Supersense: Ecstasy sought, partly met

Three guitars are held aloft, one played by the musician’s tongue, and all of them are blasting out Acid Mothers Temple’s euphoric brand of psychedelia. It’s the kind of blistering sonic lather that is rarely encountered at 6pm on the stage of Melbourne’s State Theatre. But tonight, and for a majority of Supersense’s “festival of the ecstatic,” the theatre and the Arts Centre that houses it, are doing their best to portray a different kind of space — one that is transformed and transformative.

Audiences descend into the belly of the Arts Centre via stairwells and passageways that gurgle and heave with a soundscape that anthropomorphises the building, suggesting digestion. Yet what is being absorbed, and by whom or what, is a question that arises repeatedly over the festival’s weekend.

Memory Field

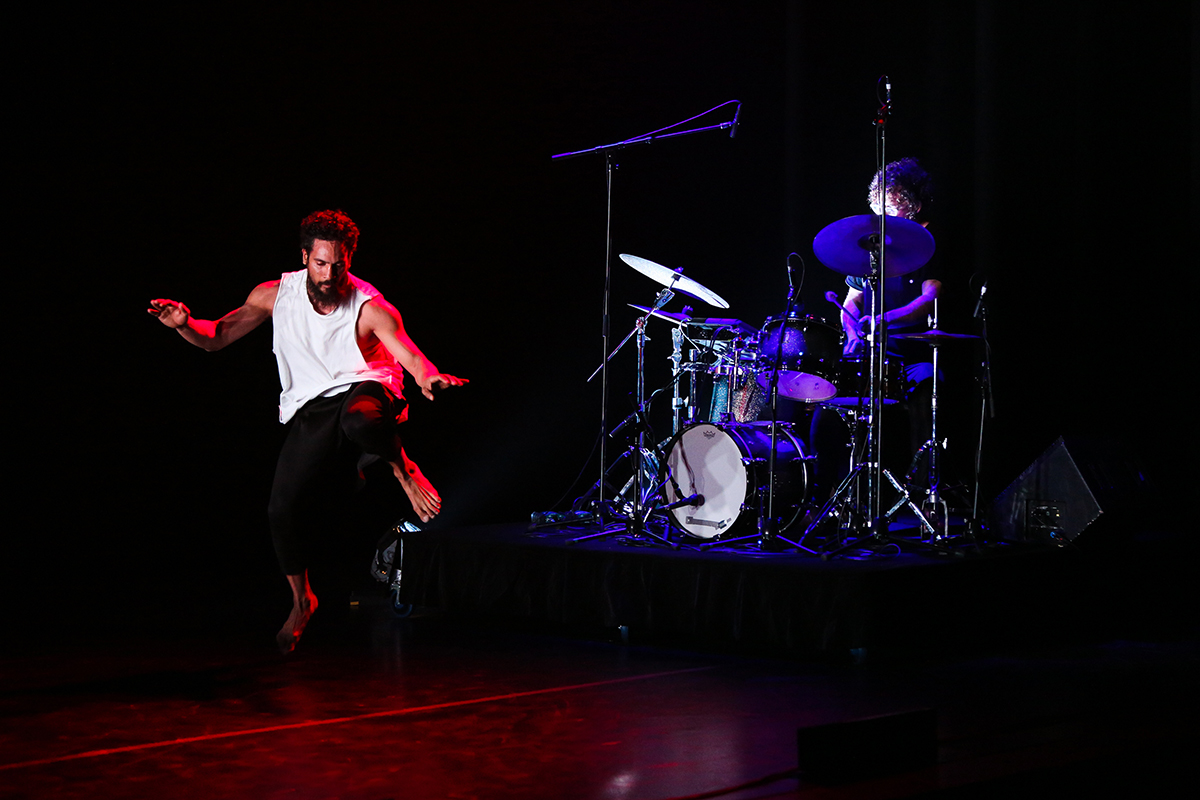

A thematic concern with dream, memory, the alien and otherworldly pervades the Supersense program. Amid these, and perhaps despite its name, Memory Field feels very present. A duet between Bangarra dancer Waangenga Blanco and PVT drummer Laurence Pike, Memory Field begins in a haze of static and a pool of light. The stage is divided in two, Blanco caught in the spotlight on one side, Pike sculpting the soundscape from behind his drum kit on the other.

Blanco incorporates elements of traditional movement from the Torres Strait in his choreography. This vocabulary is woven through the tormented lyrical style, as the dancer makes angular contact with the floor to crawl, roll and claw his way around the perimeter of the light’s broad circle. Over the course of the performance, his charting of the light’s limits turns its initial enquiring focus outwards, the movement actively labouring beneath the weight of increasing distress.

Blanco’s circular journey is met beat for move by Pike’s restless score, which teeters, staggers and shudders through the Playhouse. As the circle, or memory field, finally tightens around Blanco’s writhing body, a tightness takes hold of Pike’s obstinate patter, uniting the performance elements in a claustrophobic embrace.

The way in which the artists sustain this seamless tension gives the piece’s exploration of memory (perhaps of ancestral culture) an ominous quality. This in turn reflects the oppressive cyclicality embedded in the act of remembering when the past itself is unforgettable. In a way that is uncommon throughout much of the festival program, Memory Field thus refuses transcendence. Instead it sets past and present in a deadlock, and holds the audience at this impasse, in a manner both challenging and memorable.

