Positively infectious

Cyber Cultures curator Kathy Cleland talks to Keith Gallasch

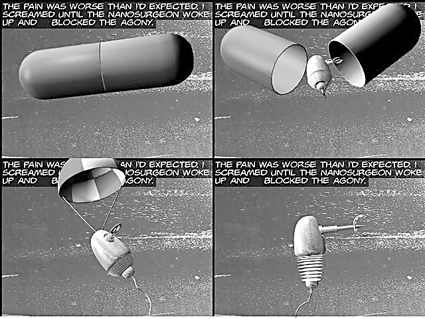

Martine Corompt & Philip Samartzis, Dodg’em 1999

Cyber Cultures has been a huge project, a long evolving thing. Originally it was done through Street Level (the moveable Western Sydney ‘gallery’ Kathy Cleland founded with David Cranswick. eds) and we approached Performance Space and Casula Powerhouse. We were hoping to do a 3-venue thing. As it happened we didn’t get the funding we needed and the whole thing ended up happening at Performance Space in 1996. That show was so popular that we actually managed to get more funding and we did quite a large show at Casula the next year. It really got some new audiences out to the Powerhouse. It was a really big event for the organisation. It required a huge amount of equipment. Nevertheless, out of that grew the idea of doing something more sustained—hence Cyber Cultures: Sustained Release. Instead of having the big bang exhibition where everything happens in a month, we decided to have 4 smaller exhibitions over a longer period which would really help us to build audiences out west. We’re in the middle of developing the touring itinerary at the moment. We’ve had a lot of interest from all over the country.

What seems to happen with new media work is that it’s quite well supported in the more urban centres and the contemporary artspace organisations who’ve got a bit of equipment. But a lot of the regional galleries have very little…so one of the motivations behind the tour this time is to really focus on the regional—particularly regional NSW—and try and tie it in with some training for local staff in how to set up and run and maintain an exhibition like this. Questions I’m asking regional spaces are, do you have a local Apple Centre? Maybe your local council has a data projector? What about the library? So it’s not just going in, doing a show and going out, and there’s nothing left.

What about your choice of works? You have quite a few significant names, award winners, fellowship winners. Is this a kind of ‘best-of’?

I wouldn’t necessarily want to say it’s a ‘best-of.’ It’s a very personal selection. These are people whose work has interested me, some of them for a very long time, some more recently. It’s also seeing what’s out there, what artists seem to be interested in and the directions that the work is going.

In this first stage, called Infectious Agents, there’s obviously some commonality in terms of the idea of infection.

The way the work is being exhibited at Casula it’s all over the building. It’s in these discrete areas that you stumble across. So it’s a bit like the idea of a virus spreading. And I suppose in terms of the tour we’re sending out these little viral pods.

I noted that there are 2 relatively private spaces, one for Melinda Rackham’s Carrier, (see RealTime 37, page 23), the other an adults-only space for Linda Dement’s In My Gash (see Working the Screen page 6) and then a couple are out in the open: the very playful one by Ian Haig called web devolution: a mobile digital evangelist unit (1998) and John Tonkin’s Prototype for a Universal Ideology (2000) and Notes for a Collective Memory (2000) where the user gets into a compositional experience.

It’s been really interesting watching John Tonkin’s works in the gallery. People love them. You can listen to other people’s ideas—either their theory of life or a personal memory which they’ve recorded—and you can cut it up and start mixing and matching it with other things. People sit there for ages. You can see them thinking, no I don’t like that one, I’ll try another one—listening to all these different permutations…

“…forming a gene pool of ideas and memory” says the catalogue. How does Ian Haig’s very playful work fit your theme?

Cyber evangelism. It’s very much like a digital soapbox spewing forth all sorts of crank ideas. That’s how it fits in. The way that the internet and the world wide web have become these huge international fora for mad ideas and the way we’re constantly bombarded from screens.

Other works invite quite a degree of intimacy. Sometimes this can be quite uncomfortable. Navigating Melinda Rackham’s Carrier, you’re implicating yourself in the world of the work.

In the user-notes that accompany that work there are 2 suggested ways of going through it. One is navigating through the linked words at the bottom of the screen but the way you’re describing. which is the best way to do it, is to enter your name and the piece talks to you and asks you questions.

