Picking at Emma's Nose: Flacco does Freud

Julian Meyrick: Company B, Emma's Nose: A Comedy of Eros

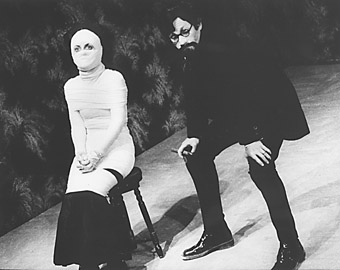

Meaghan Davies, Tyler Coppin, Emma’s Nose

Heidrun Löhr

Meaghan Davies, Tyler Coppin, Emma’s Nose

Freud-bashing has become almost as big an industry as Freud himself. Perhaps that’s inevitable for a man who, like Darwin and Marx, began by shaping our minds and ended by dominating our small talk. His ideas are so much part of the furniture we feel we know all about them without, er, knowing all about them. Or rather we think we know one important thing. In psychoanalysis, Catherine Belsey points out, “everything means something else.” And that something else is, of course, sex. Find yourself fiddling with your pen? Dream about tunnels? Think your partner looks like your Mum? Once these things were coincidences. Next they were insights. Now they are grist for every gag-writer with a line in blue humour who can spell ‘abreaction.’

Emma’s Nose is either a brilliant addition to the anti-Freud industry or a blatant exploitation of it or both. The story doesn’t so much develop as hang like a poisonous vapour over a series of boot-to-crutch skits most of which involve the word ‘penis.’ Emma Eckstein was one of Freud’s patients, a young woman suffering from cramps, hysteria, compulsive masturbation and, according to nose and throat specialist Wilhelm Fliess, ‘nasal reflex neurosis.’ Jacek Koman’s Fliess is a mad-scientist-with-frazzled-hair figure, who’s got a glottal-stop and a theory that abnormal sexual preoccupations (undefined) are linked to noses. He and Freud (Tyler Coppin) shared a belief in the curative powers of cocaine and a 17-year correspondence, most of which involved stroking each other’s egos. In 1895 Freud invited Fliess to operate on Eckstein’s nose. It was his first attempt at major surgery and he left half a metre of gauze in her nasal cavity, to cause in the short-term near-fatal hemorrhage and in the long term, permanent disfigurement. The 2 men parted company but in a gesture bound to impress future researchers, never blamed themselves for Eckstein’s predicament. Amazingly neither did she, going on to become one of Freud’s first disciples and write a book on child rearing.

Paul Livingston (Flacco to you) has mined correspondence between the 2 men to revive a genre harking back to the days of The Legend of King O’Malley: biographical vaudeville. Freud with a German accent and Groucho Marx moustache fingers his cigar and wonders how to greet Fliess. Fliess appears in a puff of smoke, ejected from a side door of Stephen Curtis’ sloping-floor set, waving an antiseptic spray, to harangue spectators with his theories about noses. The humour is relentless, a comedy of bludgeon, the wielding of a single, heavy weapon (the sex reference) over a small area with maximum force: Freud and Fliess sniffing each other’s butts, exploring an olfactory dimension to proboscidal thinking; the doctors two-stepping with canes and top hats; Freud brandishing a talking cigar; and some plain old fashioned clowning (Willy belts Sigmund. “SF: What was that? WF: A Freudian slap!”).

During all this Emma (Meaghan Davies) doesn’t say much because she is swathed in mummy-like bandages. Apart from waddling and waving her arms about all she can do is watch–and bleed. After Fliess operates a considerable amount of the latter goes on. Blood pours, literally, from Emma’s mouth, staining her bandages a deep scarlet and making visible the bottom of her agonised face. She crawls up the sloping floor to escape, but slips on her own fluids and hemorrhages some more. Which rather takes the shine off Fliess’s reputation as a surgeon, although matters calm down after Freud offers him a brandy and the 2 men sniff more cocaine.

I am in some professional awe at the way Company B has managed the risk element of this show. The thin-ness of Livingston’s writing is evident; you can hear the ice cracking behind each line as the actors’ deliver it. Koman and Coppin’s work is a tour de force. If there was any let-up in forward momentum the production would flounder. That it never does is a tribute to the audacity of the whole creative team. To succeed with material like this needs nerve, skill and brains. The best example is the handling of Emma herself. Despite her ‘abject object’ status, she is an electric presence on stage, her eyes registering shades of feeling the slapstick seems to exclude but ends up highlighting. When the blood flows it says more than words ever could about the damage inflicted on an innocent by a couple of obsessed experimenters.

At that point the production goes further than the play. After all, Fliess is the focus of the story, such as it is. Freud gets in only on a guilt-by-association ticket. Knowing a loony isn’t the same as being a loony while the step from a fixation about noses to a theory of sexual drives is a big one, and this play doesn’t take it. Can shows about serious matters succeed if they are just fun? The answer is, of course. It is the worst kind of presumption to criticise a drama for not realising what it never sets out to do. But the production’s stunning handling of Emma’s predicament raises expectations that it might broach the big questions. If it doesn’t, for most spectators that isn’t a problem. The laughs are enough and one can sit back and applaud Company B for pulling it off (in a non-Freudian sense) once again.

Emma’s Nose: A Comedy of Eros, Company B Belvoir, writer Paul Livingstone, director Neil Armfield, performers Tyler Coppin, Meaghan Davies, Jacek Koman, Belvoir St Theatre, Sydney, May 18-June 14

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. web