Slow traumas or apocalypses of choice?

Francis Russell: Inanition: A Speculation On The End of Times

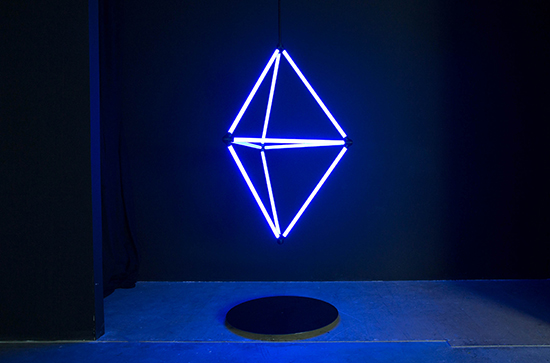

Joshua Webb, Midnight, Inanition

Inanition: A Speculation On The End of Times, curated by Laetitia Wilson at Success Gallery in Fremantle, is an exhibition caught between the now conventional moralism of eco-crisis and a desire for the speculative possibilities afforded by jettisoning our all too human perspective by reaching for something beyond terrestrial morality.

Certainly, the show is refreshing in substituting for ecology the more progressive tropes of science fiction. Unlike recent shows in Perth such as PICA’s Radical Ecologies, which felt conservative in its emphasis on a static conception of nature—animals, insects, humans, organic entropy etc.—Inanition looks beyond such familiar tropes to recast the debate about the crisis of the anthropocene in a speculative guise. Instead of moralising about a nature lost, the works in Inanition seem geared towards the possibility of nature as the unforeseen, manifesting in works that challenge precisely the conservative reception of ecology—ie that organisms have homes.

In particular, Kelly Richardson’s The Last Frontier, which depicts an enormous atmospheric dome pulsating in a barren landscape, and Claire Evans and K.M. Merrill’s OK TO GO, a super-cut of “hyperspace” travel sequences from science fiction films, speak to the radical uncertainty of nature at an ontological level without simply reproducing the visual language of the romantic sublime. Embodying science fiction’s capacity to charm, both works cast aside the natural world of nature documentaries, public service announcements and pastoral imagery in order to invoke the possibility of zones and phenomena that are radically incommensurable with humanist notions of nature.

Kelly Richardson, The Last Frontier, 2013, Inanition

Joshua Webb’s inhuman geometry, structured in glowing LEDs and polycarbonate, shimmers beautifully in the darkly-lit basement space of Success. At the base of Webb’s polygonal sculpture, viewers can see themselves partially reflected, albeit in muted form, and obscured by the glossy obsidian support. What is gestured towards in Richardson, Evans and Merrill’s works is made literal by Webb, insofar as its stark vibrancy suggests natural forms that function to absorb, rather than reflect, the human gaze.

Despite the refreshing speculative character of the individual works presented, the framing of the exhibition by Wilson lingers perhaps too long on the more conventional preoccupations of art that grapples with the anthropocene. Meditations on the “end times,” and the influence of Christian eschatology on such meditations are common in the broader genres of science fiction that Inanition draws on. Classic works such as Arthur C Clarke’s Childhood’s End and the popular anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion are obvious examples of the power of sci-fi re-readings of the end of days. Placed outside a conventional Christian notion of apocalypse, such re-readings are able to avoid a moralistic stranglehold and to approach the question of what it means for beings to exist on a finite planet and in a potentially finite universe. In many ways Inanition’s project feels similar, and the show’s willingness to take seriously the fanciful and imaginative aesthetics of science fiction is refreshing. However, the privileging of the apocalypse as a single event, as something that will actually be encountered at a specific end point of history, is one of the more conservative tropes that Inanition struggles to throw off.

One of the reasons the conventional approach to the notion of the apocalypse is conceptually and aesthetically inhibitive is the manner by which such a notion of the “end of days” fails to deal with the personal apocalypses that are continuing all around us. Our own mortality, and the mortality of those we love, can make the sense of a broader extinction too abstract to really have any powerful impact. I could be wrong, but perhaps the fragility of one’s own life, and the lives of those we care for, hinders our ability to worry about a future apocalypse that will be worse than what many already endure. There is, however, an alternative tradition of approaching the end of days, one that can be found in re-readings of the Christian tradition (see Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s later work) and in Inanition’s stand out work: Erin Coates’s Driving to the Ends of the Earth. In this video work, Coates takes on the role of a Donna Haraway-esque figure, situated in a station wagon replete with a host of non-human kin, like dogs and plants, driving through crumbling landscapes and hellish infernos. In such a work one finds not one traumatic ‘end,’ but rather a host of different ending times, each of which poses different challenges. Such is perhaps the only way to truly affirm the challenges ahead.

Erin Coates, Driving to the Ends of the Earth (HD video still), Inanition

Inanation: A Speculation On The End of Times, curator Laetitia Wilson, artists Thea Constantino, Joshua Webb, Erin Coates, Kelly Richardson, Patrick Bernatchez, Claire Evans, KM Merrell; Success, Fremantle, 4 Sept-2 Oct

RealTime issue #134 Aug-Sept 2016