Slow down, let the cosmos exist: Interview with Michel Chion

You cannot press ‘pause’ on a sound. Well, you can, but once paused, it is no longer the same sound. The duration, and thus the timbre, the tone, the effect of a sound, is altered. Indeed, if paused, a sound simply becomes a void. An image can be frozen in time, lifted out of the many images around it and examined in detail, but a sound cannot; pressing ‘pause’ on a tape player will only create silence, or perhaps the gentle humming of an idle speaker.

Michel Chion often writes about pausing sounds, and the way that sounds transform in different conditions, different scenarios. A French writer, composer, filmmaker, and sound theorist, it is impossible to capture Chion’s body of work in a single essay, impossible to cover everything of interest in a single conversation. He refuses to call himself an authority, but his output would suggest otherwise, as his books, and their translations, are widely read and taught at universities across the globe. In Sound: An Acoulogical Treatise, recently published in an English translation by James A Steintrager, Chion writes that “observing sounds is like observing clouds rapidly streaming.” This nod to the ephemerality of nature evokes a world across its spectrum, from tranquility to wild havoc. Sound is always coming and going around us, constantly shifting and forming new shapes and reverberations. It is respiration, it is the ebb and flow of the sea, an introduction and a disappearance, a negotiation of harmonic spectra. It is both natural and artificial, a product of deliberate design and construction.

Sound exists in time, and so always exists. Chion’s expression “frozen sounds,” he tells me, “considers that it’s impossible to freeze sound because it is in time.” He is in Melbourne for a series of performances and lectures in late August, curated by Liquid Architecture, the Melbourne International Film Festival and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image. Of keen interest to him, as well, is the texture of recorded sound, something he began experimenting with decades before the digital renaissance. As situations, surroundings and perspectives change, so too do the sounds. Listening back to the recording of our conversation, which took place in a busy, and noisy, café in Melbourne, I’m aware of the discordance between experience and recording. Joined by his wife Anne-Marie Marsaguet, we were surrounded by — as Chion might call it — “bruit,” a French descriptor for anything that interferes with our aural receptors, that we don’t necessarily want. (The French language can be more descriptive, he says to me.) Certain sounds are enlarged and others dulled in a distracting litany behind our voices echoing back to my phone’s recording point. In one sense, it’s unpleasant, but there’s much to be gained from a close study of it. I hear a bird chirping loudly somewhere above us, and remember a particular moment, as Chion mentioned Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds and gestured to the sound, smiling.

