performing new form history 1973-86

keith gallasch: mike mullins, the politics of change

Sonya Parton, Keith McDougall, Mike Mullins, Gerard Hindle

photo Richard Bruch

Sonya Parton, Keith McDougall, Mike Mullins, Gerard Hindle

MIKE MULLINS AND I ARE STARING INTO THE PAST, AT OLD PHOTOGRAPHS ON A COMPUTER SCREEN. POINTING KEENLY, MULLINS SAYS, “THAT WAS TAKEN ON MAY DAY WITH GROTOWSKI IN POLAND. MAY 1, 1975. ONE OF THE YOUNG PEOPLE I’VE BEEN WORKING WITH HAS BEEN RESTORING ALL THIS. THERE’S EIGHT HOURS WORK GONE INTO THAT IMAGE. IT WAS SCRATCHED, IT HAD MOULD ON IT THAT HAD GONE HARD.”

I’m appreciative, “It looks so fresh. You could be just down the street.” We’re looking at Mike Mullins’ life in art in the 1970s and 80s: working in the outer limits of theatre, enacting solo performance art, establishing The Performance Space in Sydney and zealously promoting “new form” (which we now know as contemporary or hybrid performance or live art) to the Australia Council.

Mullins will launch this history at Performance Space as a performative lecture on February 16. He takes me through a chapter, a series of images which will be accompanied by recorded voice-overs quoting from letters and articles interpolated with his own live, onstage commentary. “‘Early Experiments’ is about the first original work I did in 1976, in Fitzroy in Melbourne when I came back from Poland. In the lecture I’ll recount how Grotowski referred me to Joseph Conrad’s The Shadow Line and said, ‘That’s you Mike.’ So I took that as a context for the work and developed a piece partly based on Woyzeck but also referencing Conrad’s book, which is about rites of passage. The work was very physically oriented but I started playing with symbols and metaphors. [He points to the image.] This was the performance area—imagine the OH&S on that these days! Here’s the young Margaret Cameron—she must have been 23—and those are slides on two screens.

“I’ll be talking about how the slides gave another dimension to the performance and indeed, one theatre critic wrote quite a good review and Reg Scott in Nation Review actually talks about how this use of photographic images in performance is something unknown at that time. We came to Sydney and performed at The Village Church where the Paddington Markets are now. But then I decided I was doing exactly what Grotowski advised me not to do. The last words he said to me were, ‘Find out what it is that you do. Don’t do Grotowski-style theatre.’ That’s what I was doing. It was a poor theatre, focused on the actor, very physical, quite violent in a way. It made me want to find out what it was that I did. People were doing theatre—with a capital T—based on scripts and there weren’t many of us actually out there exploring new forms of performance.”

out of the box

I ask Mullins what motivated him to write and perform his history. He explains that he recently embarked on a Master of Arts degree and “decided to open about 30 boxes that I’d been carrying around for about 30 years. I’m an obsessive sort of person and an obsessive documenter of my work and of the times. So I’d fill a box, seal it and those boxes weren’t opened until last year. What I discovered when I opened them was that I actually had an historically significant collection of letters, documents, people’s papers, newspaper articles and Australia Council publications, from 1973 to 1986. So I had this little window of time that told the story of the battles that were fought for new form practice. There’s one chapter, ‘The New Form Dialogue’, which is just letters between the Australia Council and me fighting, me accusing them of maintaining a colonial culture, of buying a culture rather than investing in a culture, and attacking the mainstream companies for what I considered to be colonial theatre, carbon-copy theatre. There’s a whole chapter on the production of Nicholas Nickleby as evidence of this with letters between Richard Wherrett and myself and Jim Waites because we’d attacked it for reproducing the achievements of English artists.

“Now, we’ve come a long way—and I’ve been practising this line for some time—when you look at Cate Blanchett sitting passively onstage taking a golden Shakespearean shower, you’d have to say we’ve come a long way since Nicholas Nickleby! And I passionately disagree with [the new artistic director of Opera Australia] Lyndon Teraccini when he says we haven’t come very far since The Summer of the Seventeenth Doll. Well, I’m sorry, but that kind of denies everything that’s ever happened at Performance Space for a start.”

Mullins’ history also includes a chapter on the “ceiling funding strategy” debate of 1985, which he thought extraordinary, not least because it was a serious national debate, but because it lacked the language with which to discuss the issues. The attempt by the Australia Council for the Arts to cap the funding of state theatre companies was met with voluble protest from those organisations as they demanded “certainty”—something the major performing arts organisations have had ever since (if under review next year). Mullins argues that the ‘ceiling funding’ debate really started much earlier, if implcitly, with the collapse of The Old Tote in Sydney and the establishment of the performing arts complexes. “Suddenly the game changed. The state governments created these cultural palaces—Adelaide Festival Centre, 1973, Sydney Opera House, 1973, The Arts Centre in Melbourne, 1984, QPAC, 1985. So not only did a whole lot of arts money go into these complexes but suddenly the budgets of the state companies had to expand. So all this money was being absorbed. And to be fair on the Australia Council and the Theatre Board, the decision they took with the concept of a ceiling funding was the only way they could respond to all the work emerging outside of the mainstream that warranted support. All hell broke loose. I’ve got a wonderful letter from CAPPA [Confederation of Australian Professional Performing Arts] sent to me at The Performance Space saying, ‘Of course we support you but not at the cost of funding to the major companies.’ And my response was, ‘Well what am I supposed to do—wait two decades?’”

