RealTime Writing Workshop

Vivienne Walshe, This is where we live

These reviews are the result of a RealTime intensive, first-stage writing workshop for four participants held 1-3 May in Albury-Wodonga in conjunction with Murray Arts and HotHouse Theatre and conducted by RealTime Managing Editors Virginia Baxter and Keith Gallasch.

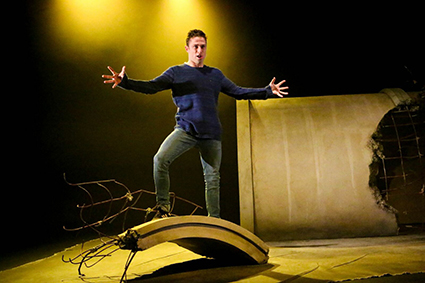

James Smith, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

photo My Wonderland Photography

James Smith, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

Kate Rotherham: Poets In Trouble

A gigantic concrete pipe, reinforcing mesh protruding from its smashed edges and two broken chunks scattered at the forestage, is revealed through a smoky haze. There’s an almost apocalyptic feel as teenage Chloe, in cut off denim shorts over black tights with a checked shirt tied around her waist, saunters onto the stage and hits the audience with a bold torrent of rapid-fire shards from her life. We are instantly pulled into her world and held there in her unflinching gaze.

Chloe (Matilda Bailey) is new to this dead-end town, brought here unwillingly by her emotionally absent mother who has moved in with yet another new boyfriend. Beneath Chloe’s tough exterior lies a complex collision of physical, social and educational disadvantage and a well of unmet needs. Her edgy displacement comes on top of her oceanic grief for her dead father. The ying to her yang is Chris (James Smith), classmate and slightly less-wounded poet. They fall in love against a pervasive backdrop of bullying and hardship and search for a way out.

Playwright Vivienne Walshe has said that she dislikes both the direct nature of language in theatre and the usual delivery of poetry (Time Out, Sydney, 21 May, 2013). Her unique solution is to keep the language fast and tight where the characters reveal themselves to us in gutsy poetic bursts. Chloe’s jagged self-reflections give voice to her bleak inner world. Her dialogue is an energetic mix of flashbacks and present realities with words cleverly substituted for sound effects: “Pad pad, pad to my room.” Chloe shares every thought, mood and movement with us, drawing the audience deeply, and sometimes uncomfortably, into her dark and chaotic life. We watch for signs of hope to sneak in through the cracks as she explores the potential catharsis of Chris’ love.

Walshe offers us kaleidoscopic fragments of language and character to piece together as we can. There is a deep love of language at the heart of this play, challenging us to listen carefully for subtle changes in whichever of the two characters is telling the story. We must stay alert and gather the clues before they scatter and are lost. On top of the internal thoughts and verbal sound effects, the characters question and answer themselves, simultaneously quoting teachers and parents and school bullies. There is a pulse to the language; it is instantly evocative and powerfully rhythmic. After some measured praise from her mean teacher—who’s also Chris’ father—she says, “He’s taking the piss. If he’s taking the piss I will hang myself from his front door. He’s not taking the piss out of me. I stare out the window, watch kids playing handball. I am quietly, quietly, and I hope you’ll keep this one on the down and low. I am quietly bursting with joy.”

Initially Chris and Chloe observe each other, orbiting each other’s worlds while speaking in parallel snippets directly to the audience. As their relationship develops their dialogue also becomes more connected and more directed towards each other. At the high point of their brief union they speak to each other, facing to face as the armour on both sides falls away, before being rebuilt. It’s a cleverly choreographed dance of text, personality and plot as the performers inch closer to themselves and each other.

For all its energy and momentum, the play carries a heavy sense of stasis. Chris and Chloe are locked into this hostile town in the same way their parents are locked into their dysfunctional relationships. Chloe condenses it to its essence when she says, “There’s a place here in the conga line of listless souls with my name on it. Reserved me a seat and everything. Where we live while you hate us.” There is a gnawing sense that nothing can improve here and any possibility for new beginnings will need to be sown elsewhere, far away from here.

