sino-supernova

ella mudie: the big bang, white rabbit gallery, sydney

Wang Zhiyuan

b. 1958, Tianjin

Thrown to the Wind, 2010

steel, plastic

photo courtesy of the artist and White Rabbit Gallery

Wang Zhiyuan

b. 1958, Tianjin

Thrown to the Wind, 2010

steel, plastic

IN LEWIS CARROLL’S TALE IT’S THE WHITE RABBIT WHOSE ENIGMATIC CHARM LURES ALICE DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE INTO WONDERLAND. ART COLLECTOR AND PHILANTHROPIST JUDITH NEILSON RIFFS ON THIS SPRITELY CHARACTER’S ASSOCIATION WITH A SENSE OF SERENDIPITY AND SURPRISE IN THE NAMING OF HER WHITE RABBIT GALLERY, A CONVERTED KNITTING FACTORY IN SYDNEY’S CHIPPENDALE DEDICATED TO SHOWCASING A PERSONAL COLLECTION OF POST- 2000 CHINESE ART. STEPPING THROUGH ITS DOORS HAS THE AIR OF ENTERING ANOTHER REALITY, ALTHOUGH GIVEN THE TITLE OF ITS LATEST AND THIRD EXHIBITION, THE BIG BANG, PERHAPS ‘ANOTHER UNIVERSE’ WOULD BE MORE APPROPRIATE.

Here, The Big Bang refers to “the explosion of creativity that has rocked China since its ‘Opening Up’ to the global economy began in 2000.” This hyperbolic premise had me slightly apprehensive I might encounter an exhibition leveraging some of the now commonly hyped assertions characterising discussions of contemporary Chinese art, and in some respects this is what I found. But when the work is this good, concerns over how a show is marketed are best put to one side in favour of focusing on the art itself. Spread across four gallery floors, this eclectic presentation of works from over 35 artists had me enthralled for hours while also considering a broad array of questions around national versus personal identity, alienation in modern life, cultural amnesia and the role of history in present day China and beyond.

Wang Jiuliang

b.1977, Anqiu City, Shandong

Beijing Besieged by Waste—Guanniufang Village, Xiaotangshan Township, Changping District

40°09’06” N, 116°22’14” E

2009

digital photograph

On the ground floor, two works exploring the flip side of a large population’s increased consumption, its by-product of material waste, stand out for their distinct aesthetic properties. At the rear of the space, Wang Zhiyuan’s spectacular Thrown To The Wind (2010) artfully weaves thousands of discarded plastic bottles around a conical wire frame extending eleven metres to the ceiling, resulting in a whirlwind of waste with a sense of dynamism lent all the greater impact by its overwhelming scale. Nearby, a set of digital prints by Wang Jiuliang, Beijing Besieged By Waste (2009) survey the plethora of garbage dumps that rim the nation’s capital, bringing to mind art writer Carol Diehl’s notion of a “toxic sublime” although the tagging of each photo with GPS co-ordinates emphasises their status as documents. Somewhat at odds with the artist’s environmental campaign is the unwitting beauty in their composition. One image capturing a herd of cows as they scavenge among brightly coloured plastic bags appears almost hyperreal and is eerily tranquil, reminiscent of a traditional pastoral landscape painting albeit with an apocalyptic edge.

Wang Jiuliang’s photojournalism, however, is not characteristic of the majority of The Big Bang artists who prefer to view life through a less literal and more expressionistic lens. Among the most intriguing examples are two mixed media works from multinational Shanghai based art collective, Liu Dao/island6, who work at the interface of art, computers and electronics while seeking to explore “the connections between dreams and waking consciousness.” In Shirt (2009) an LCD screen doubles as a mirror set within a black antique style frame, its surface scratched with finely cross-hatched black lines hinting at an act of vandalism. An infra-red sensor detects the presence of the viewer triggering the projection of an image of a woman onto the mirror/screen where she tries out various poses while dressed in an over-sized men’s business shirt. A witty work, it is also unsettling in its subtle allusion to the voyeuristic impulse that can underscore art viewing and is compelling in its harnessing of technology to delve into the mysterious terrain of desire and the psyche.

