Reeldance: the dance-cinema hybrid

Karen Pearlman: ReelDance 2004

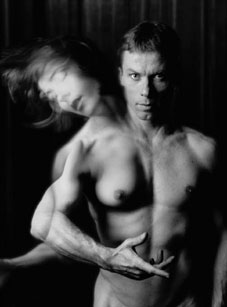

Haunting Douglas

There is a certain confidence in ReelDance’s focus on “everyday movement” in its selections for the Dance on Screen festival this year. The confidence comes out of ReelDance’s own success in the last 4 years, as well as the incredible energy pouring forth nationally and internationally in dance film. The digital video revolution is letting choreographers think into and move onto the screen, creating ideas about the art of moving images that go beyond the limitations of live dance. Dancemakers and ReelDance have left the tired old debate about whether dance film is “really dance” so far behind that they can focus on finding dance in the real.

In fact, at its best moments, the dance on screen in ReelDance was more “real” than live dancing. In Gold (director Rachel Davies, choreographer Hanna Gillgren), a British film in the first program of international shorts, the slam of shots and edits have the kinesthetic impact of what back flips really feel like, not just what they look like on a distant stage. This film uses devices of cinema with breathtaking ease. The brilliant editor and cinematographer formed a partnership with the bodies in motion that made one forget that cinema-dance might be a hybrid. They collaborated with time, finessed the overlapping rhythms of falling and flying, and made space contain stillness and struggle in the one frame.

In the same program, Snow (David Hinton, choreographer Rosemary Lee) also made a dance of moving images, using editing as the basis of its choreographic art. In the first ‘movement’ of this little symphony, tightly edited archival shots of people skating and sliding in a frozen city make lithe, slyly choreographed patterns. In the second half, sleet flings people brutally through storms so extreme that their bodies flail and collide, and the dance is made by the collaboration of the cool handed editor and the whiplash physicality of winter. We feel our own bodies pummelled even in the safety of our warm Southern Hemisphere seats.

In contrast to this choreography by montage, On a Wednesday Night in Tokyo (Jan Verbeek, Germany) made dance with almost no edits. A locked off camera in front of the doors of a commuter train persistently observed the polite, inexpressive faces of people stepping in backwards and shoving hard to make room for themselves. As in the best slapstick comedies, the culture of pressing and positioning while appearing to stay upright and uninvolved is full of both pathos and absurdity.

Sprue (director/choreographer The Five Andrews, UK) achieved comedy through brevity and singularity of focus. Men with red hats imitated time-lapse nature photography by performing a stop-frame animation of flowers blooming. At under one minute it works and is gone. A Function at the Junction (Patrick Newton, choreographer Robert Tannion, UK) spent most of its budget on production design, realising to perfection the faux wood and faux hair of the 1970s. But the low budget faux 70s music was a disappointment, as was the not quite remembered feel of the 70s dancing. In Crazy Beat (John Hardwick, choreographer Carol Brown, UK), 4 tapping teen dominatrixes in blond wigs and knee socks seem to be trying for an ‘Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker meets Quentin Tarantino’ effect. They have the beat but not the bite. Dance Floor (Daniel Mulloy, choreographer Irven Lewis, UK) lovingly integrates life and dance, juxtaposing the complex thoughts and telling images of a female washroom attendant with the complex rhythms of a tap dancer set loose in the adjacent art deco men’s room.

While the opening night program was dominated by Britain and the USA, the following afternoon’s program of international shorts represented the European with productions from the Netherlands, Germany and France. Uzès Quintet (Catherine Maximoff, various choreographers, France) is a montage of 5 works that had been performed separately, and certain aspects of it are thrilling. Each of the choreographers involved represents a different aesthetic strand of French contemporary dance. Playful and passionate dance theatre images are juxtaposed with determinedly formal post-Cunningham dancers, quasi-mystical homoerotic whirling, and a body transformed into a wiry arachnoid. Cutting these dance languages together put them in a conversation about the larger project of contemporary dance. However, the producer’s hand is also visible in this construction: 26 minutes is all the rage in Europe now, being the standard ‘half hour’ for broadcast. But it’s about twice as long as this potential gem needed to be.

