Raghav Handa, Follies of God: A dance for life

“Over-interpretation is just the name we give to the moment when criticism admits — gives a gasp at — the gap between form and content.” TJ Clark, art historian

Raghav Handa’s Follies of God, part of Performance Space’s 2002 Livework’s Festival of Experimental Art, is a physically exacting performance for its maker and viscerally gripping for its audience. It is not dance in any ordinary sense but every movement, even when seemingly involuntary, is crafted from Handa’s Kathak dance heritage and his engagement with contemporary Western dance. It is a work with an agenda, as explained in the artist’s brief program note: a critique of the ill uses to which a sacred text, the Bhagavad Gita, has been put by, among others, Nazis and Hindu nationalists when rationalising the making of “just” war and its framing in terms of “duty.”

For all its physicality and its attested agenda, Follies of God is often mysterious. Symbolic objects and actions compel the viewer to attempt to ascribe meaning as the work unfolds, to make sense of a powerful sensory experience. The alternative is to surrender to the senses, to Susan Sontag’s “erotics of art,” and refuse “the itch to interpret.” That might, inversely, render The Follies of God abstract — as brutally beautiful and compulsively passionate, but without venturing understanding of Handa’s expression of his quarrel with the Bhagavad Gita’s God.

Intuition, gut reaction, deep hearing and the firing of mirror neurons are effectually forms of cognition that can ‘make sense’ of a work, not least when we reflect afterwards what happened to our minds and bodies during the performance — what was felt above what was thought, or transmuting feeling into thought. But Handa’s agenda-driven, imagistic narrative of his successive stages of wrestling with the Bhagavad Gita demand interpretation, to grasp Follies of God’s floating signifiers and to ‘gasp’ at the power of those untethered images.

I embrace the ‘erotics’ of the performance and simultaneously attempt to understand the work, in terms of Handa’s expressed intention, moment by moment. I’m going to over-interpret as I search for meaning. You’ll find me variously guessing and assuming, evident in my ‘maybes’ and ‘it’s as ifs’ and ‘just-don’t knows.’ After writing my response, I had access to a fine video recording of the performance, allowing me to pay closer attention to the work’s sound world and to make some late observations. As well, Raghav Handa kindly answered several questions I posed; his answers, which are illuminating, are found as a postscript to this review.

Prelude

Darkness, a nervy desert wind, mist glimpsed at first light, a strange, thick circular object lying flat to the ground morphing from shadow into a massive, industrial scale, radial rubber tyre, aesthetic, ominous. An ear-bending musical explosion preludes a powerful exhortation from an unseen body: “It happens on the battlefield. The warrior prince and God. Align yourself with me and you won’t incur sin. Red is the extreme and then the blue comes.”

I’m cued, watchful for the red and the blue, for the prince and the god. With Handa’s brief program note and knowing just a little about India’s sacred Hindu text, the Bhagavad Gita, I’m anticipating an evocation of the exchange between Prince Arjuna and his charioteer about the merits of waging a “just” war. The charioteer, I know, reveals himself to be the god Krishna, urging war even if that means the prince will inevitably kill his own relatives.

On the battlefield: First assault

Slowly, secretively, dressed in white, Handa, a soldier on this presumed battlefield, crawls into view, trailing behind him a long, thin, black cable, the rest of it looped necklace like around his upper torso. Cautiously touching the end of the cable to the tyre and yielding sharp aural sparks, Handa curls up defensively against the thunderously explosive, dark chord and its aftermath incantatory chorus of male voices. A tight, white halo forms around the object — holy and obdurately intact; a stand-in, I immediately suspect, for the Bhagavad Gita — it’s sheer size suggestive of the burdensome ethical weight of its argument. And it’s a human construct, just as are the ideological ends to which the text has been put. But detonate it? It’s an aggressive first step.