The work of Liu Dao/island6 also bears further mention for the way its collective arrangement tests how permeable the boundaries of Chinese art might be. Founded by French artist and curator Thomas Charvériat, now based in Shanghai and drawing artistic collaborators from China, Europe, the US and further afield, this cross-cultural collaboration is certainly a healthy sign of the maturation of the art scene. Yet it also suggests the presentation of contemporary Chinese art may benefit from being geared around more conceptual or thematic lines allowing the work to enter into dialogue with other cultures rather than emphasising its intrinsic “Chinese-ness,” which has become a commodity. This is not to imply The Big Bang is focused on a fixed or historical idea of Chinese art. On the contrary, as its curators point out, much of this work comes from “wired and web-smart products of the one-child policy” who “if their works share a common theme, it is change. And if they have a common perspective, it is ziwo, ‘I myself’.”

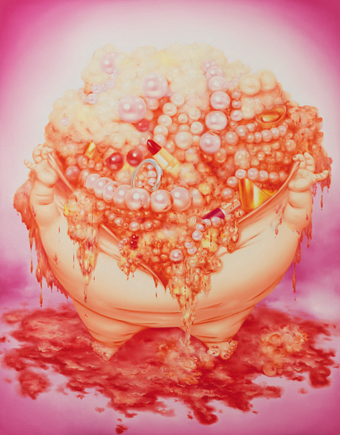

Chen Fei

b.1972, Miaoming, Guangdong

Beyond Satisfaction 2006 No. 2, 2006

oil on canvas

photo courtesy of the artist and White Rabbit Gallery

Chen Fei

b.1972, Miaoming, Guangdong

Beyond Satisfaction 2006 No. 2, 2006

oil on canvas

So then is the individualistic stance of the post-Cultural Revolution generation to be celebrated or deplored? It is a strength of the works on display that a variety of contradictory attitudes emerge. In Chen Fei’s flesh-hued oil painting, Beyond Satisfaction no.2 (2006), the seductive surface belies the grotesque nature of a rotund belly violently split open and spilling forth the shiny goods of feminine desire—pearls, baubles, lipsticks and bands of silver and gold. Clearly here is an artist ill at ease with his society’s relentless desire to consume and accumulate wealth. The attitude of acclaimed photographer and filmmaker Yang Fudong is less easy to pin down. After searching for something sinister in his highly stylised sequence of six black and white film-noir style photographs documenting a well-dressed trio enjoying a night on the town, Ms Huang at M Last Night (2006), it appears the artist is more concerned with challenging viewers to suspend their judgement. As he reflects in his statement “whether you’re filming the life of a rich person or a poor person, there is beauty in both.”

Concluding the exhibition on the gallery’s top floor is a sprawling sculptural installation from Beijing artist Li Hongbo, Paper (2010). Here the artist painstakingly cuts, folds and glues dense layers of brown paper into honeycomb configurations mutating a human figure into a boa constrictor-like form that threatens to engulf the entire space. Dubbed the “slinky man” it is arguably among such supremely confident large-scale sculptural works that The Big Bang really comes into its own. These works might be referred to as “statement pieces” and while some might scoff at the term it is important to remember this is a privately funded collection and as such it reflects an individual’s taste and preferences. Given White Rabbit represents such an extraordinary gesture of philanthropic generosity, this does put up barriers to critique one wouldn’t necessarily encounter in a public museum. Still, where the absence of red tape perhaps weakens the curatorial rigour it also loosens constraints, opening up other opportunities. For viewers, here is a chance to encounter a big, bold and exuberant collection clearly driven by a genuine passion for Chinese art and culture. Certainly the gallery’s label of an “artistic supernova” appears a fitting one.

The Big Bang, White Rabbit Gallery, Sydney, Sept 3 2010–Jan 30 2011; www.whiterabbitcollection.org/

RealTime issue #98 Aug-Sept 2010 pg. web