Space travels

Mireille Juchau

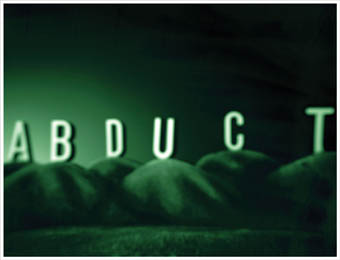

Ronnie Van Hout, Abduct

Narelle Autio’s series of 6 colour photographs, Faith, reveals the dual aspects of her theme—as blind people are led through Sydney streets by their guide dogs, light suddenly illuminates each scene as if uncannily choreographed from above. Autio’s work is part of PhotoTechnica’s She Saw, an exhibition of documentary photography, which contains both recent and older works from well-known and emerging women photographers.

Deep and dark, as if shot at twilight, and full of elongated shadows, the images in Faith contain sharp lines, cones or pinpoints of blazing light, which briefly illuminate the sometimes claustrophobic city settings. These moody cityscapes suggest the shadowed, or completely dark experience of moving through the chaos of the city with no, or limited sight. Some of her subjects, Autio says, can just make out bright casts of sunlight, or feeling the heat of a sudden shaft, will sometimes ask if she took a shot at that moment.

Faith—that the blind invest in the dogs who lead them on their regular routes—is central to these works but so is the examination of public and private space. Guide dogs require a clear box-shape around them to work, which means Autio had to keep well away from her subjects while working, in order not to confuse the dogs who’d grown familiar with her scent. Despite the often crowded settings there is a spaciousness in her composition: footpaths appear like welcome clearings in a crowded grove, train tracks stretch into the distance, suggesting other journeys.

Jackie Ranken photographs places from a great height, and virtually upside down. Ranken’s 8 silver gelatin prints of her home town of Goulburn were made during near-acrobatic manoeuvers in her father’s plane. Prohibited from acrobatic flying above the town, Ranken’s 74 year old dad has perfected the art of tipping his Tiger Moth’s wing to the ground without flipping it so his daughter can capture her evocative shots of the town’s geography. Including both manufactured and natural structures shot from the air, and therefore lacking horizon lines, these Urban Aerial Abstracts take a while to decipher visually. In this sense, like Autio, Ranken prompts us to consider what we take for granted in our ways of seeing, to become aware of how we scan a photograph, assuming we’ll rapidly discover its direct connection to the real.

In Ranken’s work, what looks like a series of boxy houses divided by roads turns out to be a graveyard bisected with paths and then, stepping back, a flag. The circular formations of rose gardens or dams look more like urban forms of crop circle, all their detail miniaturised and made strange; the overlapping roads of the Goulburn bypass become a marvellous spirograph that leads the eye around its curves.

Ranken’s approach lovingly transforms everyday structures into something new. The sweeping lines and textures here remind me of work by some Indigenous artists (Rover Thomas for example) where bold shapes describe features on a 2D landscape. The flatness of Ranken’s style gives the work an appealing abstraction in a show of mostly realist documentary photography.

Moving even further into the stratosphere is Spaced Out at the Australian Centre for Photography. Part of the Sydney Festival, this collection of international and local works examines both real and imagined deep space, space travel and humankind’s continual search for new territory, or life beyond the earth.

In the ACP foyer William Eakin’s series of pigment inkjet prints memorialise the Russian cosmonauts of the early years of space travel. Eakin’s (Canada) series includes space memorabilia—A US Moon Landing Badge and a Japanese collector card featuring cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin. Beside these are several sepia head shots of other Russian cosmonauts; in circular frames they look a little like Russian icon paintings, or faces peering from portholes in antiquated rockets, or from space helmets. These once famous men stare out from black backgrounds pocked with tiny white stars. Eakin’s work reminds us how quickly what was once revolutionary can pass into the frozen zone of kitsch.

Also referencing popular mythologies of space are Ronnie Van Hout’s inket prints in the gallery proper. Each print contains a suitably discomforting concept in the form of white lettering—ABDUCT, UFO, CREATURE, HYBRID—against differing, spookily green landscapes. The word STRANGER appears to melt, morph or pulse before your eyes, and though it’s a trick of the dim gallery light, this animated quality effectively evokes the sci-fi schlock cinema of the 50s which Melbourne-based Van Hout references. While the exhibition notes claim The artist’s work is “less about outer space than the caricaturing and dramatising of cold war insecurities” the oversized white lettering and the hilly backdrops in his MONSTER shot also suggest the mythical land where such films were created, reminding me of the HOLLYWOOD hills where silicon enhancement and Botox are spawning new forms of life but not as we know it.

Juxtaposed against David Malin’s astronomical imaging, South Australian Holly Wilson’s fabricated galaxies and starbursts look remarkably convincing. Reminding us that our fantasies of space are often at least visually linked to reality, Wilson conjures the pocked, rough, corroded surface of a blue planet, the white explosion of a starbirth, by manipulating chemicals on pieces of film.

I find I can only make sense of photographic scientist Malin’s brightly coloured images by imagining them as something closer to home. They make me think of our own deep spaces. A brightly coloured swirling galactic mass looks like something protozoic, something possibly internal; a crimson webby expanse appears more like the surface of the womb shot with a surgical camera than anything out there.

Russian Yuri Batourin turns the camera back to earth from space, revealing the blue curve of our planet, the white-flecked oceans that cover most of its surface. Cited in the notes as a “21st century version of snaps from the plane, the hotel, the conference centre,” Batourin’s work captures the kind of views most of us will never witness. However, a quick search on the Internet reveals that for the wealthy, space travel is now a possibility. For a mere $US20 million (plus 6-months to a year of training, possible nausea while aboard and backaches after landing) you can spend 8-days in the International Space Centre and souvenir your own shot from beyond our universe. Spaced Out makes me wonder how soon it will be before the moon, now colonised, photographed and souvenired; mapped, charted and traversed becomes simply another (expensive) suburb of Earth.

She Saw. Australian Women Documentary Photographers, curated by Karra Rees, Photo Technica, Chippendale, Jan 18-Feb 15

Spaced Out, curators Alasdair Foster & Reuben Keehan, Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney Festival, Paddington, Jan 10-Feb 1

RealTime issue #53 Feb-March 2003 pg. 30