It says, “Hello Keith,” and you have to decide whether to take on the infection and live with the consequences. I was standing there, musing on it and someone standing next to me was saying, oh no you should keep going, move ahead. I said no, no, I’m just absorbing this. Carrier is interesting because it looks like a cross between an informational site with medical data …

… and an incredibly poetic space…

… with 3 dimensional objects rotating in space which appear to be the viral components. Linda Dement’s In My Gash, which has some of the most sophisticated imaging of the 4 works, is full of shocks and surprises, quick-time violence.

I had assumed that Linda would have preferred it to be more of a private piece and that maybe we’d be constructing some kind of housing around a single monitor so it was like a one-person-at-a-time viewing situation. But she’d actually done a few demos more like artists’ talks with the work projected, and she likes the projected quality. So that was her decision. But it is in some ways an uncomfortable piece to watch with other people around.

Next up in the series is Post Human Bodies which we’re launching with a new performance work of Stelarc’s—Movotar. The work’s been in development for a long time. At the moment the pneumatic arm is being constructed in Hamburg. Stelarc’s using an avatar creation, a virtual autonomous body that lives onscreen. That will be projected but the avatar becomes what Stelarc calls a “movotar” in that it can access his fleshbody in the real world. There’s feedback and interaction between Stelarc’s body and the algorithms that are programming the movotar. When they reach threshold states Stelarc’s body will be activated by the movotar driving the pneumatic arm. So it’s kind of a turnaround of the normal avatar where you have a virtual body that represents you in cyberspace. This movotar controls the fleshbody to access the real world. Stelarc’s maintaining control of his legs so he can remain upright.

Jane Prophet, image from The Internal Organs of a Cyborg, 1999

Who’s triggering the action?

The movotar is autonomous. It has its own desires which Stelarc can respond to and override if they are becoming unsustainable.

Also in Post Human Bodies is a new work by Gary Zebington. As well as working with Stelarc, he’s been working on his own CD-ROM, Bodyssey, for a couple of years now. This will be its first public outing. I’m very happy to have the Lump CD-ROM, the project that Patricia Piccinini and Peter Hennessey have been working on for a few years. We exhibited Lump in 1996 Cyber Cultures. So this is the evolved CD-ROM project. Also there’s an international work by Jane Prophet called Internal Organs of a Cyborg which is like a comic book photo story. You know how when advertising agencies need images they go to stock libraries? Well Jane’s been using some of the same images which tend to be of elderly businessmen and beautiful young blondes. She’s created a story involving this woman who’s been a medical test subject for new drugs. There are all these ideas about the medicalised cyborg body. Also this elderly gentleman is about to have heart failure and her heart ends up going to him…The other work in Post Human Bodies is John Tonkin’s Personal Eugenics which has been exhibited in a number of spaces already but I just think it’s a wonderful work and one I really want to get out to the regions.

This is the one where you scan your face…

…and evolve yourself, decide which qualities you like, what you would like to become—more intellectual, more successful. And there’s a Java algorithm you can click on and it morphs your face in different ways. Then you pick the one that looks most like you’d like to be. And you can keep going. You can also play around with other people’s faces—based on what they say they want to be, you can help them evolve to their desired state.

How does Piccinini’s Lump fit in the Post Human Bodies scenario?

This is a completely digital world. The Lumps are digital mutant evolutions which are part human, part something else. When Piccinini was making this earlier on, the babies existed out in the world without a context. Peter Hennessey has created an architecture, like a factory or a museum. It’s like a Lump baby goes home. You go into the incubator and see all the facets of Lump life.

And the third show?

New Life is looking at crossovers between digital and biological life forms and how some of those boundaries are starting to blur. There’s a new work by Jon McCormack called Eden which is, as it suggests, a new world populated by entities that users interact with and help to breed. It’s an online world where you can create a herbivore or carnivore—its head, body and legs can be wheels or little spiky things and then you can track its existence, see how it gets on. I must confess when I tried it all my creatures died very quickly. Other people have had more success.

There are also some younger artists: Kathryn Mew’s Muto which, again, has been around for a little while now but this will be the first time she’s exhibited the work as installation and she’s always wanted to do this. She’s planning to project the work onto a huge weather balloon. Kathryn’s also working with little digital life forms and worlds that have organic as well as digital characteristics.

Anita Kocsis, like Jon and Kathryn, is a Melbourne-based artist. She has a new work called Neonvert which came out of an ANAT residency at Gertrude Street Gallery. It’s like a digital garden which Anita has largely developed on the web. The way she exhibits the work is via video documentation of that event and creating a physical installation around it. There are remnants of real garden and then projected digital gardenscapes. It’s not purely organic. She’s been working with Flash and some of the newer web software to help create it.

