PIAF 2017: A very special place

Keith Gallasch: interview, Wendy Martin, Perth International Arts Festival

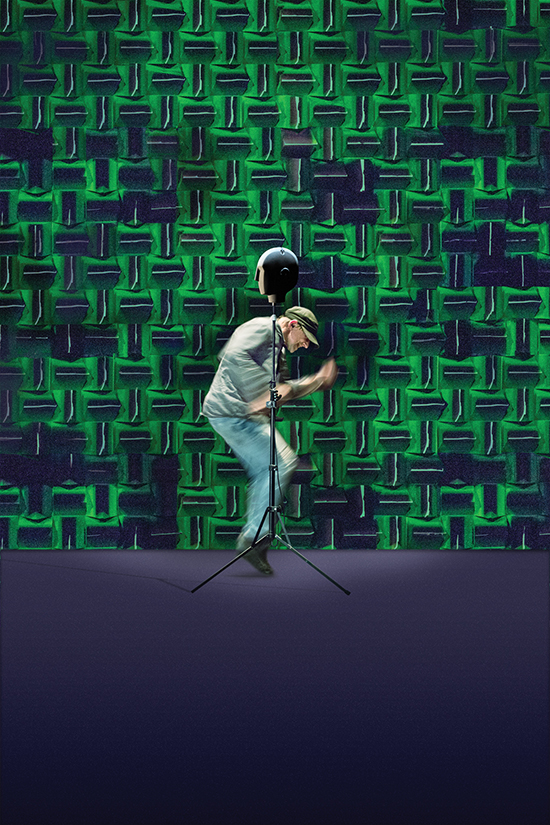

Betroffenheit

photo Michael Slobodian

Betroffenheit

Given the nature of Wendy Martin’s programming of PIAF 2017, it’s tempting to envisage the festival not as a series of events so much as a place to inhabit—an inclusive space, joyfully drawing in all kinds of abilities, communities, ecosystems and sport through the commonality of art.

Like Wesley Enoch, Artistic Director of the Sydney Festival, Wendy Martin has programmed a festival with a passionate sense of social and moral purpose, celebrating the land shared with the Noongar peoples of Western Australia, addressing environmental and asylum concerns and nurturing artists with disability. These are ongoing themes which constellated around empathy in Martin’s 2016 festival. In 2017 place ranks highly: the need to acknowledge and sustain biodiversity, collaboratively with Indigenous communities, and to explore West Australians’ relationship with water in, says Martin emphatically, “the driest state on the driest continent.” Her focus on opening events that celebrate place with local performance, media art and writing—rather than with imported European spectacle—reveals an aesthetic, cultural and ecological commitment to her new home. Here’s a selection of the works Martin and I discussed.

Boorna Waanginy (The Trees Speak)

photo Tori Wilkinson

Boorna Waanginy (The Trees Speak)

PLACE & DISPLACEMENT

Boorna Waanginy (The Trees Speak)

In a large-scale three-night public event, Boorna Waanginy (The Trees Speak) directed by Nigel Jamieson in Perth’s Kings Park, sound, music, light and animated projections will fill trees with the birds and animals of the Western Australian ecosystem. Participating school students are committing to helping preserve particular species.

Museum of Water, Amy Sharrocks

photo Ruth Corney

Museum of Water, Amy Sharrocks

Amy Sharrocks, Museum of Water

UK artist Amy Sharrocks will heighten water awareness—emotionally, intellectually and aesthetically—by collecting citizens’ water stories (and donated water and bottles) at “gathering points” in Perth and Albany.

Martin tells me that Sharrocks has already spoken with farmers, surfers and also a refugee who had been pregnant on a leaking boat when her waters broke prior to rescue. For the 2018 festival, says Martin, Sharrocks will create an Australian version of her award-winning Museum of Water in which visitors meet performers who tell donors’ stories and see related exhibits. When the Rem Koolhaas-Hassell-designed WA Museum is finished in 2020, the Museum of Water will become part of its permanent collection.

A O Lang Pho

photo Nguyen The Duong

A O Lang Pho

Nouveau Cirque du Vietnam, A O Lang Pho

Place plays a key role in works from Vietnam and America, says Martin. In Nouveau Cirque du Vietnam’s A O Lang Pho, 15 performers use large bamboo baskets to conjure a Vietnamese village encroached on by a city, its sounds and music—traditional form giving way to hip hop. You can glimpse the choreographic and unusual design virtuosity here.