Length was an issue in the other 2 ‘shorts’ on this program too. Clara van Gool, whose brilliant productions have featured in both of the previous ReelDance festivals, sets the standard for cinematic dance films that seamlessly mix dance and unspoken drama; real emotion expressed in motion. However, in Lucky (choreographer Jordi Cortès Molina, The Netherlands), the film’s distended setup dissipates the impact of the dizzying kinesthetic and emotional vortexes created by some later sequences.

(Left) Between Us (director Luc Dunberry, various choreographers, Germany) looses cinematic time and energy in sticky sequences that obfuscate some strong images. Luis Buñuel would probably never have thought that he could make a dance without learning technique, just because he had a body. So why would dancers make a “surreal” film about getting stuck in social and communicative conventions without appreciating the work of Buñuel? This is the flip side of the confidence engendered by the DV revolution—the naivety of choreographers who move onto the screen without exposure to cinematic history or ideas.

By the last night of ReelDance, when the finalists for best Australian/New Zealand dance film are screened, it is tempting to look at the dance films on display and start drawing conclusions about national dance film cultures. The British have in common their sometimes cute, sometimes poignant obsession with their lower middle class and its kitsch or inner beauty. The Europeans are preoccupied with mood and saturated images. What of the Australians? In this batch of 10, relationships and loneliness dominated.

Sue Healey’s take on relationships in the prize-winning Fine Line is coolly detached. People caress but not tenderly, they prod but don’t provoke, they dance around each other and the lines that define their dark space. Toy Boy by Fiona Cameron is a stylishly daggy take on relationships: a couch frames the absurd dancing of hungry, feral, and clumsy lust in a singles bar and a blanket in a park makes fairy wings for a fantasy sequence. Cameron’s Sink (co-director Rohan Jones) looks at loneliness or the breakdown of a woman alone, a theme shared by When You’re Alone by Anton and Vacillating by Cameron and Louise Taube. Sink, the third-prize winner, exploits image, colour saturation, framing and editing to create rhythms and ideas. The 3 other works that actively integrated cinematic techniques were Graphic and Rhythmic Study (directors/choreographers Louise Taube and Sue Healey), which is just what it says, but is also pretty wry and stylish; Together (director Madeleine Hetherton, choreographer Rowan Marchingo), which I won’t comment on because my company, Physical TV, co-wrote and executive produced it, and Narelle Benjamin’s second-place winning On a Wing and a Prayer. This succinct and sexy bon bon puts movement inside a simple story structure that allows the performance to mean much more than it seems. On a Wing is sure to do well on the international festival circuit and shows Benjamin’s filmmaking, which could perhaps use a little more focus on space and rhythm, growing in skill and confidence.

I hope ReelDance’s confidence is not diminished by low attendance at its documentary sessions in Sydney. Dance as an art form struggles with a lack of access to its history and cultural context. ReelDance offers a cinematic antidote with dance films that traverse countries and times. It’s a shame for our art form that so few took up the offer.

In Dancing Under the Swastika (director Annette von Wangenheim, Germany) we hear stories that have undoubtedly had an impact on the development of dance in Australia, and experience images of dance escaping tyrannies far more dire than those of distance. The film didn’t just reveal alarming collaborations between the development of our art and the Nazis, but subtextually confronted us with questions about why we dance, and who we dance for.

Even more immediately urgent for the development of dance in our region is the story in Haunting Douglas (director Leanne Pooley, NZ). Douglas Wright returned home to the Antipodes from a substantial international career to find his subsequent work quietly falling off the world map. Sound familiar? Haunting Douglas finds the poetic in this journey and resuscitates the dance before it is lost. Wright’s recalcitrant compliance with the personal interview process is a bittersweet contrast to the emotional daring and physical vividness of his dancing and the graceful generosity of the quotes from his autobiography. He calls his recounting of his personal life, the “pound of flesh” he has to give in order to get his work more widely seen. Together, this ‘blood money’ and his dancing give a rare insight into the harrowing, unsettling, confusing, riveting, searing, satisfying and strange experience of being an artist.

At one point Wright quotes Martha Graham, who said that “a dancer dies twice, once when they stop dancing, and this first death is the more painful.” Wright may have been reluctant to be interviewed, but he did it because he is wise to the gift that dance film, through festivals like ReelDance, gives to dance: life after death.

–

ReelDance international dance on screen festival 2004, Sydney, Canberra, Brisbane, Adelaide, Melbourne, Perth, Newcastle, Auckland; July 30-Oct 9

RealTime issue #63 Oct-Nov 2004 pg. 39