Poets at risk

Kate Rotherham: Vivienne Walshe, This is where we live

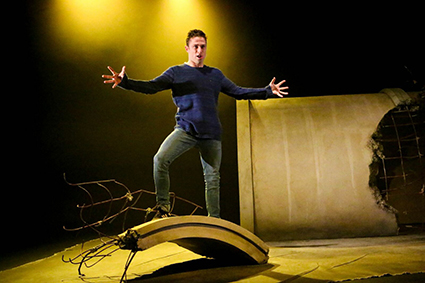

James Smith, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

photo My Wonderland Photography

James Smith, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

A gigantic concrete pipe, reinforcing mesh protruding from its smashed edges and two broken chunks scattered at the forestage, is revealed through a smoky haze. There’s an almost apocalyptic feel as teenage Chloe, in cut off denim shorts over black tights with a checked shirt tied around her waist, saunters onto the stage and hits the audience with a bold torrent of rapid-fire shards from her life. We are instantly pulled into her world and held there in her unflinching gaze.

Chloe (Matilda Bailey) is new to this dead-end town, brought here unwillingly by her emotionally absent mother who has moved in with yet another new boyfriend. Beneath Chloe’s tough exterior lies a complex collision of physical, social and educational disadvantage and a well of unmet needs. Her edgy displacement comes on top of her oceanic grief for her dead father. The ying to her yang is Chris (James Smith), classmate and slightly less-wounded poet. They fall in love against a pervasive backdrop of bullying and hardship and search for a way out.

Playwright Vivienne Walshe has said that she dislikes both the direct nature of language in theatre and the usual delivery of poetry (Time Out, Sydney, 21 May, 2013). Her unique solution is to keep the language fast and tight where the characters reveal themselves to us in gutsy poetic bursts. Chloe’s jagged self-reflections give voice to her bleak inner world. Her dialogue is an energetic mix of flashbacks and present realities with words cleverly substituted for sound effects: “Pad pad, pad to my room.” Chloe shares every thought, mood and movement with us, drawing the audience deeply, and sometimes uncomfortably, into her dark and chaotic life. We watch for signs of hope to sneak in through the cracks as she explores the potential catharsis of Chris’ love.

Walshe offers us kaleidoscopic fragments of language and character to piece together as we can. There is a deep love of language at the heart of this play, challenging us to listen carefully for subtle changes in whichever of the two characters is telling the story. We must stay alert and gather the clues before they scatter and are lost. On top of the internal thoughts and verbal sound effects, the characters question and answer themselves, simultaneously quoting teachers and parents and school bullies. There is a pulse to the language; it is instantly evocative and powerfully rhythmic. After some measured praise from her mean teacher—who’s also Chris’ father—she says, “He’s taking the piss. If he’s taking the piss I will hang myself from his front door. He’s not taking the piss out of me. I stare out the window, watch kids playing handball. I am quietly, quietly, and I hope you’ll keep this one on the down and low. I am quietly bursting with joy.”

Initially Chris and Chloe observe each other, orbiting each other’s worlds while speaking in parallel snippets directly to the audience. As their relationship develops their dialogue also becomes more connected and more directed towards each other. At the high point of their brief union they speak to each other, facing to face as the armour on both sides falls away, before being rebuilt. It’s a cleverly choreographed dance of text, personality and plot as the performers inch closer to themselves and each other.

For all its energy and momentum, the play carries a heavy sense of stasis. Chris and Chloe are locked into this hostile town in the same way their parents are locked into their dysfunctional relationships. Chloe condenses it to its essence when she says, “There’s a place here in the conga line of listless souls with my name on it. Reserved me a seat and everything. Where we live while you hate us.” There is a gnawing sense that nothing can improve here and any possibility for new beginnings will need to be sown elsewhere, far away from here.

We see their decaying family lives up close. Chris’ bullying father and alcoholic mother are a particularly ugly combination of regret and disdain. There’s almost inevitability about the violence between Chloe’s ineffective mother and her new man. Chloe retells it as, “Crash. Oh no! Here we go. Mum spilt the coffee on the lino. Hear them in the kitchen start the funeral march. I’m sorry sorry Brian.”

Playwright Vivienne Walshe has cast her thematic net wide in a layered play about struggle and identity with domestic violence, grief, bullying, emerging sexuality, disability, learning difficulties and disadvantage masterfully woven into the narrative. There is a unique poetic brutality to Chloe, and we glimpse the exposed scaffolding of her vulnerabilities as she shifts away from her default defiance. In one especially powerful scene she is forced to read in front of her class and as she stumbles and falters with her reading we see her bravado fracture. All too aware of her shortcomings she will later ask the well-read Chris, “What’s a poet got that a dyslexic can use?”

Matilda Bailey is superbly sure-footed as Chloe, striding seamlessly along the wide spectrum of internal and external thoughts and moods. We watch her crack open and close over again, as her grief simmers ever closer to her fragile surface. James Smith skilfully takes the character of Chris on a transformative journey from the slumped, painfully shy “Odd-Boy” in his over-sized jumper to an increasingly confident boyfriend who dreams of rescuing “Chloe of the Underworld” from her tormentors and perhaps from herself. The brilliant duo has been expertly directed by Jon Halpin in this complex and densely-packed performance.

Andrew Howard’s musical score of subtle bass booms and intermittent chimes works below the surface, letting the poetic, at times frenzied, text carry the story unimpeded. Scott Howard’s changes of colouring highlight postural shifts, allowing us to zoom in on Chris and Chloe as they circle each other, and any possible future they may have, around the broken pipe.

This Is Where We Live is a beautiful poetry-slam of identity, violence and neglect with a swirling undercurrent exposing the darker truths inherent in staying where you are.

—

This review is one of four from a RealTime intensive, first-stage writing workshop held 1-3 May in Albury-Wodonga in conjunction with Murray Arts and HotHouse Theatre and conducted by RealTime Managing Editors Virginia Baxter and Keith Gallasch. The other writers were Ann-maree Ellis, Sally Denshire and Ruby Rowat whose insightful reviews can be read here.

HotHouse Theatre & State Theatre Company of South Australia, This Is Where We Live, writer Vivienne Walshe, director Jon Halpin, performers Matilda Bailey, James Smith, designer Morag Cook, composer Andrew Howard, lighting Rob Scott; HotHouse Theatre, Albury-Wodonga, 30 April-9 May

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 31