thesis as performance

Initially Mullins opened his archive boxes when searching for historical references for the thesis he was writing for a Master of Fine Arts at CoFA. Eventually the research project evolved into a performative lecture, a work of art in itself rather than a conventional thesis or the exhibition that had been considered at one stage. Some of the material had aged badly: “One of my team, Sonya Parton, has just been doing the archive restoration—documents on fading fax paper—and putting it on slides. In one of the boxes I found the fifth carbon copy of the contract between Grotowski and the Arts Council of NSW signed by Grotowski. Gerard Hindle is doing the engineering for the multimedia presentation and the art direction and Keith McDougall is doing the sound design. Plus I’m working with a couple of graduates from the VCA who are doing the voice-overs. So the whole thing is like Media Watch meets Al Gore’s Inconvenient Truth. It’s an investigation, an exposé of a period about fighting for new form, about fighting for the right to pursue new ideas. What really underlies all of this is the question: why is it so fucking hard to pursue new ideas in this country? And it’s not just in the arts. It’s science, industry…What I will show, along with the clinical evidence, is how hard it was for me 1973-86 to pursue new ideas in this country. I ask the question, has much changed?”

Mullins’ archaeological dig into his archive was at moments intensely personal: “There were dead people in those boxes.” But also some revelations. When in 1986 he was asked to do some research for Andrea Hull at the Australia Council about the plight of the individual artist he agreed: “as long as I could in the first instance talk about my own struggles. So I had access to all my files and I discovered that when I was arrested for performing The Lone Anzac on Australia Day 1981, unbeknownst to me all hell broke loose. I found an incredible file of letters from the RSL, from the British-Australia Friendship Society, letters to Malcolm Fraser…It was much bigger than I knew and the Australia Council was under severe attack. It was even raised in the Senate. It was like the Bill Henson case. There’s a wonderful letter from Richard Perram [then a Project Officer at the Australia Council] to Mrs X from Kew in Victoria who thought the whole thing disgusting. He’s writing back to her quoting Gertrude Stein. I ask what’s happened with arts bureaucrats these days? All you get is a pro forma letter.”

For his historical performative lecture, Mullins has drawn on only 20% of the boxed material: “There’s 80% that’s got to be restored. There was a reel of 16mm film that I’d never seen but was shot on the day that The Lone Anzac was arrested. I’ve had that digitised. It was shot on Eastman Colour and colour’s faded, but it’s in there.”

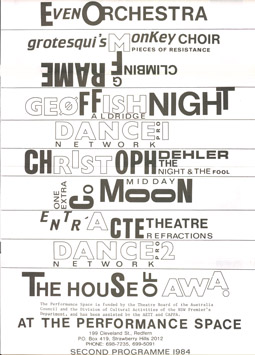

The Performance Space program, 1984

courtesy the Mike Mullins Archive

The Performance Space program, 1984

the performance space years

After establishing The Performance Space in 1980, Mullins says that “the sad story is that my own work largely died because I took on the politics. In 1986 I walked away from the whole thing, exhausted. It took five years of my life and a dole cheque to start up The Performance Space. And many people contributed to that process. I came to an arrangement with the Greek family who owned the building that I’d live there rent free and that I would set it up as a corporate funded body. I have all the letters of rejection from funding bodies. There’s a wonderful one: I have endorsement from one of the seminal figures of 20th-century theatre and I go to the Theatre Board and say I’ve got this introduction from Jerzy Grotowski and I’d like to go to New York and Europe because it will open doors for me. ‘This has no relevance to our agenda,’ says the Australia Council letter.”

I wonder how Mullins kept The Performance Space going until it got funding. “Oh, it was hard. As I explain in the lecture, The Performance Space came about, like most major decisions in your life, from not just one thing. I was working in the Pilgrim Church’s Pilgrim Theatre [over the road from the RealTime office in Pitt Street, Sydney] and because in Shadow Line 2 I had a huge cross that during Act 2 slowly fell, the church kicked me out. Fair enough, I suppose. So I was looking for space but every time you opened a new space it was time and money and energy. Then, after the Luna Park fire in 1979 the Public Halls Act became quite draconian. You couldn’t have a public performance in any church hall anywhere unless it had fire equipment. So the next place had to be the place.

A former trades union hall in Cleveland Street, Redfern, was licenced for public entertainment and “had all the exit signs and fire hoses and all that sort of stuff.” The third reason for establishing a home, Mullins says emphatically, “was that we artists were all working in isolation. I worked out that to do the work, you had to change the thinking of the funding bodies, by having innovative work all happening in one place. But that was the beginning of the end for me as a practitioner because all the energy was going into fighting the battles for change. Hence the title of my presentation, ‘The politics of change.’”

