Plotting a cinémathèque

I love films, and I especially love seeing them on a big screen in a dark cinema. I love seeing all sorts of different films: silent films, old films, new films, films from different national cinemas. And while I can find plenty to see, both at the Sydney Film Festival, and the seemingly never-ending stream of national and themed film festivals that crowd the calendar, what I’ve always yearned for is a cinémathèque to provide for Sydney something like the wonderful Melbourne Cinémathèque at ACMI has been doing: a year-round program, a challenging and diverse selection of classic and contemporary films, both retrospectives and thematic series, using archival and new prints sourced from all around the world. I’ve been aware, and jealous of, their program for years; I used to go to Melbourne quite often, and tried to catch a session or two whenever there.

Lost causes

Somehow, however, despite several significant attempts and much talk over the years, Sydney could never achieve anything similar. While it’s often been argued in debates on film culture that not only would audiences profit from such regular screenings of films from other national cinemas, curated seasons of the work of particular directors, screenings of specific genres and of rarely seen gems, but that our own filmmakers and film students could benefit from being exposed to such a rich diversity of filmmaking practice, such ideas have not been enough to make it happen. Suddenly, however, there’s a little ray of hope!

MCA briefly fills gap

Last year I discovered that the Museum of Contemporary Art was having free, curated screenings on Saturday afternoons. I’d already missed some, but I found out in time to see four films by one of my favourite filmmakers, Korean director Hong Sang-Soo, two of which I’d seen but was very happy to see again, and two that I hadn’t—and was delighted with. The next month promised four new Portuguese films curated by film writer and scholar Adrian Martin; the first to screen was Others Will Love the Things I Loved (2014), Manuel Mozos’ loving cinematic essay and tribute to the late João Bénard da Costa, who was apparently a cinephile extraordinaire and one of the most important figures in the history of the Portuguese Cinémathèque (there’s that word again!). I loved this film, even though I knew nothing about either the subject or the filmmaker.

Next in the program were four films by the wonderful Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul. But the MCA did make things difficult—screenings were sometimes changed from the Saturday to the Sunday, or to the next week, sometimes cancelled altogether or perhaps played later (without telling you when). And at the end of the year, they finished; the MCA is now using the screening space for video and electronic artworks, connected to its exhibitions.

A previous try

Ironically, it was the MCA that had spent 10 years from the early 90s trying to achieve a vision of an additional building which would house a cinémathèque, encompassing a national gallery, screening venue and study centre for film, video and computer-based media. But despite many high-powered supporters from the film and performing arts sectora, and many meetings, workshops and architectural competitions, the seemingly interminable negotiations between the many interested parties eventually crashed to a halt. When the additional building finally eventuated, it had only one screening room.

A new approach

I had met James Vaughan, the film enthusiast who had been organising the MCA screenings and who was determined to find an alternate venue and some assistance to continue, and when he asked me to join the Sydney Cinémathèque, the volunteer-run film initiative that has now developed a proposal to put to the Sydney City Council for support, I enthusiastically agreed. James had also been inspired by the Melbourne Cinémathèque. As he says, “I lived in Melbourne from 2012 to 2014 and was a regular [there]. There is no debate regarding Melbourne Cinémathèque’s pre-eminence in Australia for the regular screening of rare, experimental and culturally significant cinema.”

Back in Sydney, talking to film friends and colleagues about the lack of any comparable institution here, Vaughan found many lamenting how long Sydney has been bereft of something comparable, and so, working at the MCA, he worked out a way to utilise its theatre space. That experience has led to the current proposal, a weekly guest-curated contemporary cinema program that would build on the success of the MCA initiative.

As Vaughan explains, the regular screenings would provide the Sydney community with access to rare and culturally significant cinema from around the globe. It would also aim to open a dialogue between acclaimed film practitioners, scholars, curators, and the audience. Guest-curated each month by different Australian and international institutions, filmmakers, critics and festival programmers, it should bring some of the most exciting contemporary cinema from around the world to Sydney audiences.

As Vaughan says, “We see this as a rare opportunity to consolidate and expand on what worked so well at the MCA—the creation of a space for the best curators, critics, theorists and practitioners of cinema to be part of an environment where both complementary and contradicting voices are accommodated to affirm, in all its dynamism, the awesome power of cinematic art. If funded we’ll be seeking curatorial partnerships, and we’re also committed to and passionate about everything which would support the screenings—Q&As, panel discussions and live director Skype-ins. We strongly believe that our proposed program which, at its core, is fascinated by the nebulous zone between conventional narrative cinema and long-form video art, has the potential to revitalise screen culture in Sydney.”

Why a cinémathèque?

The name and the model come from the Cinémathèque Française in Paris, which has had a chequered history since it was founded in 1936 through the passion of the legendary Henri Langlois, who started collecting and preserving films in the 1930s. Dedicated to rediscovering, restoring and conserving all sorts of cinema, to make it available for public screenings, it is the first and most famous institution of its kind and is now a cultural icon in France.