Investigation

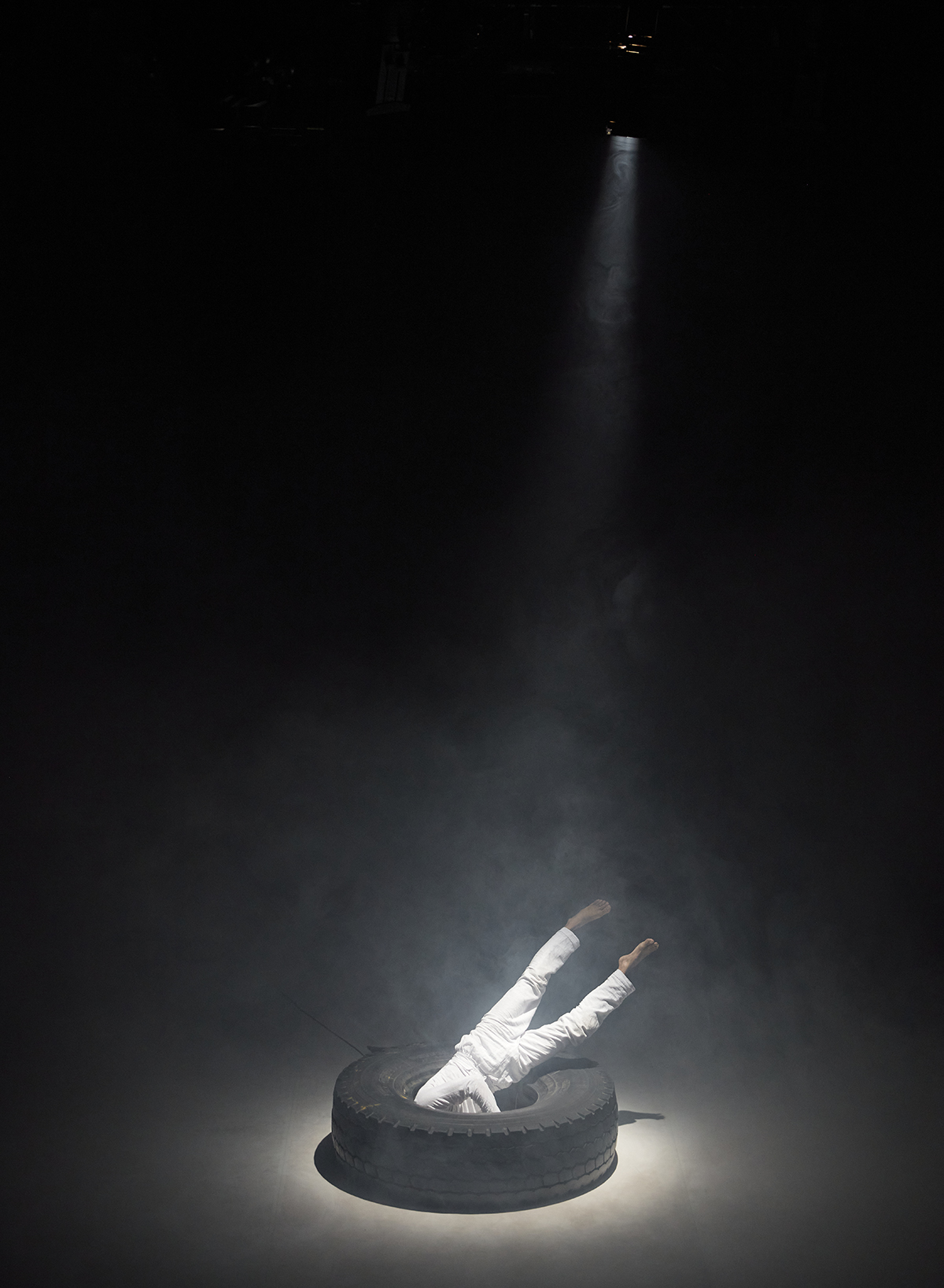

Handa now adopts an exploratory approach, stretching body-length to rest his head gently against the tyre, listening to its unwavering chorusing, now female. But any tentativeness is abandoned when, astonishingly, he dives headfirst into the empty centre of the tyre, his legs outside, locked, pointing up while a voice intones the sacred Sanskrit text. A deep growling suddenly expels Handa from the tyre, leaving him poised over it, panting. A rash quest to go to “the heart of the matter” appears to have been a failure: he emerges exhausted, shocked, unenlightened, footsteps stuttering; the cosmic choir is now threateningly eerie.

