OzAsia: Macau revivified

In our concern with the negative effects of colonialism, we often overlook the enrichment that cross-cultural intercourse can bring. Macau Days offers a glimpse of that enrichment by illuminating the history and mythology of Macau, a 500-year-old European outpost and the first European settlement in Asia. A collaborative work by visual artist John Young, author Brian Castro and composer Luke Harrald, Macau Days includes a book of the same title by Castro (himself of Portuguese, Chinese and English parentage) and Young (Chinese and French-Dutch). All are Australian residents, and both Castro and Young were born in Hong Kong which neighbours Macau. The exhibition demonstrates the human need for travel and migration in personal and spiritual growth.

The beautifully produced and illustrated trilingual book is itself an art object, comprising poems by Castro and Paul Carter inspired by Macau’s colonial history, an introductory essay by Art + Australia editor Ted Colless, and images of Young’s artwork. Castro’s delightful and darkly humorous poems, collectively entitled Macau Days: or Six Poems in Search of a Dish, bring to life six characters he has discovered who exemplify Macau’s history — the Chinese sea goddess Mazu (originating c 960, and whose name may have been the source of the name “Macau”), the Portuguese poet Luis Vaz de Camões (born c 1524), Chinese poet and painter Wu Li (born 1632, an early convert to Christianity following the arrival of the Jesuits), court artist and Jesuit Giuseppe de Castiglione (born 1688), Portuguese writer and Japanophile Wenceslau de Moraes (born 1854) and Portuguese poet Camillo Pessanha (born 1867).

Castro includes recipes that reflect Macau’s multicultural nature and invites readers to prepare their own dishes to recreate the character of Macau on the premise that food is emblematic of culture and identity. He researched his subjects closely and these recipes were evidently the favourites of the six characters — it’s as if we could enter their hearts and minds or become Macanese by eating these tantalising concoctions.

Mazu, Goddess of the Sea, John Young, Macau Days, image courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong

