Speechless: Giving voice to refugees

Few operas are written in Australia and even fewer are publicly workshopped as part of the development process. Cat Hope, Professor of Music at Monash University, and Head of the Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music, is developing a major new operatic work, titled Speechless. The audience response to the opera’s first outing over two nights as part of Adelaide’s Vitalstatistix incubation program was overwhelmingly positive.

Hope describes Speechless as “an experimental noise opera — in three acts, for four soloists, the Australian Bass Orchestra and choir.” Distressed at the inadequacy of the response to Gillian Triggs’ 2014 Human Rights Commission report, The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, Hope based the graphic score and thematic material for Speechless on elements of the report.

This intense and dramatic work of roughly an hour’s duration involves four outstanding soloists — Alice Hui-Sheng Chang, Kusum Normoyle, Judith Dodsworth and Sage Pbbbt — with two Adelaide community choirs, Hoi Polloi and Born on Monday, and the Australian Bass Orchestra (formed by Hope in 2014) playing cellos, double basses, bass guitars, bass brass (trombones, tuba and euphonium), bass drums, electronics (including a theremin), and a harp, all held together by conductor Aaron Wyatt. While the orchestra all play below middle C, the choir and soloists extend into the upper registers, creating a dialogue across the treble and bass staves that suggests children being tossed around on stormy seas. In other contexts, this might be considered experimental music, that is, music intended to explore sonic or instrumental possibilities. Importantly, there is no dialogue in the opera. The extensive range of vocal sounds, from hissing and muttering to screaming, do not convey speech, reflecting the opera’s title. Hope’s intention is to convey the silencing of protests against detention, and the opera is thus both a personal statement and a highly successful musical innovation.

I spoke with Cat Hope about the workshop performances of Speechless.

Cat Hope and score for Speechless workshop, photo courtesy Tura New Music

Your program note makes clear how the situation of children in detention has inspired the opera, but that you did not want to be didactic. The resulting work is emotionally intense without being so. How well do you think it worked in expressing your concerns?

The opera is about my concern for people who have been rendered speechless by decisions made by the Australian government: refugees, children (as refugees from domestic violence) and Indigenous communities. I was aware that any attempt to communicate this was a big risk — how to make a work on a very specialised topic without any narrative, words or action, and not be programmatic? Are the tools of my music enough? And, is the intent communicated or is it all too abstract? I think that once the context is provided (through the program note, for example) people find their own connections, their own narratives and meanings. It can be different for each listener, no one is being told how to feel or react. The work is driven by my response to important issues of our time. The singers need to find meaning in it for themselves. I think we succeeded in that performers and audience alike found that meaning.

Speechless is a large-scale work that combines a unique ensemble — a bass orchestra — with community choirs, soloists using extended vocal techniques and graphic scores. It already seems highly resolved, but having seen it in performance, how do you now feel about it musically?

I came to the workshop process with 50 of the 55 minutes we presented written, then added a new interlude, and made some significant changes once I got there. I had engaged many operatic devices and plotted the structure out quite carefully. But I have worked with the Australian Bass Orchestra, and low frequency instruments more generally; I knew more or less what to expect. I chose my collaborators carefully, and made sure that there were people leading sections who know my music, who understood it and, when required, could bring their own style to the piece. It was a very moving moment, one that I will never forget. There are still some changes I would like to make that will take longer than we had between rehearsals.

What was the impetus for the creation of the Australian Bass Orchestra and why did you incorporate a pre-existing musical concept into Speechless?

I formed it to perform low frequency music that was not driven by any style or instrument plan and could be formed in any place with any players of any instrument with a bass range. It is a sporadic project that only occurs when an opportunity arises. I thought a lot about how to handle the complex topic of the opera, and realised the concept of the bass orchestra would suit. As with the engagement of the community choir, it was important to me that the work speaks from, as well as in, the place it is performed. Local performers bring that. Given how important it was for me to not speak on behalf of anyone, it seemed the right place for an orchestra like this to be engaged.

Cat Hope with conductor Aaron Wyatt and soloists Alice Hui-Sheng Chang and Kusum Normoyle, Speechless Workshop, photo courtesy Tura New Music

Were the soloists selected to introduce their individual vocal techniques into the overall composition? Is there flexibility in the score to enable performance with other soloists?

It was important that the singers each came with their own style, and their parts reflect different qualities they bring — not them personally, rather their approach to music. The soloists coming from an improvisatory practice have more freedom; Kusum Normoyle has her own “scream” part, while the operatic soloist, Judith Dodsworth, has a poignant “aria” moment. I have thought a lot about what makes this work an opera, and how opera reflects issues and music of the day. Music of the day is a varied and complex thing: pop music, improvisation, classical, jazz, sound art and so on… So I chose the four singers from this pool of contemporary practice, and my score enables them to interpret it from within their own realm of experience.

You have considerable experience in the use and development of graphic scores. Are they effective in encouraging the performers to extend themselves and to be active interpreters of the material?

Graphic notation has enabled my compositional practice for a couple of reasons. It’s the best way for scoring the elements core to my composition: drone, glissandi, texture, aleatoricism and the absence of pulse. Its openness can remove implication of style, another thing that is important in all my music. You know how jazz charts often use a special “jazz font”? You almost have to play it differently when you see that. Most music is not notated at all these days. This kind of graphic notation — coordinated and carefully plotted — can be followed by any musician. As you say, it enables active interpretation, which is key to the theme of the work. But you need a musician’s skills to get the best out of it. I am particularly excited about how well our Decibel ScorePlayer iPad application, the mechanism we used to deliver the score to the performers, managed with such a large, spread-out group. Everyone had their own part, but could still see the others, and the score was controlled and led by the conductor. There were even lighting and audio cues in the score. We really pushed the graphic notation copying and typesetting process during the development period, and by the end, we had real time edits going on as the orchestra was playing the score, ready for the next day’s rehearsal.