Being god and demagogue

The unnerving wind bristles. With great effort, Handa lifts the 250kg tyre so that it stands upright at almost shoulder height, and held so that it doesn’t roll away. He carefully hoists himself to its top, sits, rocks forward and back gently, and then boldly stands. At one with the object and with Krishna, he delivers us a ferocious tirade, alternating between Sanskrit and English, advising, warning, gesturing grandly and with great vocal power: “Fight for the sake of duty,” “Friendship, blood relationship — don’t get involved” “…I will show you how to survive a hand grenade…You will die for me!”

Balancing slightly off-kilter in his passion, he demands, like a terrorist, “No sparks, no flames … We are covered in explosives.” Red light seeps into the space, saturating it as Handa utters a strange collection of seeming nonsenses and non-sequiturs, including: “Your unmanliness will be banned. Thunder will never be green. All weaklings will eat cake. Rust is no longer credible …” “Yellow will slip and break its leg. Your index finger and your thumb will come together to form a union. Peace is not the answer. Rise! Rise! Rise!” He is possessed, he is Krishna and recognisably a language-perverting demagogue.

Warriors in readiness

The red evaporates. Handa drops to the floor, curiously picks up the cable with his teeth and, dog-like, shakes it, striking it again and again to the floor, before rising up, a proud warrior. Encouraged by the call to action just heard and triggered by a burst of antique orchestral martial music, Handa becomes a marvellously convincing procession of military personae — various soldiers, elegant cavalry horse and rider, and an archer, all parading in wide circles. It’s a magical moment, oscillating between pomp and comedy.

Again, possession ceases abruptly. The world turns blue: the calm after exhortation and rehearsal for slaughter, and a return to Handa’s exploration of the mysterious object. He rolls it upstage, giving it voice with the spooky squeal of rubber on tarkett. He whistles into it. Nothing. Hits it percussively. Its beautiful reverberation says nothing. And then, on another tack, with enormous effort, knees weakening and stuck halfway, breaths sobbing, Handa lowers then drops the tyre to the floor with a massive thud, banishing the blue veil.

Into battle

In the ensuing sequence, exactingly sustained, Handa’s probing of the tyre suddenly gives way to (expertly articulated) involuntarism, tossing him to the floor and then rippling fast through his arms and the length of his body — resonant in the pulsing score, with its darkening underlay and an escalating, long-noted, metallic chiming. This is battle. This is the tyre’s power to overwhelm.

Handa feels pain in his right hand and then his right leg, which he worries at with rubbing. He suddenly recovers, posturing heroically and spins furiously, but his drive soon fades. Blue light, but no respite. On all fours, his entire body vibrates furiously; sitting, he thrusts his hand into his mouth and quakes, the score rattling and grinding in parallel, before he attempts another twirling revival, which falters. No blue. Silence.

Wounded, captured

Dazed and clutching his abdomen, a palpably exhausted Handa picks up a hitherto unnoticed, heavy, small black bag, holds it to his stomach, breathes into it, drapes it over his arm, places the end of the cable in his mouth, and turns the bag into a mock helmet, stands assertively, but then lies down, using it now for a pillow. He enters a stage of protracted rest. The bag is a mystery, seemingly hoped-for sustenance, but ineffectual. I’m unable to guess precisely what it represents.

Handa stands warily, drops the ‘helmet’, hands placed on his head as if in surrender, and collapses before soon writhing across the floor and back into life again, taking control of his body to the pulsing of an urgent heart-like pulse in the score with a drumbeat edge. Recovery is fragile: the sudden barking of a dog, an odd intrusion from the everyday, frightens him.

After the battle: Second assault

Blue light and the music of a brassy big band of the 1930s or 40s — with a fragment of its lyrics, “There’s going to be a celebration day” — fill the space. Handa is taken by the music, dances casually, humorously, lifts the tyre to standing, leans against it intimately as if for a mere second finding a dance partner. He rolls it close to us; the blue fades. Handa stands behind the tyre, looks blankly at us and commences to rub and then push his groin against the tyre with increasing force in a protracted, unsensual ‘fuck you’ moment; an extreme provocation, violence perpetrated against the ideological reduction of the Bhagavad Gita to a tool for waging war. Handa lets the tyre fall with a painful thud, the entire space suddenly flushed angry red, music growling.