We see their decaying family lives up close. Chris’ bullying father and alcoholic mother are a particularly ugly combination of regret and disdain. There’s almost inevitability about the violence between Chloe’s ineffective mother and her new man. Chloe retells it as, “Crash. Oh no! Here we go. Mum spilt the coffee on the lino. Hear them in the kitchen start the funeral march. I’m sorry sorry Brian.”

Playwright Vivienne Walshe has cast her thematic net wide in a layered play about struggle and identity with domestic violence, grief, bullying, emerging sexuality, disability, learning difficulties and disadvantage masterfully woven into the narrative. There is a unique poetic brutality to Chloe, and we glimpse the exposed scaffolding of her vulnerabilities as she shifts away from her default defiance. In one especially powerful scene she is forced to read in front of her class and as she stumbles and falters with her reading we see her bravado fracture. All too aware of her shortcomings she will later ask the well-read Chris, “What’s a poet got that a dyslexic can use?”

Matilda Bailey is superbly sure-footed as Chloe, striding seamlessly along the wide spectrum of internal and external thoughts and moods. We watch her crack open and close over again, as her grief simmers ever closer to her fragile surface. James Smith skilfully takes the character of Chris on a transformative journey from the slumped, painfully shy “Odd-Boy” in his over-sized jumper to an increasingly confident boyfriend who dreams of rescuing “Chloe of the Underworld” from her tormentors and perhaps from herself. The brilliant duo has been expertly directed by Jon Halpin in this complex and densely-packed performance.

Andrew Howard’s musical score of subtle bass booms and intermittent chimes works below the surface, letting the poetic, at times frenzied, text carry the story unimpeded. Scott Howard’s changes of colouring highlight postural shifts, allowing us to zoom in on Chris and Chloe as they circle each other, and any possible future they may have, around the broken pipe.

This Is Where We Live is a beautiful poetry-slam of identity, violence and neglect with a swirling undercurrent exposing the darker truths inherent in staying where you are.

Kate Rotherham is a writer living in north-east Victoria. Her award-winning fiction has been published in magazines, journals and anthologies, including The Best Australian Stories. Her short plays have been performed locally and in Sydney and on the GoldCoast. www.katerotherham.com.au

Matilda Bailey, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

photo My Wonderland Photography

Matilda Bailey, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

Ruby Rowat: Hit me

We’re in the derelict gutter of a desolate underworld. A disused storm-drainage pipe, nearly the size of a caravan, sits burst, grounded on the stage, its jutting steel latticework brutally exposing random jagged ends. A sense of congestion; violently displaced flow. Two hunks of the concrete pipe, steel skeletons awry, have conveniently landed either side of the pipe which is big enough to run through, but, like the harsh, thwarted life of teenager Chloe (Matilda Bailey), there is no flow; no clear route to follow.

We are thrown into Chloe’s reality; it’s her play, the text is her story, miraculously containing all the brittle shards of her life. There is nothing soft or caring in this world. We are put on edge and held there by the masterfully crafted, densely metaphored, race-pace poetry of the script. This barrage of dexterous language demands our attention. There is no rest. No pause. Chloe’s unstable victim mum, sustained constant and irregular humiliations, jabs of physical threats and violent hits. Constantly on the move, new town, new abusive man. Everything seeps into and disrupts everything else, so Chloe’s unsafe home life is right with her in the high school classroom, sabotaging her potential brilliance. There is an adolescent strength and defiance in her character: she is at once a verbosely articulate, self-aware all-seeing know-it-all in her personal narrative, but shattered when she’s put on the spot in class and can barely string together syllables.

Chloe’s “I hear them in the kitchen start the funeral march” sets up the inevitable violence about to transpire. When she’s hit by her mum’s boyfriend, her sense of “…I know where I am. …This is intimate,” was initially foreign, even repulsive, until I related it to the excruciating pain of aliveness when a loved one dies. Definitely a disturbing shock for the audience in this pivotal moment.

Chris (James Smith) brings with him a whole other brand of familial dysfunction, along with a degree of respite from frenzy, with the more measured pace of his delivery. Another, if less wounded poet, an “Odd-Boy” awkward introvert, Chris’ romantic imagination posits Chloe as a limping heroine, a Eurydice for him to rescue. Without specifying the cause of her disability, he describes the limping Chloe as “my one-legged bovine” and her schoolmates taunt her with “spina bifida, spi spina bifuda.”

