seeing yourself seeing

ella mudie: olafur eliasson, mca; lynette wallworth, carriageworks

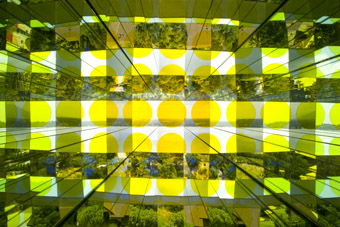

One-way colour tunnel 2007, Olafur Eliasson; Collection of the Art Supporting Foundation to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

photo Ian Reeves Photography

One-way colour tunnel 2007, Olafur Eliasson; Collection of the Art Supporting Foundation to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

WHEN MASSES OF LONDON GALLERY-GOERS BEGAN TO SPONTANEOUSLY SUNBATHE ON THE FLOOR OF THE TATE MODERN UNDER THE HAZY GLOW OF OLAFUR ELIASSON’S ARTIFICIAL SUN FOR THE WEATHER PROJECT IN 2003, THE ARTIST’S INSTALLATION CAPTURED HEADLINES WORLDWIDE. SEVERAL YEARS LATER ELIASSON CONTINUES TO PROVOKE WITH EXPERIMENTS INTO SPACE, LIGHT, NATURAL PHENOMENA AND VISUAL PERCEPTION THAT HAVE ESTABLISHED HIM AT THE VERY FOREFRONT OF CONTEMPORARY ARTMAKING.

This year’s Sydney Festival sees the inclusion of both a large survey of the Danish-born Eliasson’s work, Take Your Time, along with a trilogy of immersive video installations by one of Australia’s most prominent new media artists, Lynette Wallworth, as major components of its visual arts program. Take Your Time, showing at the MCA in Sydney until April 11, first opened at the San Francisco MOMA in 2007 then toured a number of museums in the US where its range of spectacular experiential installations generated a buzz among gallery visitors. Wallworth’s videos carry similarly impressive credentials, exhibited previously to much acclaim both within Australia and at a number of prestigious international festivals, and appearing at the Sydney Festival as a trilogy for the first time.

Sunset kaleidoscope 2005, Olafur Eliasson

photo Fredrik Nilsen

Sunset kaleidoscope 2005, Olafur Eliasson

That two artists so greatly concerned with rewiring the relations between viewer, artwork and the world around us should share top billing is a sign of the times, as a growing number of artists shift their emphasis from the art object to experience and process. Where Eliasson has arguably most effectively differentiated himself is in his refusal to shy away from either visual seduction or spectacle in the exploration of his more abstruse concerns. Whether it’s the creation of shared viewing experiences that overturn the traditional notion of contemplation as inherently solitary, or visual thought experiments that return the viewer to an awareness of his or her own perceptual faculties (“seeing yourself seeing” as the artist puts it), these works reveal beauty and awe as tools to be exploited rather than enemies to be resisted.

360° room for all colours, 2002, Olafur Eliasson

photo courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

360° room for all colours, 2002, Olafur Eliasson

Speaking with Adam Jasper for Sydney Ideas Quarterly in the lead up to the exhibition’s launch, Eliasson pointed out that “art-historically speaking, we stand on the shoulders of generations for whom looking at art was considered such an intimate act that having somebody else in the space would compromise the experience.” In Take Your Time, enclosed spaces refute this tradition by bringing viewers physically closer to one another while, as the mechanics of the works are often made visible, visitors are stimulated to interrogate how the magic is realised. From a fluorescent lit spherical room that places visitors within the colour spectrum (360° room for all colours, 2002) to a darkened, cave-like space in which visitors are drawn toward a mesmerising artificial waterfall (Beauty, 1993), these spaces generate discussion more aligned with the logic of scientific analysis than aesthetic appreciation.

Wandering through this labyrinth of special effects, however, a niggling concern arises that, beyond the initial shift in perception these installations facilitate, there may be limited scope for deeper interpretation. Following this line of thought, suddenly Eliasson’s approach becomes slightly unnerving. Completely a-historical, mainly non-representational, and largely without objects, this is artmaking with all the points on the compass wiped clean. Ultimately, though, this may be an idealistic strategy on Eliasson’s part, one in which art takes place in the present moment liberating the viewer from the encumbering expectations of transcendence, and its accompanying anguishes, handed down from history. And while the artist has insisted “it’s not about utopia or anything final,” it is from this perspective that the works seem most affecting. A quiet plea emerges to use one’s senses, however conditional their production of reality might be, to appreciate nature simply as it is, rather than treating it as a canvas for the projection of our feelings, anxieties and the desire to transform it into something of our own making.

Invisible by Night, 2004, Lynette Wallworth

photo Colin Davison

Invisible by Night, 2004, Lynette Wallworth

Over at CarriageWorks in Redfern, the exhibition of Lynette Wallworth’s trilogy of immersive video installations follows the first major survey of the artist’s work staged at Adelaide’s Samstag Museum in early 2009, which also coincided with the debut of Duality of Light, a groundbreaking moving image artwork commissioned by the Adelaide Film Festival. Like Eliasson’s installations, this trilogy of intimate videos reveal Wallworth’s concern to place the viewer at the centre of the work but, in marked contrast, her approach is very much anchored in the specifics of history, place, identity and personal stories.

In the earliest work presented, Invisible by Night (2004), a life-sized woman appears trapped behind a misty screen and is beckoned to greet the viewer when the video is activated by a touch sensor. This uncanny encounter with a grief-stricken figure represents the artist’s melancholic and empathic response to the site of Melbourne’s first morgue. In a later work, Evolution of Fearlessness (2006), the same touch activation technique is used but here the idea is extended with the portrayal of 11 women, again in life-sized portraits. Some are refugees who have relocated to Australia from various corners of the globe and each has suffered violent persecution. The women’s harrowing true stories of survival are documented in an accompanying text.

In Wallworth’s videos the haptic dimension of the touch screen is not simply about engaging the senses as a challenge to the essentially non-tactile character of the cinematic medium. Rather, it belongs to a larger concern to use gesture, here the simple act of two hands meeting, to engender compassion and expose the viewer to meeting a stranger’s gaze at close proximity—a subversive act in a culture which conditions us to look away. Touch is not harnessed in the final installation, Duality of Light (2009), but again the notion of encounter is significant. In this instance it takes on a more mystical dimension. Immersing the visitor in the sounds of dripping water the installation brings to mind the emotive video works of Bill Viola where water signifies near religious journeys of birth and rebirth. Although here the subterranean sound of water hitting limestone, captured in a cave in Auckland by noted sound artist Chris Watson, leads into deeper recesses of memory becoming, as Wallworth describes it, like “an echo of time.”

Duality of Light, 2009, Lynette Wallworth

photo Grant Hancock

Duality of Light, 2009, Lynette Wallworth

So Wallworth, too, brings the experience back to the viewer with interactive video installations that issue a challenge to feel, to empathise and to relate, that runs counter to an entertainment culture that often demands little more than to sit back and enjoy. Eliasson offers similar challenges in differing ways, yet neither artist denies the audience pleasurable viewing experiences. In fact, the very opposite is true. Heed their advice to look more closely about you and on the faces of fellow visitors at both exhibitions you will find expressions of wonder, surprise and delight.

–

Olafur Eliasson, Take Your Time, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Dec 10 2009-April 11 2010; Lynette Wallworth, Invisible by Night, Evolution of Fearlessness & Duality of Light, Carriageworks Sydney, Jan 7-24 2010

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010