The Gabriels

photo courtesy PIAF

The Gabriels

Richard Nelson, The Gabriels

Another village, Rhinebeck, in upstate New York, is the home of leading American playwright Richard Nelson and the setting for The Gabriels, Election Year in the Life of One Family. This eight and a quarter hour trilogy observes a family (including a piano teacher, playwright, costume designer and producer) whose small town is being taken over by wealthy New Yorkers. They prepare actual food and dine, successively, through the confusion of the primaries, mid-campaign and election day. The audience is offered similar food in the intervals. Although in interviews Nelson doesn’t see his plays as political (he thinks Tony Kushner “makes the cut”), they are important barometers of values under pressure in small l liberal America in what he regards as chaotic and confusing times. Martin describes the trilogy as Chekhovian.

The Encounter, Complicite

image Tristram Kenton & Gianmarco Bresadola

The Encounter, Complicite

Complicite, The Encounter

A different sense of place is played out, largely aurally, to a headphoned audience in Complicite’s The Encounter. With an onstage performer-narrator and sound manipulator, the UK company presents an intensely aural experience that recreates a journey up the Amazon via binaural recording (in which the microphones were ear-positioned), acutely reproducing the spatial experience of human hearing. “In 1969, National Geographic photographer Loren McIntyre became lost in a remote part of the Brazilian rainforest while searching for the Mayoruna people. His encounter was to test his perception of the world…” [press release]. The Encounter has been described as sensorily and culturally disorienting. Martin recalls audience members turning, looking for the sources of sound apparently behind them.

Flit, Martin Green

photo Rowland Thomas

Flit, Martin Green

Martin Green, Flit

Flit is a multimedia song cycle on migration created by English experimental accordionist and composer Martin Green, performed with large-scale paper sculptures and whiterobot’s stop animation and played by Green and a formidable trio: Becky Unthank, Mogwai’s Dominic Aitchison and Adam Holmes. Martin tells me that Flit was inspired by both bird migration and the story of Green’s Austrian-Jewish grandmother.

Inua Ellams, poet-performer, artist-in-residence

Martin is excited to have Nigerian performance poet, graphic artist and playwright Inua Ellams as a PIAF artist-in-residence. His Christian father and Muslim mother fled with him to Ireland and then to England. He was 12 when he arrived in London but still does not have a British passport, despite his creative output. Ellams will perform his biographical work An Evening with an Immigrant and Martin has partnered him with Perth’s The Last Great Hunt to conduct audiences on a six-hour journey, The Midnight Run, through “a city you never knew existed.”

Vertigo Sea, John Akomfrah

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea and Auto Da Fé

I saw John Akomfrah’s powerfully immersive, three-screen film installation Vertigo Sea (43 mins) in UNSW Galleries’ Troubled Water exhibition earlier this year. It engenders a kind of contemporary sublime with its visual sweep (from many sources including his own), historical evocation (lone costumed figures on coastal landscapes), dramatic scoring and documentary components, including images of slavery and voiceovers about migration and the flight of refugees. A new work, Auto Da Fé (40 mins), “a fictional narrative that looks at migration over four centuries,” makes its Australian premiere at PIAF.

Jacobus Capone, Forgiving Night for Day

Perth artist Jacobus Capone synthesises place and song in Forgiving Night for Day. On seven locations seen on seven screens, seven Fado singers each greets the dawn in a work that “contemplates the poetic Portuguese word ‘saudade,’ an expression of deep nostalgia and longing for people, places and times irrevocably lost” (program). See images from the work here and hear a little of the beautiful singing here.

PLACE & SPORT

Last year Wendy Martin’s PIAF program featured a British work, No Guts, No Heart, No Glory about empowering young Muslim women through boxing. This year, Martin has two projects. She’s commissioned from Inua Ellams, a basketball addict, a suite of poems about sport and “embedded him in schools that focus on basketball and a youth centre with the highest percentage of Indigenous and African students in Perth.” And she’s programmed a work about women and sport.

Lara Thoms & Snapcat, Before the Siren

In the festival’s visual arts program, curated by Anne Loxley and Felicity Fenner, Melbourne’s Lara Thoms and Perth duo Snapcat are creating a large-scale public artwork about communality achieved by women through sport. It’s timely given the Freo Dockers will be one of the eight teams in the inaugural AFL National Women’s League in 2017. Martin says that the finale will be a party at Fremantle oval, “a cross between halftime entertainment and a political rally.” With works like Before the Siren, Inua Ellams’ poetry and basketball workshops and, in the Sydney Festival, Champions, about women’s soccer (interview) and La Boite’s Prizefighter (review), the relationship between art and sport appears to be flowering (a phenomenon doubtless inspired by Ahilan Ratnamohan’s pioneering football dance).