What about the final selection?

A fun family one we hope! It’s called Animation Playground and we’re exhibiting Martine Corompt and Philip Samartzis’ Dodg’em which has 2 push pedal cars you can drive round the gallery navigating via a soundscape (see RealTime 33). As you pedal, you trigger different sounds which let you know where various things are. Dogs start barking and you have to go somewhere else. It’s a lot of fun and the soundscape is a huge part of the work. It’s like animation sound meets amusement park. And the other works in that selection are Dream Kitchen, the CD-ROM from Josephine Starrs and Leon Cmielewski which was exhibited at Biomachines at the Adelaide Festival this year and as part of d>art00 during the Sydney Film Festival. What’s interesting about these artists is they’ve done so much work with different types of animation—stop motion, models, all sorts of things. People love it though some are a bit shocked at some of the violence…

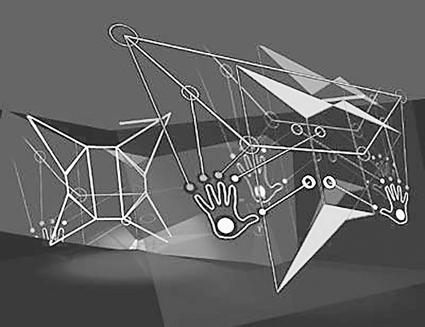

John Fairclough and Maureen Lander, Digital String Games 1998-2000

The pencil-sharpening scene is particularly scary.

…slicing open the rat. There’s a bit of dissection stuff but, you know, eminently enjoyable. There’s also Un-Icon by Mark and John Lycette which is a very simple but very beautiful animation. It takes different screen cursors like the little arrow or the blinking icon and transforms them in amazing animations. They’ll create their own shapes and then whiz off round the screen and then form into another shape altogether—magnifying glasses, arrows. It’s black and white and working very much with computer aesthetics. Very simple but really magical. We also have another work from Martine Corompt, a cute little thing called PetShop which has little animated animals scratching to get out of their TV monitors! And there’s another international collaborative work by Maureen Lander and John Fairclough. Maureen is a Maori artist and this particular piece is called Digital String Games 3. She’s created all these shapes which have cultural resonances for different peoples. They have Maori names but what happens when she leaves out the naming is that people say oh, that means this. It seems everyone has ideas about these shapes. John Fairclough has built an interactive program around it. There are digital handsets so you press buttons or coloured pads and you can create digital strings that link and build shapes as well. There’s an installation with threads that respond to UV light. So it’s a physical installation with a digital overlay. Apparently it’s quite complex and if you’re not successful, things dissolve. So you’re implicated in the cycle of creation and destruction.

As the curator of Cyber Cultures and Chair of dLux media arts, how do you see the health of new media in Australia?

I think organisations like dLux and MAAP in Brisbane and Experimenta in Melbourne are doing amazing things with really very small amounts of money. It’s quite difficult working in this area in NSW because the pools of money are pretty poor. The FTO (NSW Film & Television Office) for example and its staff like Sharon Baker are incredibly supportive but they have such small amounts to give out. It’s hard for us to look at something like Cinemedia in Victoria which has got substantial amounts of money. It’s fantastic what’s happening there and in Queensland as well. I’m a New Zealander and the Labor government there has just committed $86 million to the arts, the arts in general, over 3 years. Organisations like ANAT have been instrumental in supporting so many artists in this area, especially with summer schools and training. That’s been a huge factor for so many of the artists I’ve spoken to in the development of their work. There are some really good things going on in Australia but much more money needs to go into it. And into long-term support for work. It’s like everyone wants something now. And they’re more inclined to give money to a project that’s going to have a quick and very visible result in contrast to something that’s going to develop over a longer time. That’s where the Australia Council New Media Art Fellowships have been good in giving artists that 2 year period for a body of work. And it’s not tied to specific outcomes. Mind you, there usually are outcomes.

Cyber Cultures: sustained release: Infectious Agents, July 7 – August 11; Posthuman Bodies, August 19 – September 24; New Life, September 30 – November 12; Animation Playground, November 18 – December 22; presented by Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre, 1 Casula Road, Casula. Open every day 10am-4pm; www.casulapowerhouse.com/cybercultures [expired]

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 14-