playing with reality in virtual worlds

christy dena at a monster conference on interactivity

IN A SANDSTONE BUILDING OVERLOOKING A PARK IN FREMANTLE, ATTENDEES TO AN INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE SAT STARING, GIGGLING AND FROWNING AT PROJECTIONS OF VIRTUAL LANDSCAPES, PHOTOS, QUOTES AND STATISTICS. THE EVENT WAS A SPECIAL JOINT CONFERENCE BETWEEN CYBERGAMES: INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE AND EXHIBITION ON GAMES RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT, AND INTERACTIVE ENTERTAINMENT 2006: THE THIRD AUSTRALASIAN CONFERENCE ON INTERACTIVE ENTERTAINMENT.

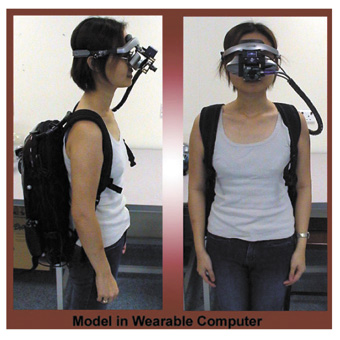

Model in wearable computer, Human Pacman (2005) Mixed Reality Lab, Singapore

Rest assured, participants did go outside and feel the sun on their cheeks, but the chuckling of children playing in the park was no subsitute for the serious study of how people of all ages play in the digital realm. Yusuf Pisan, Technical Chair and Founder of Interactive Entertainment (IE) outlined in the proceedings the motivation behind the conferences:

The interactive entertainment industry continues to grow at a rapid pace worldwide. This expansion needs to be examined not just in dollar amounts they contribute to the economy or the number of people playing computer games, but also in how our everyday interaction is changed and shaped by this new medium. We are defining not just a new field, but a new way of being.

The champions of our evolution are a mix of Australian and international practitioners and researchers from the fields of Artificial Intelligence, Media Studies, Human Computer Interaction, Design, Graphics, Cultural Studies and Psychology. We’ll start with industry. Elina MI Koivisto of Nokia Research gave one of the two keynotes on the “Vision of the Future of Mobile Games.” Nokia is attempting to move mobile gaming beyond the current approach of remediating familiar games like Pacman and Tetris. The company is exploring how the mobile, a device that is always with you and always connected, can facilitate the persistence of game worlds. For instance, they’ve published a cross-platform, massively multiplayer online role-playing game that you can play through your PC and phone: HinterWars: Aterian Invasion (Activate, 2005). Nokia are also looking at the way we interact with these game worlds by exploring applications that allow different input and feedback systems like game pads and motion bands.

Likewise looking at game world persistence and how to produce different ways of interacting is the Mixed Reality Lab in Singapore (www.mixedrealitylab.org). Adrian David Cheok provided lots of photos and descriptions of projects in his talk on “Social and Physical Interactive Paradigms for Mixed Reality Entertainment.” Mixed Reality Lab has created many games that are set in the real world but your actions impact on a virtual world. For example, Human Pacman (2006) involves a person donning a wearable computer and walking down the street. As you walk you devour cookies in the virtual world. Cheok also outlined a few projects that involve playing with your pet. For example, you can play chasey in a virtual world with your real life pet hamster in Metazoa Ludens (2006) or you can pat your hen remotely with Poultry Internet (2004). The lab is also interested in bringing elderly people and children together: Age Invaders (2006) has grandparent and grandchild shooting each other on a dance-floor-like setting with virtual ramifications.

Concerned with how elders (or teachers) can guide young people, Scot Osterweil, Project Manager for MIT’s Education Arcade (www.educationarcade.org), gave a passionate and canny talk on what he terms “learning games.” Games can be used for teaching but many extant ones, he explained, fail because of poor design. Many are created, for instance, with a “content stuffer” approach: they use an existing game platform and inject it with education related content. The result, he jokes, is “Grand Theft Calculus.” Osterweil makes the point that “without playfulness, a game is just going through the motions.’ As a guide, he juxtaposes four freedoms that he believes are the same for play and learning (outside of school): freedom to experiment, freedom to fail, freedom to try on identities and freedom of effort. Arguing that all game play is about learning, Craig A Lindley of Gotland University, Sweden, in “Game Play Schemas: From Player Analysis to Adaptive Game Mechanics”, divides what is learnt into three forms: interaction mechanics (how to interact with the machine), interaction semantics (associative mappings of that interaction) and game play competence (how to progress through the game).

There were five special sessions, the standout of those that I attended was “Experiential Spatiality in Games: Knowing Your Place.” Chaired by Nicola J Bidwell of James Cook University, it included a holistic selection of speakers exploring place, immersion and self. Ulf Wihelmsson of the University of Skövde, Sweden spoke about what he terms the “game ego”: “a bodily based function that enacts a point of being with the game environment through a tactile motor/kinesthetic link.” Wihelmsson argued that the game environment affects a person’s game ego through constraints on what they can do. Andrew Hutchison of Perths’ Curtin University explored how game graphics remove parts of our avatars. He entertained us with examples from games like Half-Life 2 (Valve Software, 2004) where your hand disappears when picking up objects, but is always present when holding weapons; and Doom 3 (id Software, 2004), a game with an extreme graphics engine that performs an array of blood-splatter and shooting effects, but doesn’t give us legs.

Although some games do give us legs, David Browning of James Cook University argued they don’t give us realistic interaction with the terrain. You cannot, for instance, get your feet stuck in mud. Games that are designed for proprioceptivity (using many senses to experience the weather etc) will engage players in the game world more. Georgia Leigh McGregor of the University of New South Wales, focused on the architecture of game worlds comparing World of Warcraft (Blizzard Entertainment, 2004) and Lord of the Rings: Battle for Middle Earth II (Electronic Arts, 2006) and finding that architecture in the former is designed as a spatial experience. The latter, however, treats architecture as an object that cannot be entered and explored. Truna (aka Jane Turner) gave a demonstration of a virtual world that was created to explore archives of the real world. The Australasian CRC for Interaction Design’s Digital Songlines (2005) project (songlines.interactiondesign. com.au) is a virtual landscape of Australia that you can traverse. Your presence in an area triggers local stories, providing a spatial navigation analogous to the manner the stories are recorded traditionally in Indigenous cultures. In her paper, “Digital Songlines Environment”, Truna expands on the culturally-aware design:

The design goal of this project is to reconstruct the Indigenous experience from an Indigenous perspective rather than the usual cultural archiving which tends to prioritise the needs of the database structure and meta-data tags and fields.

Two post-conference workshops, run by Scot Osterweil and myself, provided a more intensive insight into how to design experiences that address audiences rather than system architecture. Overall this first joint conference, chaired by Kevin Wong, Lance Fung and Peter Cole, was a thoroughly enjoyable experience. It was good to have such a cross-fertilisation of topics (only some of them covered here) and to have the chance to debate at length with delegates from around the globe. We didn’t solve what “new being” interactivity is birthing, but had fun in the kindergarten of its evolution.

CyberGames: International Conference and Exhibition on Games Research and Development, and Interactive Entertainment 2006: The Third Australasian Conference on Interactive Entertainment, Fremantle, Dec 4-6, 2006

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 pg. 29