I asked Mullins who were the artists he was supporting and nurturing at The Performance Space. In his boxes he kept all the fliers, listing Dance Exchange, Grotesqui’s Monkey Choir, Even Orchestra, Nanette Hassell’s dance company, Carol Woodward’s Fools Gallery, Entr’Acte, One Extra and many others. “There were the ACT 1 and ACT 2 festivals which is where I did my Agent Orange piece. But The Performance Space also represented a pooling of resources in terms of audiences. It gave them a focus on this work. It gave the funding bodies a focus on this work. My God, it was in a fucking building. They could understand it now! An address. Oh, so that’s new form? 199 Cleveland Street, Redfern. Right! Got it! [LAUGHS].”

Mullins created a range of performances from 1980 to 1986: “Nuke Love (1980); Long Long Time Ago (1983); The Invasion of No-one (Orange Festival, 1985); Illusion (1986); and The Human Exhibit (1984), when I spent three weeks in a cage at Taronga Park Zoo.” His last performance work was Illusion, created with Peter Carey and others (with songs by Carey and Martin Arminger) at the 1986 Adelaide Festival, “for which,” he says, “I got a flogging. That’s a whole other story but an important part of the history. The concept for Illusion was conceived at the Pilgrim Theatre. It was the third part of a trilogy of works I wanted to do: the first two were Shadow Line 2, which was realised, and New Blood which unofficially opened The Performance Space in 1980 when I moved in there. The next work was going to be Illusion but it took me six years to get adequate funding to do it. It was a compromised work in many ways by the end. However, the ABC filmed it and I’m not ashamed of it. I’ve included a section from it in my presentation. It was about Australians pretending to be Americans and getting burned in the process. That’s not a bad statement and how relevant was that during the Howard era?”

investment & a national cultural policy

Reflecting on the rationale for arts funding, Mullins believes a long-term notion of investment in the arts is a good one, “because there’s no quick return. We’re a very young country, a post-colonial settlement, still forming who we are. So investment is very important. I’m a great believer in having a cultural policy because of that. I think we’re very vulnerable to outside influences and we need to protect our identity. That’s got to be the basis of why we have a cultural policy. Who are we? We’re actually quite strange: we’re a massive piece of land with relatively few people on it; we’re isolated by great oceans; we’re in the middle of Asia; we have some of the oldest cultures on the planet, and this idea of multiculturalism—what does that all mean?”

Mullins then looks back longingly to a period of substantial investment: “My chapter on 1973 is full of fantastic things. Whitlam doubles the funding for the arts that year; the first Biennale happens; Blue Poles is purchased; Sydney Opera House opens; Patrick White wins the Nobel Prize; a merchant bank is formed in Sydney called Nugan Hand; Rupert Murdoch registers News Limited in America; the Australian Film Television & Radio School (AFTRS) is established and Al Grasby announces ‘a multicultural society for the future.’ You know, in 1973 women were permitted to sit for the Public Service entrance examination in Victoria for the first time. It’s inconceivable isn’t it? Gilbert and George perform at the Art Gallery of NSW for the first time. And what was I doing that year? I was a trainee director at The Old Tote working on the three opening shows at the Sydney Opera House, pretty well learning everything I didn’t want to do in theatre.”

performing with a purpose

What will Mullins do with his performative lecture after its Performance Space launch? “I’d like to tour it around the country this year. I want it to start a dialogue. All this contemporary practice nowadays has a history. Australia is very good at denying its past. Spaces like Performance Space and Arts House in Melbourne didn’t come out of nowhere. My intention was always to promote the need for a cultural policy. We got real close to it with Creative Nation and I know Andrea Hull was looking at it back in the mid-80s at the Australia Council. I talk about 2110 when there’s been a cultural policy in Australia for 100 years and some kid from a rock near Wagga Wagga comes up with this grant application and it’s for a lot of money because he wants to do the work from the outstation on Mars. It’s a work referencing the red soil of Mars with the red soil of Australia. All doors open, he gets the grant.”

But Mullins isn’t only thinking of emerging artists: “I used to jokingly say about The Performance Space, we’re creating a home for the middle-aged avant-garde. And I was quite serious. Experimental or avant-garde theatre was something you did when you were young. It was never conceived to be a life’s work. And of course it is a life’s work. It’s not something you get over when you grow up. And I see great evidence of that in the work of an artist like Margaret Cameron.”

Mullins would love to trigger change, change that builds acceptance of change, of new ideas, into our culture. He’d love it to be a certainty: “My son has recently graduated as a mathematician and we’re trying to work out a formula, a mathematical equation that explains why art is a critical part of culture. We haven’t cracked it yet.”

The Politics of Change, Mike Mullins and collaborators Gerard Hindle, Keith McDougall, Mike Mullins, Sonya Parton, Performance Space, CarriageWorks, Sydney, February 16, 6.30pm

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010 pg. 38-39