Red to blue

Now calm, poised, Handa moves centre-stage, turning slowly as a thick mist gathers below and pushes hissing out from above until he is enveloped in red cloud. Sanskrit text (untranslated, unfortunately) is heard again. Less and less visible Handa swirls breathtakingly with increasing speed and apparent grace as if at one with the extremity of red. However, he stops and as he gestures up with his right hand the world turns emphatically blue, his to control it seems, a pallid pool of red fading around his feet.

Final transformation

Handa steps into the centre of the tyre and as his thumbs push into his temples, fingers flaring back, elbows jutting out, eyes rolled up, torso, gut and legs vibrating furiously, there’s a vast rip in the warping soundscape, suggesting monumental change. It’s an incredibly striking final image, another transformation, this time pulsing with possible meanings. Perhaps Handa’s persona has transcended the power of all that the tyre represents and blue, peace perhaps, has finally displaced the extremity of red. But why this strange, quaking figure? Is it a personal figuration of a perpetual struggle for Handa to balance the tensions inherent to the Bhagavad Gita, even in the apparent calm of peace? Or is it, more particularly, Handa as Arjuna, the warrior prince, forever wracked by fear of killing his family in war.

Arjuna shudders

Handa kindly provided me with a copy of the texts spoken in Follies of God. Tellingly, one of the Sanskrit passages spoken by Arjuna, but unfortunately not heard in English, translates as: “My whole body shudders; my hair is standing on end. My bow is slipping from my hand, and my skin is burning all over. If I act many will die, my kin will perish.” The flared fingers, like swept up hair, and the shuddering body confirm the association with Arjuna, correlating with the earlier shudderings of the soldier Handa.

Handa twice assaults the tyre, is seemingly wounded and captured, there is a battle, but there’s no killing in Follies of God (or if there is it’s not made explicit), which tallies with Handa’s belief that the Bhagavad Gita is “not a dogmatic collection of do’s and do not’s. It is a text concerned with larger, philosophical questions about action and inaction.” (Interview, Performance Review, 1 June.) Handa has given vivid physical life to the scared poem’s philosophising by playing out the consequences of succumbing to the obligations of duty or “right action” in participating in an allegedly “just’ war. The intensity and conviction of Handa’s performance suggests a deeply felt personal concern, engaging with a text which is an ineradicable part of his cultural heritage. The title Follies of God, though, feels contrary to Handa’s belief which appears to be that the folly is not God’s but those who misrepresent the Bhagavad Gita for their own ends.

World-making

Deeply entwined design, lighting and sound generate the haunting space which Handa and his apparent nemesis inhabit. The seemingly passive object, oddly beautiful, quite alien, is central to Justine Shih Pearson’s effectively spare design, a living installation. Composer James Brown works visibly from the side of the stage and shares the curtain call with Handa. His live score feels acutely responsive to the performance and in conveying the pervasive realm of the tyre and everything that constellates around it. Appropriate to dealing with a text which is part of a cosmological epic, but without any obvious referencing of traditional Indian music, Brown’s music conjures vast spaces and the immediate pressures of conflict while adding droll down-to-earth moments with the use of brass band and big band music that while Western draw to mind the colonial musical impositions of the Raj. The primary richness of the red and blue lighting states alongside a subtly ‘neutral’ third (lighting designer Verity Hampson) lucidly frame Handa’s successive states of being which dramaturg Vicki Van Hout doubtless helped Handa shape and embody. Above all the real world palpability of the giant tyre and the wracked durability of Handa’s body inside a fantastical metaphysical world, give Follies of God’s quarrel tremendous substance.