Opus No. 7, Dmitry Krymov

photo Natalia Cheban

Opus No. 7, Dmitry Krymov

ART & POWER

Dmitry Krymov Laboratory, Opus 7

A highlight of PIAF 2014 was master designer-director Dmitry Krymov’s fabulously playful A Midsummer Night’s Dream (As You Like It) with its giant puppets and players watched by Russia’s new indolent nouveau riche, all fiddling with mobile phones and behaving like aristocrats in the theatre’s box seats. Opus 7 is a more serious work. “A succession of terrible but riveting images,” as one critic put it, the work first evokes the maltreatment by Stalin of Russia’s Jewish population and then, in its second part, portrays the composer Shostakovitch’s oscillation between critique of the state and surrender to its will as his peers were imprisoned or murdered. Recordings of the composer’s propaganda speeches are played but he is realised onstage by an agile actress as a survivor, a Chaplin-esque figure, precisely Krymov’s view of the artist.

The work’s images are persistently surreal—disembodied limbs, a 12-foot Mother Russia (fond but murderous), large photographs of the dead, Jewish figures (like ghosts) painted on a wall by the performers and then cut out, unleashing an enormous storm of torn newsprint; “is this what happens to the truth?” asks Martin. Shostakovitch grapples with three outsize pianos. Such is the challenge to his craft under dictatorship. This is a work I’d travel to Perth to see. You can glimpse some of it in this trailer and, spoiler alert, if you intend seeing Opus 7, avoid longer excerpts from Opus 7 on YouTube.

The work’s title refers to the Scherzo in E flat Major, Opus 7, written by the student composer in 1923-24; it’s already indicative of his characteristic manipulations of mood, playfulness and irony, but just as Stalin was assuming power after Lenin’s death.

Lola Arias, The Year I Was Born

photo David Alarc

Lola Arias, The Year I Was Born

Lola Arias, The Year I was Born

Another work about political oppression is Chilean artist Lola Arias’ The Year I was Born. Martin tells me, “She works in documentary theatre, between fact and fiction. Some years ago in Argentina, where she grew up, she’d created a work with young people whose parents had been murdered by the military government. She was then asked to do the same for young Chileans who appear in the production, their parents victims of the Pinochet regime, and one young man whose uncle was Pinochet’s lawyer.”

DANCE

Crystal Pite & Jonathan Young, Betroffenheit

Leading international choreographer Canadian Crystal Pite has collaborated with actor Jonathan Young to make Betroffenheit, a dance theatre work, says Martin, “about bewilderment in the face of disaster,” in this case the deaths of children. Alex Ferguson, reviewing in Vancouver for RealTime, wrote that, although clearly about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and addiction, “there’s no particular trauma specified but many of us in the audience know that performer Jonathan Young of the Electric Company has sourced his own story… With effort I’m able to pull out of the emotional morass and take Betroffenheit in as a work of art.” It’s a demanding work in which Young speaks the words that run through his mind and a dancer doppelganger gives physical expression to his attempts at survival, climaxing, says Wendy Martin, in one of the most remarkable solos she’s seen.

Anthony Hamilton, Alisdair Macindoe, Meeting

photo Gregory Lorenzutti

Anthony Hamilton, Alisdair Macindoe, Meeting

Antony Hamilton Dance Projects, Meeting

The meeting of the title of Antony Hamilton and Alisdair Macindoe’s dance work is an increasingly complex and fateful one between the dancers and 64 small percussive robots (created by Mcindoe). Jana Perkovic wrote in her review for RealTime, “the movement itself is so precise, irregularly paced and randomly organised, that watching it is never less than mesmerising.” Because Meeting had only been seen in Melbourne in 2015 before garnering overseas acclaim, Martin thought it vital to include it in her program. Hamilton and Macindoe are remarkable dancers, masters of fast intricate articulation and states of temporal suspension.

Meeting Place

With Arts Access Australia, PIAF is hosting a national forum on arts and disability featuring special guest Jenny Sealey, Artistic Director of leading UK disability theatre company Graeae, who co-directed the London 2012 Paralympic Opening Ceremony. Martin says that Sealey’s work ranges across installation, theatre and opera and talks such as “dissecting Sarah Kane’s play Psychosis 4.48 in terms of how access can be made central to artistic decisions.” For PIAF she’ll conduct workshops and deliver talks. For Martin, the forum is part of a four-year commitment, which commenced in 2016 with among other things, revelatory performances by Claire Cunningham.

Wendy Martin’s positioning of Perth and Western Australia as central to her festival, while drawing in international works which connect thematically and excite with new forms, is at once celebratory and exploratory.

Wendy Martin

photo Frances Andrijch

Wendy Martin

PIAF 2017: Perth International Arts Festival

RealTime issue #136 Dec-Jan 2016