Lullaby Movement, Sophia Brous with Leo Abrahams and David Coulter, Supersense, photo Mark Gambino

The Dream Machine

Touted as “the world’s first work of art you look at with your eyes closed,” The Dream Machine seems to come with the implicit promise of upending artistic convention. Conceived in the 1960s by Ian Sommerville, Brion Gysin and William S Burroughs, the work was originally intended to transport the participant into the phantasmagorical, using a record player and flickering light.

For Supersense’s reimagining of the work, an ensemble of artists from across the program, including guitarist Dave Harrington, saxophonist Arrington de Dionysio, harpist Zeena Parkins and the festival’s curator Sophia Brous, have been assembled to provide a live soundtrack for mass delirium. The audience is sprawled across the stage of the State Theatre, eyes closed, when the strobing begins. The music crests and light explodes across the hallucinatory field behind my eyelids. Hot shades of orange and pink burst and blur, following the blazing pace and squeal of Dionysio’s saxophone veering across the multi-instrumental clamour. I surrender to the tide of colour and sound, slightly nauseated, but mostly thrilled.

We are given brief respite when Parkins and cellist Oliver Coates perform an interlude that is striking for the sudden sparsity that is felt sonically and visually. This transitory lull achieves a sense of subtlety otherwise lacking in the performance. For while The Dream Machine’s hallucinatory powers are novel, its dynamics feel less innovative, the score relying heavily on two distinct peaks that intensify the visions one sees while listening. These render the work somewhat predictable, with the audience anticipating the return. That said, as I open my eyes to the sound of Brous muttering poetry, her breath catching on the edges of the score as it winds down, reality feels just a little too sharply focused, suspending a desire to keep dreaming in its wake.

The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane, Supersense, photo Mark Gambino

The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane

We return on Saturday night for a different kind of transcendent experience. Again, we sit on the State Theatre’s stage, but this time the aesthetics of ecstatic intimacy are challenged by the numbers in attendance. The space’s transformation into a long hall hemmed in by white curtains forces disgruntled patrons to spill out beyond the peripheries of the space.

The overcrowding is mostly forgotten as the Sai Anantam singers vividly animate the legacy of Alice Coltrane, musician and founder of the ashram from which they’ve travelled. During the performance, transitions from prayers on high to deep, gospel grooves occur repeatedly, each time drawing the listener a little closer to a conception of the divine that intertwines the cosmically vast with the exquisitely personal. This feeling of totality is encapsulated in the breadth that the synthesiser’s ascending glissando lends to chants of victory, peace and bliss.

However, the Arts Centre’s limitations continually impede inclusivity. Invitations are extended for the audience to make use of the songbooks they are handed on entry and the performers’ sound levels turned down to allow the voices of the audiences to fill out the arrangements. But by design, the space favours loud, grandiose and amplified sound, muffling audience input. Consequently, when a handful of people do take up the invitation to sing, their unamplified voices fail to rise up in elation as they would, one assumes, in Coltrane’s ashram.

Arts centres like Melbourne’s only function efficiently when their Western, metropolitan bias is the default setting. A festival like Supersense directly and indirectly problematises this notion, as its access-all-areas approach denies the space any claim to passivity. Yet in such an initiative, the most effective interventions tend to be ones in which the performers instigate subversion, while the arts centre plays itself. Where an artist like Keiji Haino benefits from being able to pump his screeching sonic miasma into every acoustically submissive corner of the Playhouse, the songs of Alice Coltrane are lost in the ungainly process of imitation that the space undergoes in trying to create context for work that sits outside of its cultural ambit.

In this way, it’s unfortunate that the crowd seemed resistant to joining the Sai Anantam singers in song, but it’s also unsurprising. One doesn’t enter a spiritual state of ecstasy through a side door or the back stage. Such a reaction relies on more than externalities. It must originate, primarily from within.

Deborah Kayser, Peter Knight, Matthias Schack-Arnott, Overground program, Supersense 2017, photo Mark Gambino

Overground

This is perhaps why Overground, the “festival within a festival,” most closely resembles something of the ecstatic. Featuring performers from inside and outside the main program in an afternoon of collaborative improvised works, the festival transpires in the Arts Centre’s foyers. In these spaces, encounters between artists and works may be accidental and ephemeral, the results unexpected and electrifying.

Such is the case in an hypnotic collaboration between Deborah Kayser, Peter Knight, Matthias Schack-Arnott and Cleek Schrey. Schrey, who on Friday night had conjured the falling walls of biblical Jericho through the refrains of Appalachian folk song, here seems to use his instrument to summon the demonic. The tortured whining and sighing he elicits from his hardanger fiddle urges on Kayser’s wraithlike moans, so that for a time, the scene wavers on the brink of becoming a séance.

Curated in collaboration with The NOW Now and Liquid Architecture, Overground eschews assimilation of any one element into another. Instead, it instigates fluid, responsive exchange between the artists, the audience and the site’s specifics. In doing so, the pretensions of the Arts Centre and its audience are dispersed, opening both up to the possibility of rapture.

–

Supersense, Festival of the Ecstatic, curator Sophia Brous; Arts Centre, Melbourne, 18-20 Aug

Top image credit: Memory Field, Waangenga Blanco, Laurence Pike, Supersense, photo Mark Gambino