The clever use of third person pronouns as Chloe and Chris speak of each other, even as they relate in real time, sets up a self-reflective distance between them, in contrast to their emotional proximity. Similarly, their physicality is akin to capoeira dance, without the acrobatics; mostly, they don’t make actual contact. The one time they do hug, it’s that much more powerful.

Rural images—”one legged bovine,” “strictly bucolic,” “classmates in the cattle yard,” “out to pasture”—grimly locate the characters in a regional town. But in a beautiful night-sky moment, Chris lounges against the storm-water pipe, as if leaning against a haystack in a field, while Chloe, at a distance, is lit such that her shadow lies next to him. A deftly woven contrast: fantastic tranquility transposed onto the stark reality of the contorted gnarly pipe and the daily havoc of the teenagers’ lives.

We learn that the “river hasn’t flowed here for three years.” Despite the torrential pace of the performers’ delivery, we are struck by an overall sense of stagnation. Hope is won incrementally. I was initially a bit confused at the abrupt ending of the play. However, given a chance to reflect, the last scenes undeniably move toward healthy prospects coming from a final distressed desire for interaction—”Swivel”, Chloe pleads, across the vast psychological distance from one side of the stage to the other where Chris sits, never turning to look—to an easeful reading of a poem that (finally) acknowledges her father’s death. Then she tells us, “Railway sleepers stand where my spine used to be.”, revealing, metaphorically, that it’s as if an operation for her deformity has straightened her out, allowing her to escape, ultimately to flow: “The train arrives, passing thru my body.” She is transformed: “My whole body shakes…And I’m not afraid. Of what’s coming,” releasing us from the play’s anxious stranglehold into an optimistic potential for life.

Matilda Bailey’s mastery of Walshe’s language is matched by her gestural agility. Each lighting cue, every shift in the script, is accompanied by succinct adjustments in body language. James Smith’s expertise is evident in the unfurling of his hunched-over posture during moments of love or when he strides atop one of the shards of concrete, bright light delineating for us an iconic image of a soldier’s heroic stance, his body and arms all action. Andrew Howard’s spare pulsing music sustains intense emotional moments.

I enjoyed Walshe’s graphic imagery in a script that obliges its audience to constantly connect the dots in order to keep up with the action. The theatrical possibilities offered by the huge storm pipe aren’t fully exploited to inscribe clear movement patterns through and around the tunnel, or atop it to evoke the risk frequently indulged in by teenagers. However the set design certainly magnified a sense of major societal failings and the jarring personal violence tackled in This Is Where We Live.

Now based in Albury, trapeze artist Ruby Rowat toured internationally from Montreal for much of her life. She has also coached across Australia, Canada and Brazil. She continues to perform partner acrobatics on the ground and in the air as she begins to broaden her exploration into voice, rhythm and writing.

Matilda Bailey, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

photo My Wonderland Photography

Matilda Bailey, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

Ann-maree Ellis: In the flood of fear and grief

Twisted and rusted exposed steel formwork protrudes from a large, broken concrete storm-water pipe. Haze and downlights thicken the atmosphere, receding to blackness beyond the pipe. This is where we live: the abandoned back blocks of a regional town. Stagnancy and neglect are palpable.

Chloe (Matilda Bailey) bowls in wearing cut off shorts, black stockings and Doc Martens. A torrent of words flood the derelict space, at once aggressive, poetic, relentless. Very quickly she sketches a picture of her dysfunctional working class family and the familiar angst of adapting to another new town, another new school. I take this in, yet at the same time am not entirely sure what is happening. I’m put off kilter by the barrage of words, directed at the audience, that move a little too fast, range too wide, leave too many gaps.

Straight away we’re put on notice to pay attention, keep up. There is no silence, no stillness of mind, when even pauses are verbalised (“pause pause”) and sound effects are spoken (“gravel gravel, crunch crunch, pad pad”) amid a rush of words that simultaneously convey the inner and outer worlds of Chloe and her new ‘odd boy’ friend, Chris (James Smith). In a continuous stream of poetic language, delivered without apparent punctuation, the two vividly create scenes and an invisible cast of characters. We are hit by the density of their heightened awareness, the fullness and intensity of teenage experience as Chloe and Chris verbally unload their universe on us.