Including local choirs engages the community, as does your Speechless blog in which you reflect on the process of development. Is this broader strategy of engagement valuable in reinforcing the opera’s message for the public?

Jeff Khan, Artistic Director of Performance Space, mentioned after the performance that the presence of a choir made it seem like a “citizens’ address,” which I think frames it perfectly. Community choirs are often formed for reasons other than musical interest, and more for wellbeing and bringing people together. I found these choirs to be more open-minded about experimentation and extended techniques than a formal choral group singing, say, The Messiah. They wanted to empower themselves somehow, to communicate about this issue of the lack of voice. Some came from troubled circumstances and the project really offered them something.

Speechless workshop, photo courtesy Tura New Music

Presenting a work like this involves coordinating and supporting large numbers of performers, crew and venue staff. How important is it to have organisations like Tura New Music and Vitalstatistix to provide a platform for public workshopping?

I was very fortunate to have them partner this workshop period. As you probably know, most operas come to life with the composer holing up and writing the work, then the performance being locked in after with a very short rehearsal period. In this case, we were fortunate to have just under two weeks to try things. I only had the full orchestra for four rehearsals, but I was able to work with the choir, the soloists and the orchestral leaders — Tristen Parr, strings; Aviva Endean, winds; Tina Havelock Stevens, percussion; and Stuart James, electronics and everything else — leading up to and in between the big rehearsals. This was important as it gave everyone time to process what for many was pretty out there new material and a different way of working. The Vitalstatistix venue was perfect for this; they made us feel very welcome, and Tura kept everything running smoothly. I am very pleased with the way it worked out, and can’t wait to see and hear a fully staged production.

–

Speechless, composer, director Cat Hope, for Australian Bass Orchestra, choir, vocal soloists, producer Tura New Music, development partner Vitalstatistix, 2017 Incubator Residency Program.

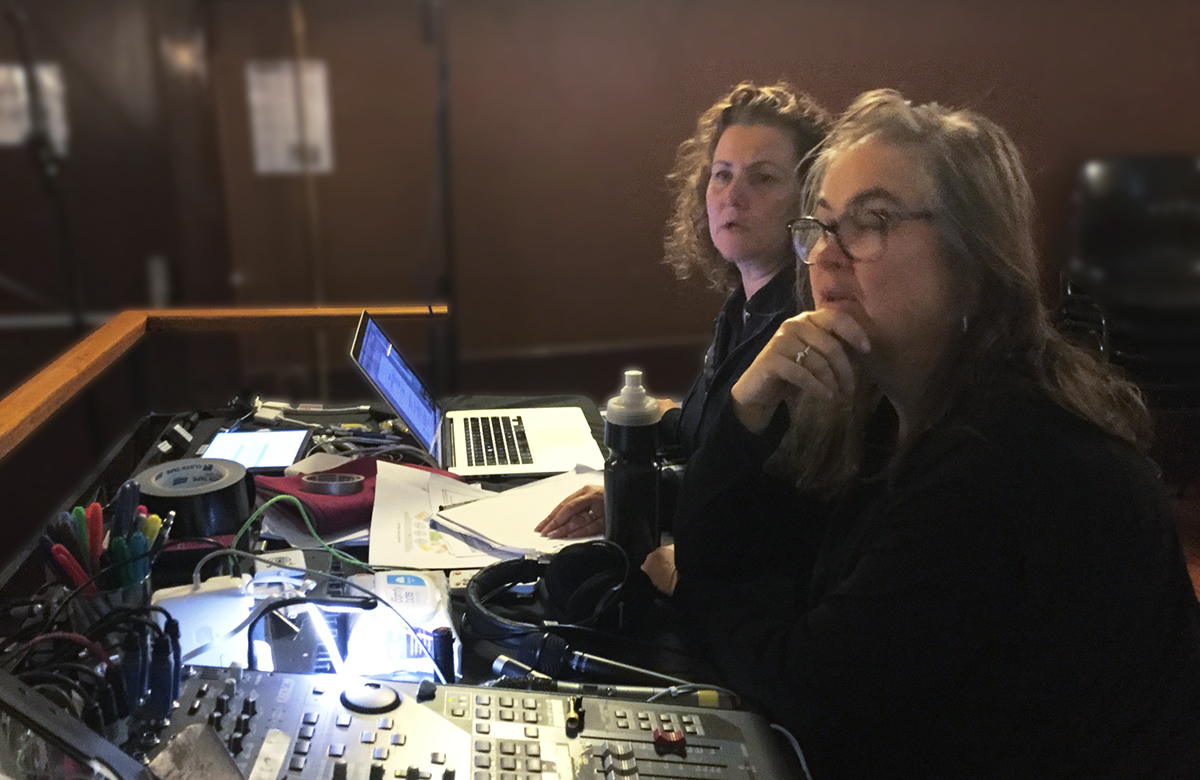

Top image credit: Cat Hope and Susan Studham (stage manager) at production desk, Speechless workshop, photo Deborah May