Polarised in Tempe, Arizona

Sophie Hansen on dance and technology at IDAT 99

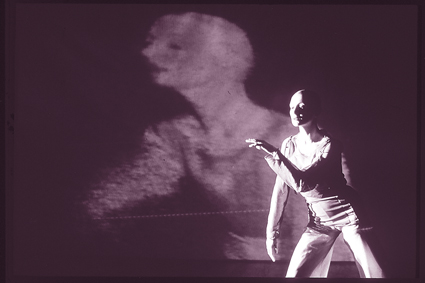

Company in Space, Escape Velociy

photo Jeff Busby

Company in Space, Escape Velociy

Ferocious debate characterised the third international dance and technology conference, IDAT ’99, before it even began. Hosted by Arizona State University in Tempe, this event sought to maintain its status as the foremost international platform for this ever growing field of work—on a tiny budget. So the dance-tech internet mail list blazed for weeks in advance with dramatic vitriol from far-flung artists, angry at the lack of bursaries and fees.

In the event, the international turn-out was impressive, with a strong Australian contingent done proud by Company in Space’s sublime telematic performance in the internet cafe, and the intelligent debate of artists such as Sarah Neville of Heliograph. Whilst there were many Europeans, in particular Brits, who appear to have suddenly woken up to new media in dance, there was naturally a preponderance of Americans and an overdose of academics, so that many of the panels deteriorated into navel gazing. Fortunately the pace of the conference was hot, with 3 events occurring simultaneously at every slot throughout the weekend, so those with an aversion to semiotics were able to busy themselves with workshops and demonstrations.

The potential for creativity offered by pre-existing or artist-invented technologies was clear in the diversity of the performances. The scale of quality was equally well explored. In well-equipped studio and theatre spaces, the presentations ranged from Troika Ranch’s now seminal demonstrations of their patented MidiDancer suit, which alters images and effects in live performance, to the work-in-progress sharings of emerging artists, such as Trajal Harell, dabbling with gadgets in their relation to his mature choreography. There was overwhelming poetry in The Secret Project, a text and movement solo in a Big-Eye environment created by Jools Gilson-Ellis and Richard Povall. The quirky Geishas and Ballerinas of Die Audio Gruppe from Berlin struggled onto a bare stage, to interpret the deafening feedback created by their interaction with Benoit Maubrey’s home-made electro-acoustic suits.

Isabelle Choiniere from Canada offered a terrifying neon-lit Kali figure in her full evening performance, Communion, which scored high for sound and fury but low for the slightest discernable meaning. Local hero, Seth Riskin, took his Star Wars styled sabres to their logical conclusions in Light Dance, an Oskar Schlemmer styled series of tableaux vivants which traced an instructive attention loss curve, where the decline of audience engagement was predicated on the initial impact made by each newly introduced effect. The more we saw, and the more dazzling it at first appeared, the more quickly we grew bored. Jennifer Predock-Linnell had a crack at the good old partnership of dance and film, with strong imagery provided by Rogulja Wolf, and Sean Curran made a small concession to technology by tripping his virtuoso solo in front of some projections. Ellen Bromberg provided the choreography in a collaboration with Douglas Rosenberg and John D Mitchell, and yet her production suffered for its all too well integrated media and fell somehow, slickly slack. Sarah Rubidge and Gretchen Schiller both created touchingly personal environments with responsive performance installation works, and Johannes Birringer and Stephan Silver opened their interactive spaces to marauding dancers in a workshop context.

Many other excellent performances added to the impression of an energetic and abundant art-form, encompassing a dizzying array of practices. There were few shared starting points to be found in any of the events, and this became even more apparent in the debates, which stirred up some exciting disagreements. A panel of artists took on the provocatively titled, “Content and the Seeming Loss of Spirituality in Technologically Mediated Works.” Presentations demonstrated a grounding in the sensual (Thecla Schiphorst’s enquiries into touch and “skin-consciousness” through interactive installations) and the religious (Stelarc’s shamanistic suspensions.) There was talk of the potential for abstraction contained in digitally mediated realms. The informed exchange inspired as many “back-to-basics” anti-technology comments as it did eulogies for hard-wiring and hypertext. Much was made of the fact that new media work in progress is often forced into the guise of finished product, when really it is only the start of a dialogue. The debate polarised; the artist should just dive on in, only this “hands-on” approach will get results; the artist must always approach technology with an idea in mind; technology can only ever facilitate, never create.

At the round table titled “The Theoretical-Critical-Creative Loop”, British artist Sarah Rubidge nailed her struggle to make work and theorise simultaneously by inventing the phrase “work-in-process.” Rubidge is searching for a new way of thinking about the evolving dynamic of productions such as Passing Phases, her installation which offers a route out of authorial control and into the newly imagined realms of genuine audience interactivity. Something innate to the complexity of the technology and its intervention into the experience of the viewer has taken Rubidge’s choreography out of her hands. Still struggling to escape her analytical roots and wary of the ‘inflatory’ language appended to much theorising about this work, Rubidge presented a tentative and thoughtful approach to her parallel roles as artist, academic and writer.

Another British choreographer, Susan Kozel, dissected her approach to the potentially restrictive technology of motion capture. Strapped up with wires, Kozel explores the margins of the technology, testing it to its point of failure. She spoke lucidly about artists working intimately with technology to counteract the idea of depersonalisation. The radical individualism of her appropriation of the motion capture system (to the extent that the bouncing cubes of the animated figure could be “named” according to who was wearing the sensors) was evidence of the vigour of the relationship between the body and technology which she believed to be at the heart of all the work on show in Arizona. There was no shortage of strong opinion at IDAT, and none of it simplistic. Let me leave the last word with a cynical critic from the fiery final panel. Her double-edged sword summarises the conference experience, by provoking exasperation and exhilaration in equal parts, “The more I see of technology, the more I thirst for live performance.”

IDAT 99, International Dance and Technology Conference, Arizona State University, Tempe, Feb 22 – 29

RealTime issue #31 June-July 1999 pg. 35