A rather bleak and disturbing universe it is too. When Chloe intervenes to prevent violence to her mum and takes a hit from the drunkard boyfriend, she brazenly confides, “This bit’s hard to explain. You’ll find it in the white trash DNA… When his knuckles make contact I just about cum.” Later she observes the inevitability of hopelessness surrounding her: “There’s a place here in the conga line of listless souls with my name on it. Reserved me a seat and everything. Where we live while you hate us. Where we really live.”

Chris, somewhat awkward and introverted, might seem to have greater opportunities: educated parents, art adorning the walls. But his derisive, controlling father, Donald, and his ‘juiced up’ mother reveal only coldness and bitterness at home. Donald is hard on Chris. He also happens to be his and Chloe’s school teacher. Chloe provokes his disdain at the outset, and Chris can’t measure up to his lofty standards. Donald’s power to either facilitate or hinder their self expression, both as budding poets and young adults, is stark when he helps unlock Chloe’s dyslexic block so she can read aloud, while simultaneously slighting her with his choice of a puerile, sexual limerick.

Navigating plot points within Vivienne Walshe’s dense text is a challenge. Chris and Chloe take turns delivering passages in rapid fire. In a collaged and layered way, they play off one another, picking up on the others’ lines with parallel utterances, yet rarely speaking directly to each other. They engage physically, yet the address is mostly direct to the audience. The poetic phrasing and shifting roles mean at times it’s not clear whether something is past, present or future, metaphoric or imaginary, first or third person.

Just as the audience is kept on their toes, Bailey and Smith are put through their paces as they deal with the momentum and multi-directional nature of the language. While not quite as obviously demanding, the direction and the actors’ physical embodiment of the characters underscores the complex weaving of language. Bailey’s twitching and jutting punctuates Chloe’s outpourings, delivered with an entire physical lexicon full of protective, cultivated and unconscious behaviours that encapsulate her sassy attitude.

As with Rob Scott’s lighting, which changes colour and tone in subtle yet decisive shifts, Andrew Howard’s soundscape is a subtly visceral presence that precisely hits the mark. Seeping in and out, it rises and recedes beneath the voices; an atmospheric bass beat, ever so slightly increases in speed and volume with the emotional intensity of the scene. Neither invisible nor dominant, each of these elements is absolutely integral in creating the perfect conduit for Walshe’s flood of words.

This Is Where We Live is taut, beginning to end. I remained on edge all the way through, engaged by masterful performances and drawn in by poetic dialogue, yet pushed back by its sheer density. I’d have liked more space to appreciate the fullness and complexity of the text and absorb the issues raised. It’s a challenging work that expresses difficult themes.

Reprieve did come, albeit not in a way that could be fully comprehended. If the distressed concrete pipe, solidly central to the action on stage, suggested fracture, then the final image of Chloe breaking through her grief and fear gave a sense of her coming to terms with the emotional and psychological obstacles she must face. I, for one, needed this cathartic end. It seemed that something had to snap in Chloe’s psyche if we were to be given any breathing space in a stultifying narrative that was largely hers.

Ann-maree Ellis lives in Albury where she coordinates the annual literary festival, Write Around the Murray. For many years she maintained a performance practice in dance improvisation and was a founding member of the Melbourne-based improvisation collective, The Little Con.

Matilda Bailey and James Smith, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

photo My Wonderland Photography

Matilda Bailey and James Smith, This Is Where We Live, a HotHouse Theatre and State Theatre Company of SA co-production

Sally Denshire: In the gutter looking at the stars

A shattered concrete storm-water pipe big enough to walk through with skeletal rusting wires exposed evokes a sort of underworld. Chunks of pipe litter the forestage. Composer Andrew Howard’s intermittent bass reverberates through the haze and Rob Scott’s restrained lighting underscores the fluctuating moods in this two-hander in which Chloe and Chris psycho-dramatise their roles of others in addition to their own.