After Sydney became the second international City of Film in 2010, joining UNESCO’s Creative Cities Network, a global network of key cities committed to promoting economic development through their creative industries, filmmaker Gillian Armstrong was quoted in the Sydney Morning Herald as saying that you have to feel slightly embarrassed about the fact that “we’ve been given this incredible honour: City of Film, and we don’t have a cinémathèque, we don’t have a film centre.” Surely it’s time we did.

Our previous coverage of the campaign for a cinémathèque in Sydney appeared in RealTime 96 in which Tina Kaufman traces the history of Australian screen culture and in RealTime RT105 in which she details the campaign in 2011 for a cinémathèque based at the MCA.

–

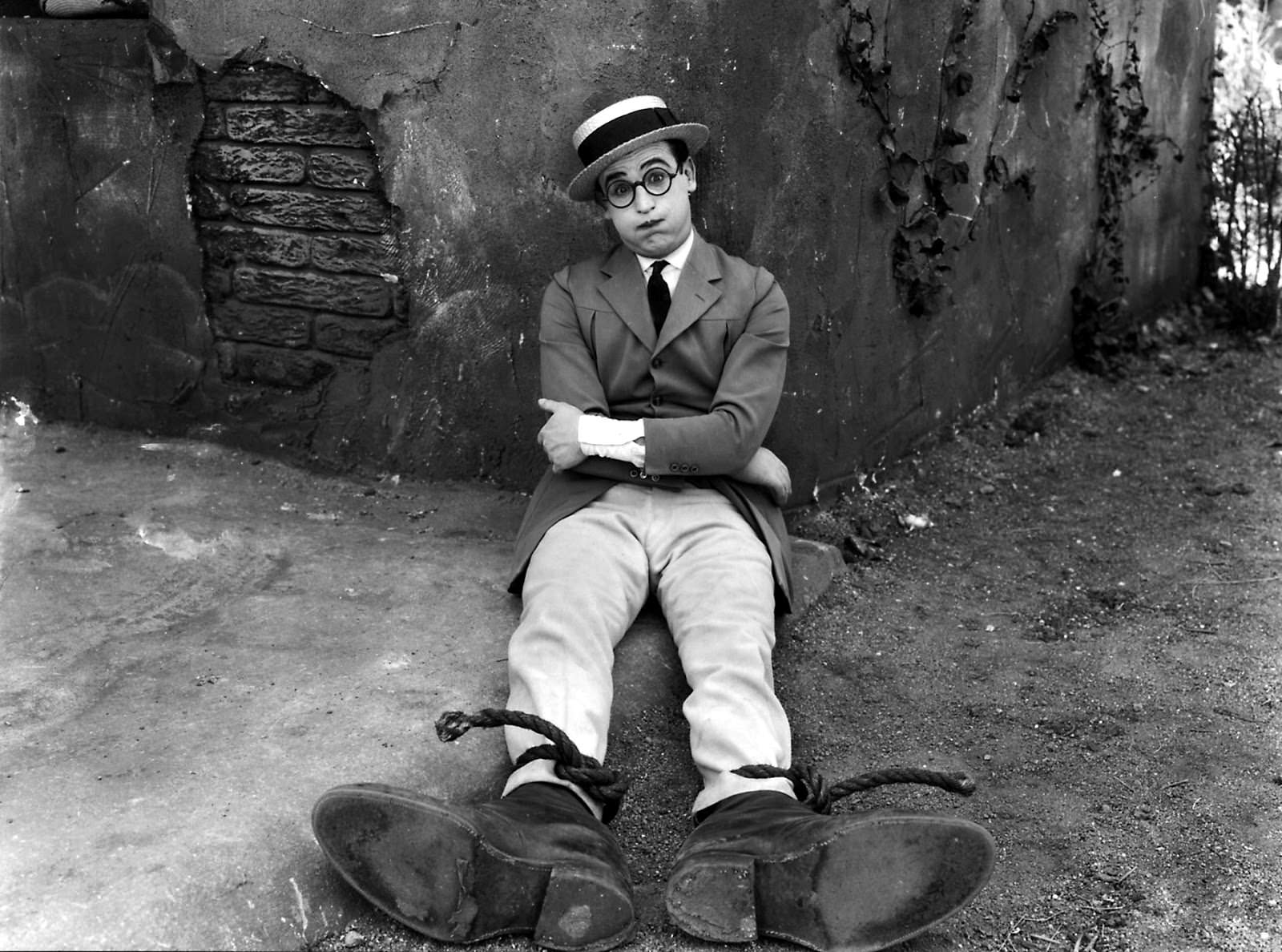

Top image credit: Harold Lloyd, Why Worry? (1923), now screening at ACMI Cinematheque