Strategies for a theatre at risk & in decay

Richard Murphet: Theatre @ Risk, Theatre in Decay

Theatre@risk

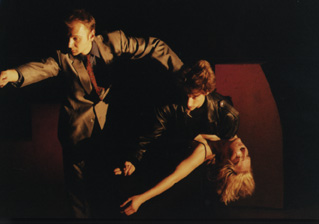

photo Kirrilly Brentnall

Theatre@risk

I don’t know any other way apart from convincing people to work with you and getting some work under way, even unpaid, and presenting it to any public—in a cellar, in the back room of a pub, in a hospital ward, in a prison. The energy produced by working is more important than anything else. So don’t let anything stop you from being active, even in the most primitive conditions, rather than wasting time looking for something in better conditions that might not come off. In the end, work attracts work.

So said Peter Brook, trying to answer an enquiry from a hopeful young theatre director.

The problem has always been the same. How to get started, how to continue, how to establish yourself in order to earn a living as an artist whilst not compromising the vision that got you going in the first place. These days, however, the competition is stiff from other media, money is scarce and it is much harder to live on the breadline.

Theatre itself is seriously under threat. The mainstream struggles along with an aging audience and does what it can to attract a younger one, while the non-mainstream has shattered into a thousand directions—all productive, many of them opening up kinds of performance work which would not have been seen in previous generations, but at the same time shattering the audience base and presenting young theatre artists with serious questions of identity in relation to the work they are doing.

Two new theatre companies in Melbourne provide fascinating alternatives to ‘getting some work under way.’ In their names, Theatre @ Risk and Theatre in Decay both directly face the dilemma of the artform. Robert Reid, the founder, writer and director of Theatre In Decay remembered, “When we started in 2000 all I could hear anywhere is that ‘theatre is in decay’ and I felt that I couldn’t work in this industry without acknowledging upfront that is how we are being seen—so what to do about it?” Chris Bendall of Theatre @ Risk admitted that “naming it was tongue in cheek in that we knew we were going into risk in doing it” but asserted, too, that for him and Victor Bizzotto, directors of the company, the only way to save theatre was by taking risks and by challenging their audience to take them—”to go to a deeper level.”

Theatre @ Risk began this year with an ambitious season of works at the recently opened Blackbox Theatre at the Victorian Arts Centre. The first production was a double bill of the thriller, Polygraph, by the French Canadian writer Robert Lepage and the celebration of cultural miscegenation, The B File, by British writer Deborah Levy. Their second production was Louis Nowra’s urban nightmare The Jungle. They were to mount Austrian writer Thomas Bernard’s Histrionics in December until financial considerations caused them to postpone until next year, when they also plan to present a new play by Chilean, Ariel Dorfman, and to develop a show of multi-languages and voices based on the concept of the Tower of Babel. A key focus for the company is what Bendall describes as “trying to find some meeting point between difference, a collision of languages and cultures.”

On an immediate level, this is to do with an interest in performing shows from around the world that would otherwise not be seen in Melbourne, but it was evident too in the collisions between class, gender, race and occupation in The Jungle—the urban chaos of subcultures. The form the company prefers is one that moves fast between various locations and times, a mixture of strong text with bold physical images, judicious use of music and “a pumped up fast and driving techno energy—abrasiveness and rawness.” It is a theatre for a new breed of educated young theatregoer.

The aim nevertheless is to provide an alternative to mainstream theatre from within the body of the beast. The choice of Blackbox as a venue provides a home right in the heart of the Arts Centre. The texts are ones overlooked by other theatre companies but they are recognisable as theatre texts. The shows get reviewed by mainstream as well as alternative press (Helen Thomson of The Age is particularly supportive). Their aim is to develop the company to the point where it can attract government funding. They are in for the long haul. Their productions are minimal and stripped back but they are stylish and as such demand more cost than the still-growing audience numbers can cover. That is their dilemma. All the work so far has been donated free of charge by artists and crew involved. And the directors have outstanding debts to pay. They set themselves this year to get a following and a name. This they have achieved but it has been at enormous cost, physically and financially. For Bizzotto, in his early 40s, the challenge is a critical one:

There is a part of me which wants to continue to be the independent artist out there being invigorated by the challenge and this other part where I get home and it smacks me in the face—it actually frightens me—I have to support my family and I don’t know how I am going to do that.