Into this alien landscape stalks 17-year old Chloe (Matilda Bailey) in Doc Martens, tights, cut offs and t-shirt, green-tipped hair and a red checked shirt tied round her hips. A young woman who has been scarred by parental abuse Chloe can experience self-hatred. “Hit me,” she says to her mother’s boyfriend interrupting him doing violence to her demoralised mother. The beating generates a perverse intimacy: “When his knuckles make contact I just about come,” she admits. Chloe speculates that this kind of sexual arousal could “do a girl damage.” As she says, “This is bad. This is bad for my health. What happens to girls with this kind of appetite?”

Her “Odd-Boy” boyfriend Chris (James Smith), who initially describes himself as “a flea on the arse of fresh road kill,” sits with his back to the audience in a dark, baggy jumper, jeans and runners. His body seems almost an afterthought, even though Chloe will later admire his “real six-pack.” The anonymous son of Donald, the pairs’ pedantic, caustic schoolteacher, Chris sets out to rescue the limping, proud “Chloe of the Underworld” from her bullying stepfather and this “one highway” town where people eke out an existence.

Chloe and Chris each voice hopes repeatedly dashed by the brutality of their classroom (where the teacher ineffectually tries to erase a cock and balls drawn in permanent marker on the whiteboard) and their respective damaging family lives. After the beating Chloe avoids school because of bruising on her face. When she asks, “Janelle, have you noticed anything different about me?” her mother “looks up from the crossword, squinting. ‘Have you done something with your fringe?’” “I haven’t been to school for a week,” her daughter retorts.

A yawning psychological distance separates Chloe and Chris and, for the most part, each faces the audience in turn, rather than looking at the other. Gradually they become closer, brothers in arms, momentarily bonding.

Rhythmic bursts of language coalesce as a perfectly formed jewel of brilliant poetic utterance in Vivienne Walshe’s This is where we live. When Chloe’s Dad was alive he had said, with a nod to Keats’ notion of negative capability, “be that thing…what you are looking at, or what you can hear, be that thing and you can disappear. You can go anywhere!” In similar vein, the pair of likely symbolist poets watches a crow up in the sky “fly like it means something more.” When Chris announces “my fantasies are strictly bucolic,” he sounds as if is parroting his teacher-father. Gentle laughter ripples through the audience. When the teacher, supposedly being supportive, expounds on the value of “compact little units of verse, is he actually eroding his students’ confidence to write?

Walshe uses the language of disability and physical difference metaphorically rather than as fixed, diagnostic labels. In the playground, healthy ‘skanks’ repeatedly taunt the limping Chloe to the beat of “Spina bifida, spi, spina bifida.” Chris plays with the idea that Chloe moves differently, describing her vulnerability as “polio dancing with a wayward leg” while Chloe ironically predicts she will end up “dancing for the blind.” But, as she walks with Chris with the same stride, “for the first time in my short order teenage wonder life I walk to class with an even gait.” Sound effects are spoken aloud such as her terminally ill Dad’s “cough, cough,” the “pad, pad” of parental feet on carpet and the “gravel, gravel” of moving around outside. Persisting with medical discourse, in a moment of breakthrough coming to terms with her Dad’s death, she chants the syllables of “me-so-the-li-om-a” (the asbestos-related condition that killed him) in a poem she reads aloud to her class.

Chloe’s scream after reciting the poem exorcises her past and heralds psychological individuation as she struggles to break free from paternal violence and maternal neglect. Will she escape this alien ‘back water’ where she lives?

Chloe and Chris are damaged young people “lying in the gutter…looking at the stars” (Oscar Wilde). Vivienne Walsh has crafted a poetic and multi-layered coming-of-age drama that—as well as offering insights about the young for older audiences—should resonate in particular with the disaffected young who love rap or poetry spoken aloud.

Sally Denshire is an Albury-based writer with 20 years experience in academia. Thirty years ago she established the Youth Arts Program at Camperdown Children’s Hospital in Sydney. Most recently she has published (auto)ethnographic tales of youth occupational therapy practice. Sally is an Adjunct Lecturer, Charles Sturt University, and on the organising committee for the Write Around the Murray Festival.

HotHouse Theatre & State Theatre Company of South Australia, This Is Where We Live, writer Vivienne Walshe, director Jon Halpin, performers Matilda Bailey, James Smith, designer Morag Cook, composer Andrew Howard, lighting Rob Scott; HotHouse Theatre, Albury-Wodonga, 30 April-9 May

RealTime issue #126 April-May 2015 pg. online