortion. It’s a work that really pushes against and blurs the boundaries of opera as a form, one that should continue to be rethought and experimented with.”

Promotional image, Secret Love in Peach Blossom Land, Stan Lai and the Performance Workshop, image courtesy OzAsia 2018

Stan Lai, Secret Love in Peach Blossom Land

Relative to War Sum Up, Chinese playwright and director Stan Lai’s Secret Love in Peach Blossom Land looks decidedly traditionalist. 30 years old, the Mandarin-language play is now widely considered a canonical work of contemporary Chinese theatre (though it has not been seen in Australia before). “Stan Lai,” Mitchell tells me, “is a household name in China, much as someone like Baz Luhrmann is here, but for 1.2 billion people. And Secret Love is really the show that broke him and his long career trajectory when it was first staged in 1987.” Not unlike Michael Frayn’s 1982 play Noises Off —Mitchell endorses the comparison — Secret Love is a meta-theatrical comedy about two theatre companies booked by mistake into the same rehearsal space.

“What’s fascinating is that it’s surprisingly fresh and modern,” Mitchell says, “because it’s got a whole meta-theatre narrative running through it, a trend that Lai was way ahead of in my opinion. Part of the reason it looks a little bit traditional,” Mitchell explains, “is because you’re watching two companies stage very traditional shows. You end up watching three plays. One is a kind of memory play where the director is staging something that seems quite biographical around lost love and separation as a result of the Chinese Revolution. On the other hand, there’s a group of young actors, probably not far off graduating from university, who have found an old Chinese text and they’ve decided to reinterpret it as a farce with clowning and sexual innuendo. So, as these troupes try to navigate sharing the rehearsal space, you see their respective plays in the making but also see the backstage circumstances, which include the stage and theatre crews figuring out how to settle their tensions as opening night gets closer and everyone becomes more and more stressed. While it’s farcical, it’s also quite moving and resonant because it touches on themes such as family separation and displacement across borders.”

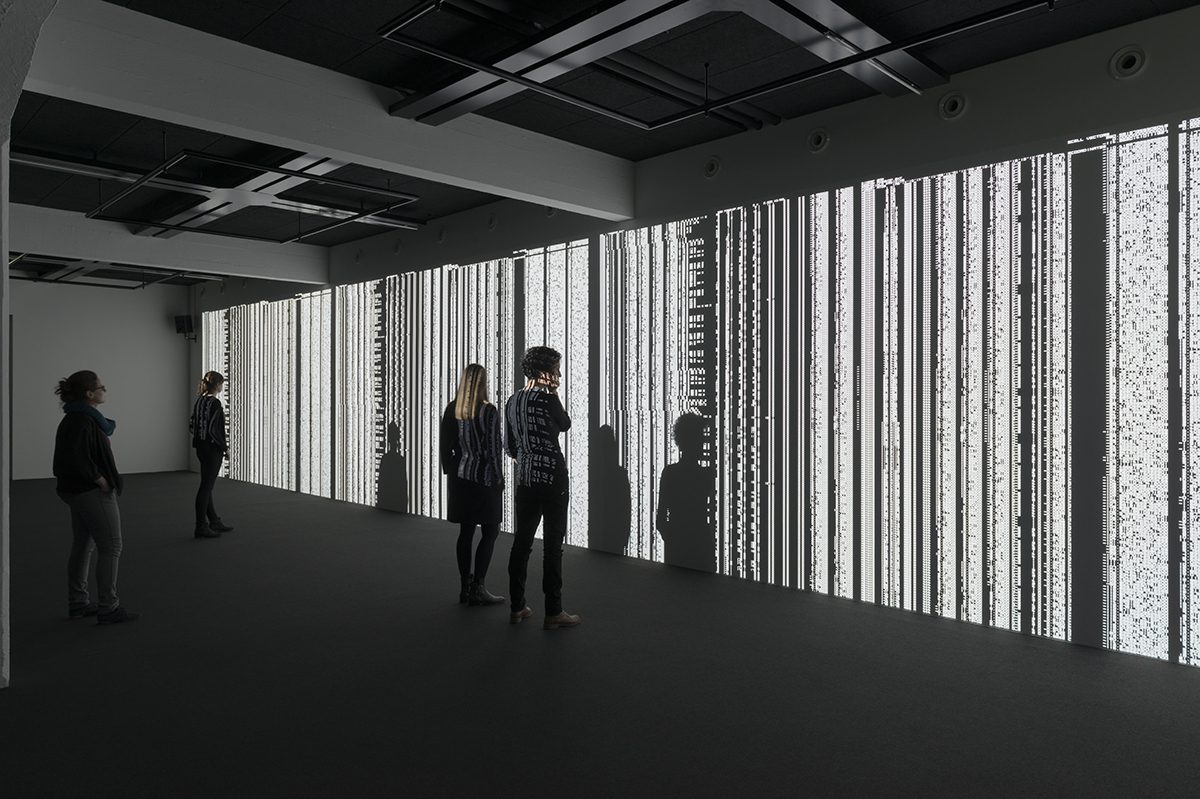

Visual arts: Ryoji Ikeda and Chiharu Shiota

Mitchell is also promising a strong visual arts program this year, tantalisingly hinting at “some very strong links sitting across the various solo exhibitions so that audiences who love the visual arts will be able to look at a bigger emerging thematic picture.” Announced so far are solo exhibitions by two Japanese artists known for their large-scale installations, Ryoji Ikeda — making a welcome return to OzAsia after presenting the intriguing Superposition in 2015 — and Chiharu Shiota, from whom the Art Gallery of South Australia has commissioned a new work, to be exhibited alongside what Mitchell describes as “the first major retrospective of her work.” Ikeda’s data.tron, part of his datamatics series that renders raw data in spectacular 2- and 3D computer-generated patterns, will take up an entire wall of the Adelaide Festival Centre’s Artspace gallery. Shiota’s newly commissioned work, Mitchell explains, will “disrupt one of AGSA’s existing galleries and works by being a significant installation that traverses through the space and around other works in very unexpected ways. It will be very exciting.”

The overall scale of the festival promises to be impressive, reflected in the diversity and richness of work on offer — much of it boundary-pushing or engaged in revitalising conversation with inherited forms. “We’ve got 57 events this year,” Mitchell tells me, “Last year was 50, so it’s our biggest festival yet. 798 artists are coming.” There’s the prospect of another show being “squeezed into the program at the last minute, which I’m quite happy about because it means we’ll end up having over 800 artists. I think we’re in a really good place, particularly with the addition of the Jaipur Literature Festival, which ensures that literature becomes a more significant part of the program.”

While Joseph Mitchell anticipates a more robust conversation about the integration of Asian arts and culture in the Australian mainstream — a grappling with “the multicultural diversity of this country and the place of Australia geographically at the southern tip of Asia” — the OzAsia Festival, under his venturesome direction, continues to point the way forwards.

–

OzAsia Festival 2018, Adelaide Festival Centre, 24 Oct-11 Nov

Top image credit: Eun-Me Ahn’s Dancing Grandmothers, photo Eunji Park