Robert Reid’s Theatre in Decay is on another path altogether. Since he founded the company in 2000 they have produced 10 plays, nearly all written by Reid and all directed by him. The plays are of various lengths, some monologues, some dialogue, and some grouped together into longer combinations. They play at various venues around the city: fringe theatres, pubs, on the street. The aim is to get stuff out, as much of it as possible and as often as is humanly feasible. It’s like a guerilla theatre—short plays, coming from unexpected angles, happening in different places, in different contexts, about different issues, in different genres—no sense of building up continuity, more a sense of trying to break continuity. When I asked Reid whether the name of the company suggested that they were trying to rescue theatre or to destroy what we have known as theatre, he nodded in amused understanding and quoted Geoffrey Milne’s comment on the company on the ABC: “one wonders whether they are the solution or the problem.” He admitted, “I’m less and less interested in theatre as an idea.” His focus is fully on the relationship of the audience to the performance.

What isn’t being addressed in most theatre that I go to is audience inclusion; everything feels in the same setup—audience/ stalls/darkness/stage/actors/light—audience sit face front, rank-and-file and are expected to not talk not cough not laugh too loudly, in essence pretend we don’t exist, we exist in our own imaginal worlds and any intrusion from outside interrupts it and breaks it—‘the magic of theatre’. It feels to me like that is a brittle, fragile type of theatre, alienating audiences, because people would much rather be a part of an art event than just witness to one. Very often the work of ours that gets the best response is that where the people can move around, talk to their friends, drink, eat, sing along.

In TID actors pretend to be nothing other than actors and to be nowhere other than where they are: ‘‘What you see is what you see; if the actors aren’t pretending to be someone else and somewhere else the audience doesn’t have to pretend to be no-one and nowhere.” The genre that the company prefers to work in feeds that sense of audience stimulation and inclusion—horror, schlock-horror—because “I enjoy it and actors enjoy it and audiences enjoy it and I don’t see it done on stage often coz it’s very difficult to do horror properly.” He cites an example: “All the Damned Zombies culminated in a scene where 14 actors in a pub each grabbed an audience member and ground their crotches into the audience member’s head with confetti flying everywhere and the sound guy picked up a live chainsaw and ran through. Every single night at the end of the scene people burst into applause; it released something deep in them.” This sense of deeper release is another motive for the choice of genre: “what makes it scary is the constant reminder that humans are fragile—a reminder of our own mortality.”

The focus is also on the politics of human interaction: “the stuff I do as a writer is either horror or politics; more often these days both at the same time. New Scum dealt with sweatshop labour and the attitude of the public towards drug use and addicts. The Girl Who Lived in the Coke Sign Above St Kilda Road was a monologue about homelessness and escaping from homelessness but ending up in advertising.”

Unlike Bendall and Bizzotto’s thoroughgoing vision for the future of their company, Reid is far more circumspect: “I don’t know if TID is the kind of company that gets funding—it’s less important for me to have the funding, partially because I believe that if we can buy our way out of a situation we don’t have to think our way out. I think that TID has a relatively short shelf-life and once it has run its length it will evolve into something else.” In his case, the ‘something else’ is 2 plays to be performed by Australian Theatre for Young People, the possibility of a commission from Playbox and works commissioned for The Storeroom.

While Theatre @ Risk are on the lookout around the world for new images, fresh voices, and working tenaciously to keep their vision alive, Robert Reid sits at his job at Telstra with pen and paper at the ready and listens to the wild voices in his head.

Theatre @ Risk: Chris Bendall & Victor Bizzotto (artistic directors), Kirrilly Brentnall (company manager), Amanda Silk, Rob Irwin & Nick Merrylees (design team) and a loose ensemble of actors.

Theatre In Decay: Robert Reid (writer/director), Anniene Stockton (manager) and a loose company of performers including Telia Nevile, Elliot Summers & Robert Reid. Their current play is All Dressed Up and No-one to Blow, 27-31 Munster Tce, Nth Melbourne, September 25-October 13

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. 36