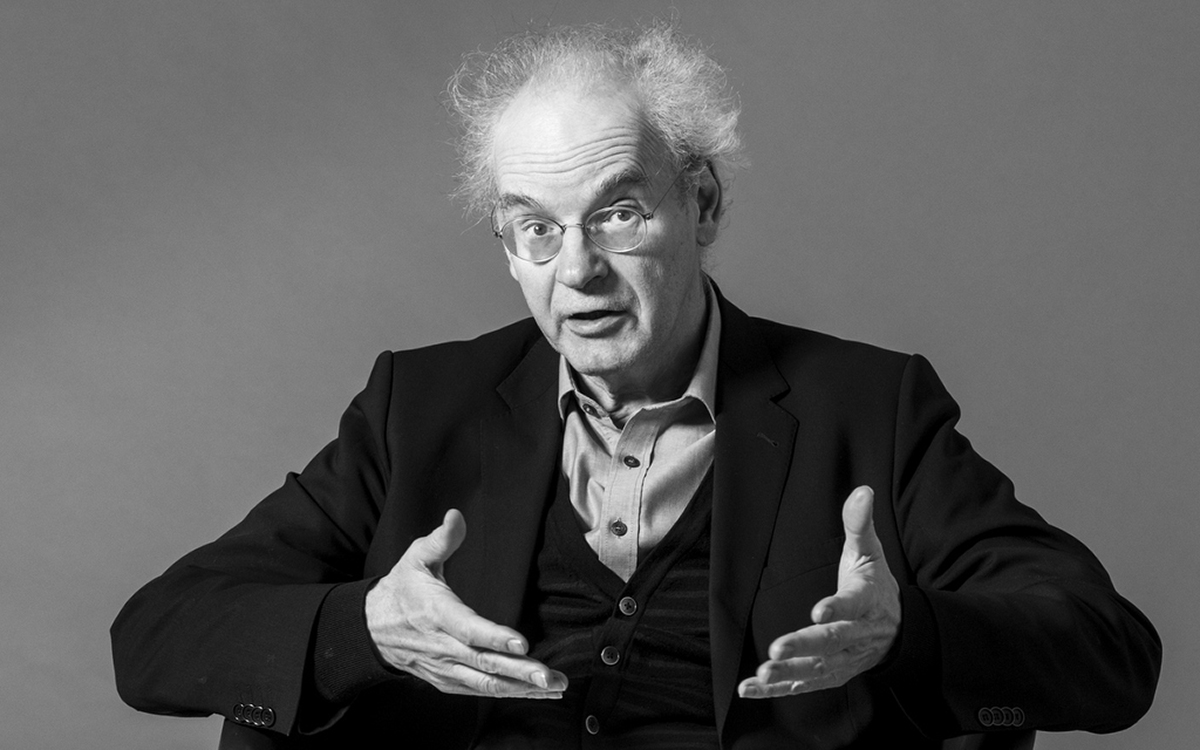

Michel Chion, Joel Stern, photo Keelan O’Hehir

“If I had to describe me, it’s difficult,” says Chion. “I would say that I am a searcher.” He also admits to being a writer of books, an historian and an observer of phenomena. Observing is a neutral term and a multisensory one, not restricted by Western civilisation’s typical ocular bias, but importantly not excluding sight. “I am trying to be a scientist. A scientist of listening,” he says, but later he seems to reconsider this, and rephrases. He is an observational scientist.

For Chion, the experience of seeing and listening together is an essential part of everyday life. And this life experience can be found in the cinema, the world refracted on the silver screen. These experiences are about being attuned to the spaces and sounds in the audiovisual, polyphonic expanse around us. “We cannot, from morning to night, be actively listening. We have to be sensitive [to what’s important].” But it’s a fact, says Chion, that the inner ear redirects itself towards the dynamic sound phenomena around it. A film’s sound, emanating from speakers, only truly takes place when it reaches the ears, something he states in Film: A Sound Art, his book translated into English in 2009 by Claudia Gorbman.

Chion’s performance in Melbourne on 17 August included the world premiere of a work of musique concrète, The Scream, and was followed by his famous Requiem and the 80-minute Third Symphony, the most sensorially dynamic of his three concert pieces that enlarge the visual space of the screen with sound from surrounding speakers. In Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, also translated by Gorbman, he writes, “Cinema is not solely a show of sounds and images; it also generates rhythmic, dynamic, temporal, tactile and kinetic sensations that make use of both the auditory and visual channels.”

His compositions aim to create this kind of cinematic affective sensation, too. By contrasting the meaning of words with images and sounds, he creates a fluid shift between alignment and chasmic disagreement. “What is important for the experience is totality,” he says of these compositions. “You can, with an orchestra, or with a movie, rebuild a soundscape. But it’s completely artificial, made with different sounds, at a different time.” He thinks of his compositions in the same way, as new experiences. “As a composer I define musique concrète as an art of fixed sounds, but fixed sounds are not the recording of precise sounds, pre-existing sounds. They are new objects.”

Michel Chion, Anne-Marie Marsaguet, photo Keelan O’Hehir

The sound of David Lynch

Chion has been a key thinker about these soundscapes for decades and even his older writings remain relevant. With this in mind, I ask about the soundscapes of someone with whom he is very familiar.

“There are extraordinary moments, and it’s very experimental. The most important thing in David Lynch’s case, is that he has a feeling of space and time,” Chion says of Twin Peaks: The Return. “And if you have a feeling of space and time, you can express it with time and image.” He describes the opening scene of Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997) that he uses while teaching, where husband and wife, Fred and Renee (Bill Pullman and Patricia Arquette), engage in slow conversation, with deliberate pauses in their dialogue. For Chion, the scene is an image of eternity. Moments that appreciate time in this way — as a sort of anti-narrative — are becoming extremely rare. “Today on the TV there are no more intervals, because of commercials and with remotes, people change channels. That people keep going to the movies, especially slow movies, is in my opinion to rediscover what is important in an interval. So, even if in David Lynch movies there were no strange situations or no strange sounds, his sense of tempo and space would be very strange, very specific.”

It’s clear that this sense of temporal experience is key for Chion. Throughout our conversation, the concept he returns to the most is not sound but time. Waiting, he says, is an essential part of our existence and we need to appreciate the interval. Slow down and observe the world; he and Marsaguet smile. “To let the cosmos exist.”

–

Melbourne International Film Festival, Michel Chion, The Voice in Cinema, ACMI, 16 Aug; The Audio-Spectator Concert, ACMI, Melbourne, 17 Aug; Presented by Liquid Architecture, Melbourne International Film Festival, ACMI and Institut Français.

Top image credit: Michel Chion, photo courtesy the artist