I would like to think that in future seasons Handa could trust his audience with a little of the information that follows about the cable and the black bag and some of the spoken text, either in his program note or embedded in the action. I made what I could of these, but felt they placed me at a distance from the performance from time to time, threatening my immediate investment in Follies of God’s emotional physicality. But Handa won me over with his palpable personal investment in his subject matter and his superb craft, even when I felt mystified and compelled into interpretative overdrive which, intriguingly or perhaps perversely, intensified my appreciation of this remarkable 60-minute dance for life.

Follies of God is an utterly distinctive dance-theatre creation, a significant work rooted in cultural knowledge unfamiliar to many in its audience, but who should welcome it. Our sense of the work’s immediacy is heightened by our alarm and anxiety over an unjust war in Ukraine, US-China tensions in which Australia is enmeshed, the rise in general of militaristic rhetoric and the likelihood that we might in our own lives be compelled by a sense of duty to go to or abet war.

Note: The tyre

Handa and his collaborators’ choice of a type of tyre that implicitly represents globalisation is fascinating. It’s used on gantry cranes to move shipping containers on and off board container ships. Globalisation, now in a problematic state, has its advantages, for example in increasing cross-cultural awareness and migration (now increasingly blocked by sovereign state fundamentalism), but equally has a flattening effect due to wealthy nations’ weighty cultural dominance. Like the Baghavad Gita, it’s a matter of how it’s instrumentalised.

Afterword: The cable

Handa tells me that many Indian soldiers in World Wars I and II laid communication cables: “The wire allows me to connect the voices from the past and bring them to our temporality.” Simultaneously the cable represents “the absolute devotion, the coil of expectation on the warrior’s shoulders to put aside their doubts and go to war.”

Afterword: The black bag

The sandbag, weighing 12kg, represents for Handa, “the psychological weight soldiers carry. The image allows me to feel the weight of the ‘right’ action purely through the sandbag as a helmet. It also acts as a device to transport me to the frontier into a battlefield where the soldier is looking down the barrel of a shotgun. Where the soldier faces the consequence of the right action!”

How to survive a hand grenade

Handa told me that he and his sister visited their grandparents in the Punjab at a time when terrorists were killing civilians. His grandfather “would get us to do army drills and take us target shooting. He would teach us how to survive a hand grenade,” as we hear in the initial words in The Follies of God alongside utterances from Krishna. “For me, this is where Follies of God originated. The act of duty … the act of survival and what constitutes as the right action. … [My grandfather] wanted us to be able to defend ourselves. That is why I feel Bhagavad Gita is a scripture of psychology and not a religious scripture… Follies is a pursuit of contemporary truth-telling — put simply, is it ever justified to do bad to do good?”

……

The opening quotation from TJ Clark appears in Hal Foster’s “Not window, not wall,” London Review of Books, 1 December, a review of Clark’s If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present, Thames & Hudson, 2022.

A 20-minute version of Follies of God was one of the eight works commissioned for the 2022 Keir Choreographic Award.

From the RealTime Archive

Keith Gallasch, “Excellent everyday Kathak: Raghav Handa’s TWO,” 26 Feb, 2021

Kathryn Kelly, “The challenges of transformation: Raghav Handa, Mens rea: The Shifter’s Intent,” RealTime 133, June-July 2016

Interview: Kathryn Kelly, “A powerful cross-cultural shape-shifter, Raghav Handa: Mens rea: The Shifter’s Intent,” RealTime 133, June-July 2016

Keith Gallasch, “Likeness unlimited, Sue Healey, On View, Live Portraits,” RealTime 129, Oct-Nov 2015

Jodie McNeilly, “An alchemical progression: Raghav Handa, Tukre,” RealTime 127, June-July 2015

Keith Gallasch, “Brilliance, shimmer & shine, Vicki Van Hout, Briwyant,” RealTime 103, June-July 2011

Performance Space, Liveworks Festival of Experimental Art 2022: Follies of God, lead artist, performer Raghav Handa, collaborator, sound designer James Brown, designer Justine Shih Pearson, lighting designer Verity Hampson, dramaturg Vicki Van Hout, Sanskrit expert, cultural consultant Shashi Handa; Carriageworks, Sydney, 20-23 October

Top image: Raghav Handa, Follies of God, photo Zan Wimberley