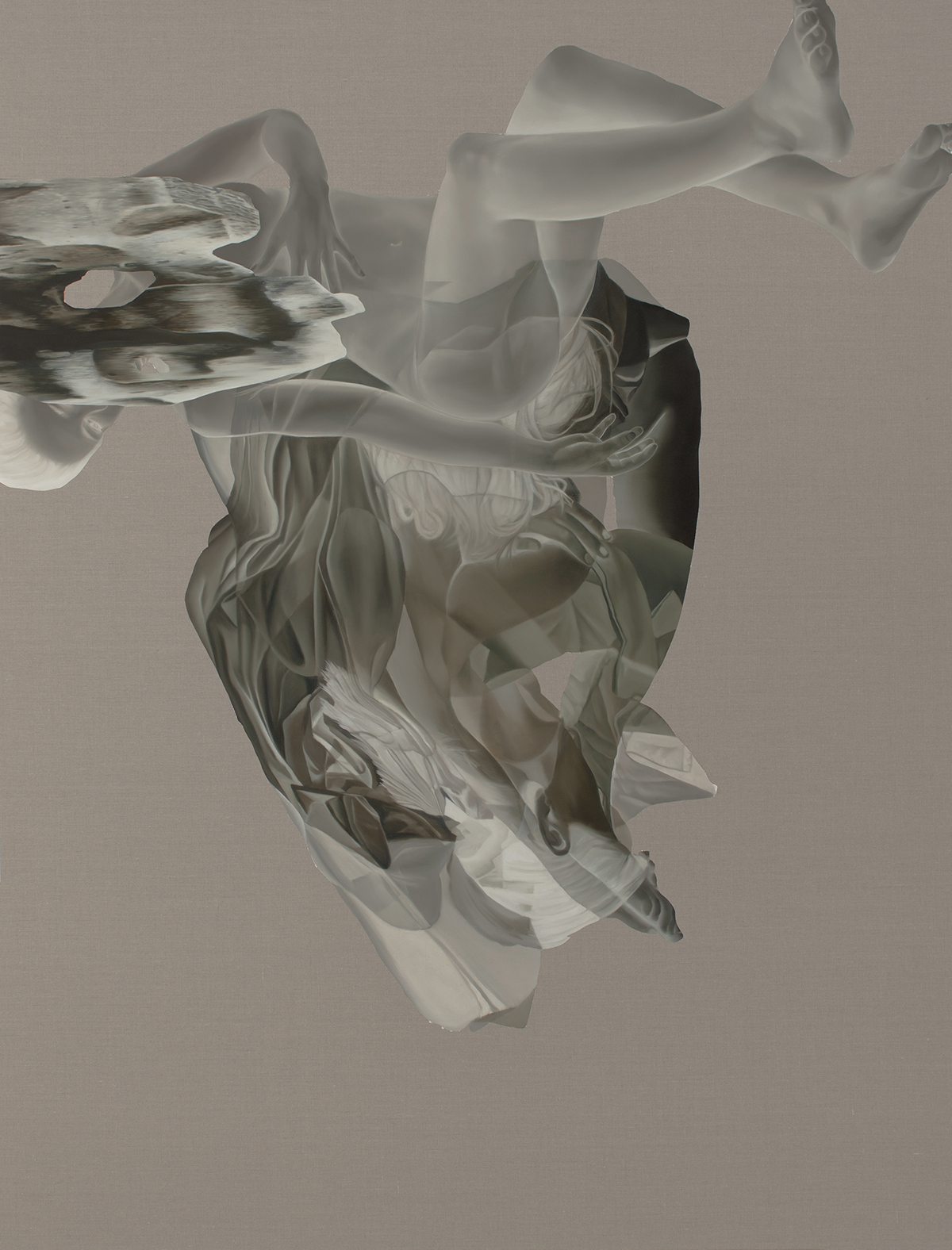

The visual component of the exhibition, John Young’s outstanding Macau Days series (2012), comprises several paintings in which images resembling photographic negatives or digital prints of old photos are overlaid with coloured abstract imagery. The figure of a woman in these paintings evocatively represents the goddess Mazu. A series of digitally reproduced historical photographs evoke the history of Macau with, for example, images of significant buildings such as Jesuit churches and a photo of Wenceslau de Moraes in Japanese garb with a small child. And there are texts chalked on paper painted with blackboard paint, as if lessons were being learnt (perhaps in a Jesuit school). These texts are personal musings, for example “to the ends of the world to find my anima,” “our souls meet here” and “absolutely foreign — see how I became.” Some of these chalk-on-paper works bear erasures and re-inscriptions, as if thoughts have been corrected. Young’s layering, corrections and juxtapositions symbolise the layering and juxtaposition of cultures found not only in Macau but throughout the world.

Luke Harrald’s meditative sound installation is a 21-minute tape loop of voices reading Castro’s poems in Mandarin, Portuguese and English. Depending on where you stand in the gallery, you hear each reader separately and quite distinctly. In the background are field recordings of splashing water, bells, street noises, voices and horses’ hooves evoking old Macau’s aural character. The whole exhibition is an immersive and enchanting experience, part history and part magic realism, and it could only be improved by adding servings from Castro’s menu.

The crucial point of the exhibition is that our subjectivity determines our response to colonisation, migration and cultural hybridisation. Of Young’s artworks, Castro writes: “Having studied Ludwig Wittgenstein/ you know that culture determines/ the way we see; that a person’s name/ is, has to be, the picture of a situation./ Doubled and tripled we crossed borders/ easily; but now the paranoia of ignorance/ has folded up your tapestry/ and it’s a DNA test for ancestry/ which supposedly clarifies how/ humanity runs in generations/ alongside insanity/ depending on the periodic flood/ that brings on the clash of blood.”

The colourful history of Macau shows how travel and migration are long-standing human traditions, precipitating enrichment and development. As Ted Colless puts it in his introductory essay: “In this spectral and sensual liquidity of Macau — a version of the city not so much groundless but ungrounded: a city (as one tourist brochure puts it) with no flora and fauna to speak of — borders become porous or ebb and flow, and the earnest chauvinism of identity politics can be supplanted by mashups and medleys.”

–

OzAsia Festival: Macau Days, artists John Young, Brian Castro, Luke Harrald; Migration Museum, Adelaide, 23 Sept– 8 Oct

Top image credit: Marienbad, John Young, Macau Days, image courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong